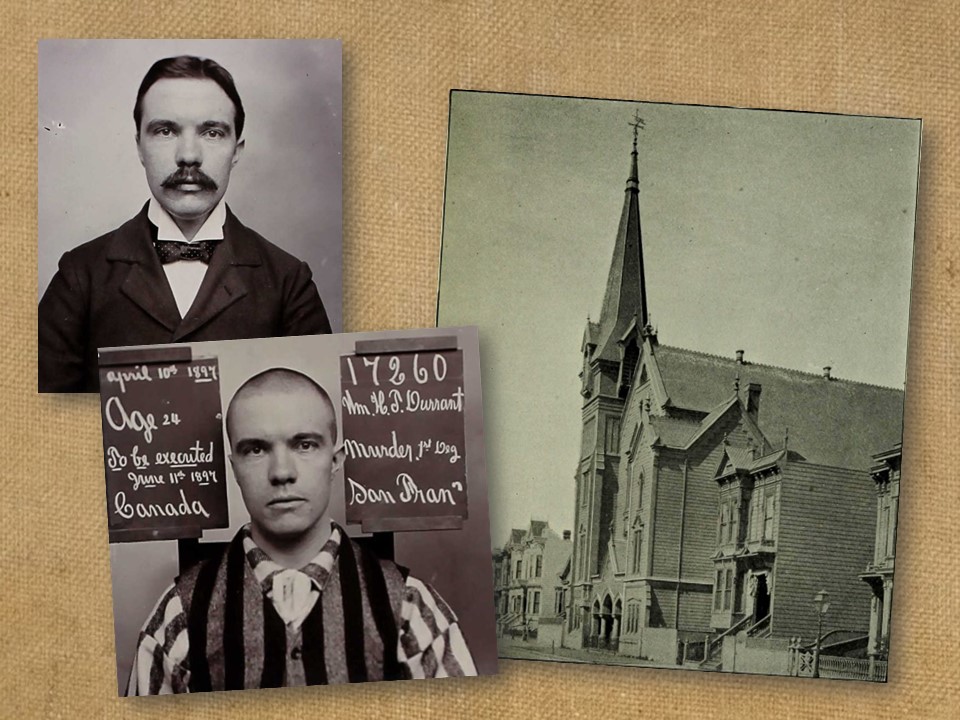

When Theodore Durrant was sentenced to death for murdering two women, an early filmmaker requested permission to film inside the prison. The year was 1897.

The film was intended to raise funds for Durrant’s defense, a scheme concocted by his parents. The family charged admission for this early film, using the money to pay his defense team when his appeal was before the United States Supreme Court.

Dubbed “Demon of the Belfry,” Durrant was convicted of killing two young women in 1895, hiding one body in a church belfry and the other in a closet.

His trial went on for years, garnering headlines and multiple pages of coverage.

(See current filming regulations.)

Durrant’s murder victims

By all appearances, 23-year-old Theodore Durrant was an upstanding young man. Serving in the California Signal Corps, he also ran Sunday school at San Francisco’s Emanuel Baptist Church, all while studying to be a doctor at Cooper Medical College.

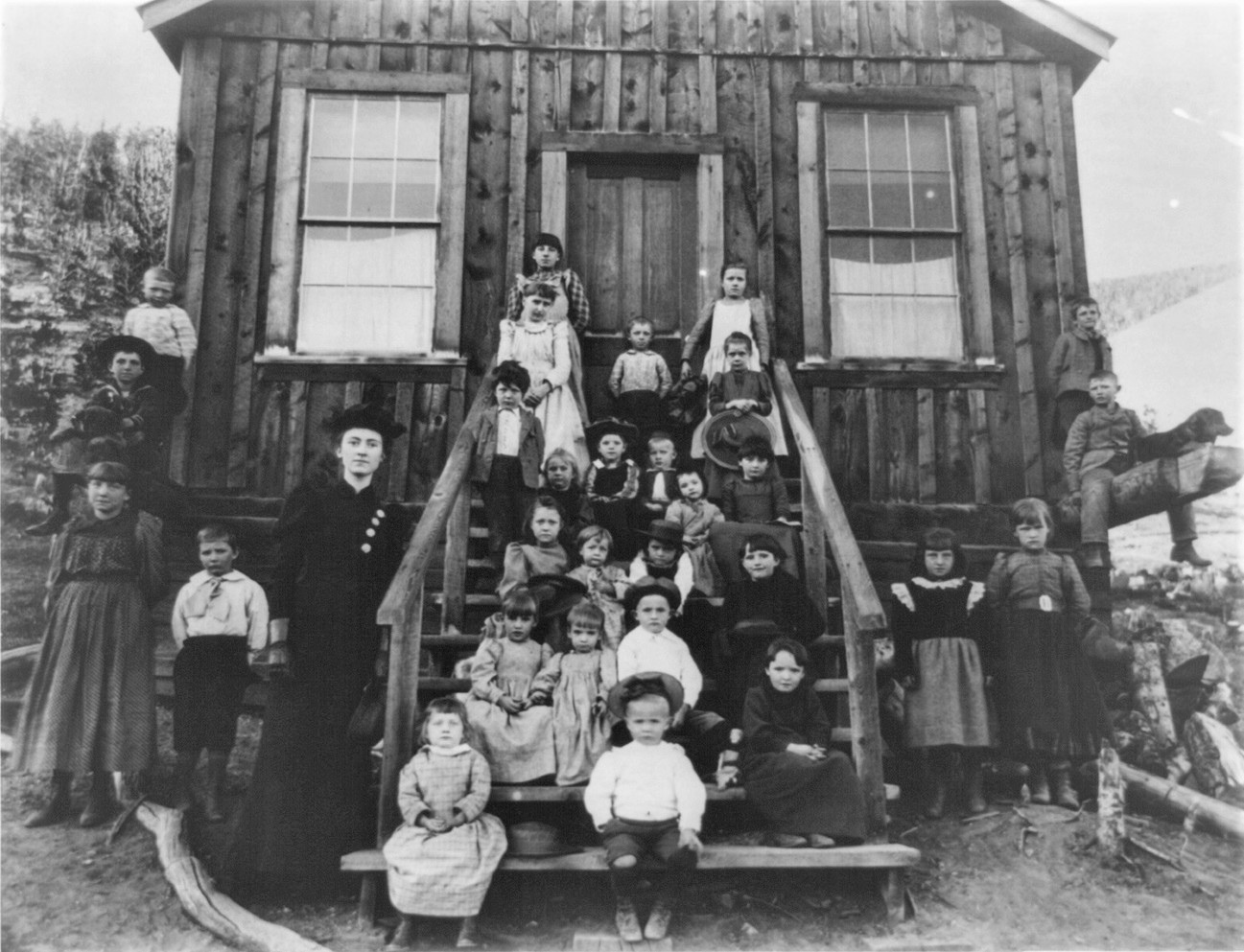

Blanche Lamont, 22, was a recent arrival to California, moving from Montana where she had been a teacher. Her family sent her to live with an aunt, hoping California’s milder climate would improve her health. To better her chances of employment, Lamont took courses at a boys school, a rare achievement at the time.

On April 3, 1895, Lamont left home to attend school. She did not return.

Police began searching while notices were published in regional newspapers, but her trail ran cold.

Nearly two weeks later, as Emanuel Baptist Church began preparing for Easter services, a young woman’s body was discovered in a closet.

“They were horrified to discover the body of a young girl, subsequently identified as the body of 21-year-old Minnie Williams,” according to an 1899 report on the trial.

Church members knew Lamont and Williams. The two were friends who also attended the church.

This link was crucial to solving Lamont’s disappearance, sparking a search of the entire church building. When investigators reached the belfry, they found the door lock jammed, but still gained entry. What they found was shocking.

Inside was Lamont’s nude body, arms folded across her chest and her head steadied by wooden blocks.

Durrant linked to murders

Durrant was also known to be friends with both women. Recently, Durrant made an “improper” advance on Williams, who then reported the incident to her employer.

Williams, a small woman, was employed as a live-in helper for a wealthy merchant’s wife in Alameda.

Both Lamont and Williams were strangled and raped.

According to testimony from a medical instructor, Lamont’s body was positioned as a medical cadaver. Using wooden blocks steadied her head while also slowing decay.

Aside from strangulation, Williams was also attacked with a knife, stabbed a half-dozen times. Additional evidence included her purse turning up inside Durrant’s home.

Despite such evidence, Durrant wasn’t tried for murdering Williams. Prosecutors believed the Lamont evidence was much stronger.

While the trial lasted weeks, it took the jury a mere 20 minutes to reach a unanimous guilty verdict.

After repeated appeals, and an argument before the US Supreme Court, in 1897 Judge Bahrs sentenced Durrant to hang.

Durrant film serves as defense fundraiser

“(Those with) morbid curiosity will soon be given an opportunity of seeing Theodore Durrant through the medium of (film). A few days ago permission was asked of the Warden at San Quentin to take Durrant’s picture. There is a rule at the prison forbidding visitors bringing (cameras) inside the walls,” reported the San Francisco Call, July 8, 1897. “To overcome this difficulty, (they needed) a special order from the Prison Directors. This was done, and Durrant’s father and (camera) operator presented themselves at San Quentin.

“Durrant rehearsed his part in the morning’s drama and the whole affair was over in a short time. Most of the (film showed) animated scenes, and Durrant appears in a variety of attitudes. The films will be sent east to be developed and within a month, the pictures will be ready for exhibition. Great secrecy has been maintained by all (involved) parties and it is doubtful prison officials were aware of the full intentions of the (filmmakers).”

According to one author, the new technology meant the Durrants could reach a wider audience to advocate their son’s case.

“The Durrants used yet more modern technology to propagate their message. (Theodore Durrant) invited the owners of (film camera) to record him picking flowers in the prison garden, raising the blooms to sniff delicately, presumably in an effort to convince viewers that he was a sensitive young man incapable of horrible murder,” according to Philip Hoare’s book, “Oscar Wilde’s Last Stand: Decadence, Conspiracy and the Most Outrageous Trial of the Century.”

The Durrant film was shown in San Francisco, with word quickly reaching the prison that the project was not what officials expected.

Warden takes issue with film

“Warden Hale angry,” read the headline of the San Francisco Call, Dec. 17, 1897. The warden’s daughter could be seen in the film.

“In the animato-scope exhibition on Market street there is a picture of Durrant entering the gate at San Quentin. Several reporters are in the picture and also the Warden’s daughter Sadie.”

The warden, after hearing his daughter could be spotted in the movie, threatened to shut down the theater by lawsuit if necessary.

“A friend who saw the picture notified the Warden, and yesterday afternoon he came to the city. He went straight to the exhibition, paid his 10 cents, and was soon convinced that his friend was correct,” the paper reported. “After the close of the exhibition he explained who he was, (demanding) management (cease the exhibition) in the future. This was refused, and he left threatening to apply to the courts for a writ of injunction.”

The Durrant appeals didn’t work. San Quentin Deputy Warden Amos Lunt, the hangman, carried out the sentence, executing Durrant at 10:37 a.m., January 7, 1898.

There are no known copies of the Durrant film.

As for the church with its infamous belfry, the 1906 earthquake severely damaged the building. It was demolished.

Durrant’s famous sister Maud Allan

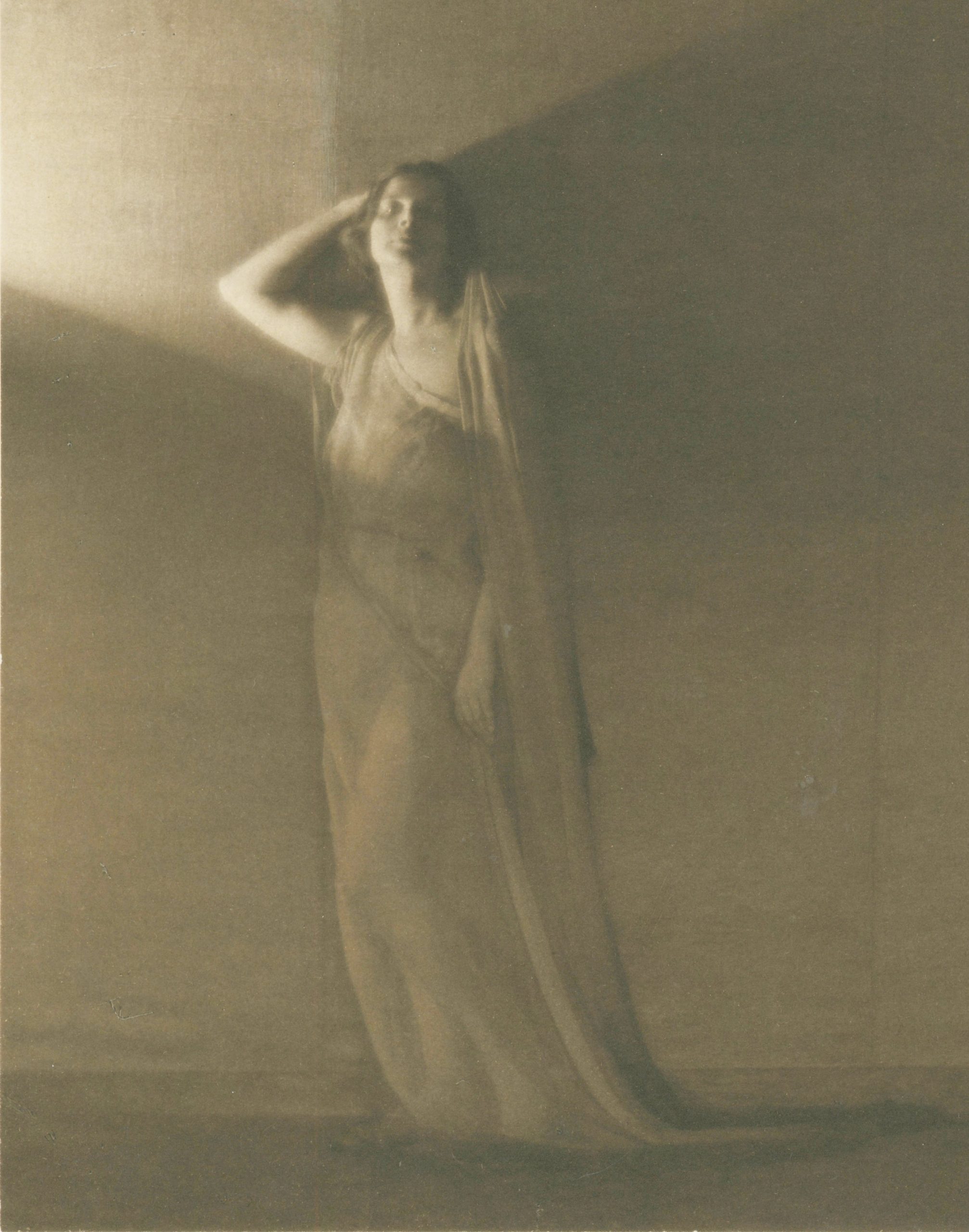

Durrant’s sister, Maud, studied music and dance in Europe. Years after her brother’s execution, she was the toast of London using her stage name, Maud Allan.

“Information was received here yesterday that Maud Allan, the mysterious (performer) at the Palace theater in London, is none other than Maud Durrant of San Francisco, sister of Theodore Durrant, who was hanged for the murder of Blanche Lamont 13 years ago. (Previously,) all that was known of the wonderful dancer was that she was an American, whose success was as sensational as her art,” reported the Associated Press, April 19, 1908.

She is best known for creating “Vision of Salome,” based on the Oscar Wilde play, “Salome” in 1906. Her dancing and storytelling inspired what is known today as modern dance.

She was also an author, publishing an autobiography titled “My Life and Dancing,” in 1908.

With silent movies making a splash, filmmakers turned to popular stage performers at the time. In 1915, she starred in the silent film “The Rug Maker’s Daughter.” She later retired, returned to California and taught dance. She died in 1956.

Others involved in the case

The Durrant case was in the public eye for so long, those associated with it were also of public interest.

“Caroline S. Leak, one of the most important and sensational witnesses in the trail of Theodore Durrant died suddenly yesterday at her residence,” reported the San Francisco Call, July 2, 1899. She was 70. “At the time of the tragedy in the belfry of the Emanuel Baptist Church, Leak resided across the way from the church. She was sitting at the front window of her house and saw Durrant and Blanche Lamont enter the side door of the church together on the afternoon on which the murder occurred. That was the last time Lamont was ever seen alive.”

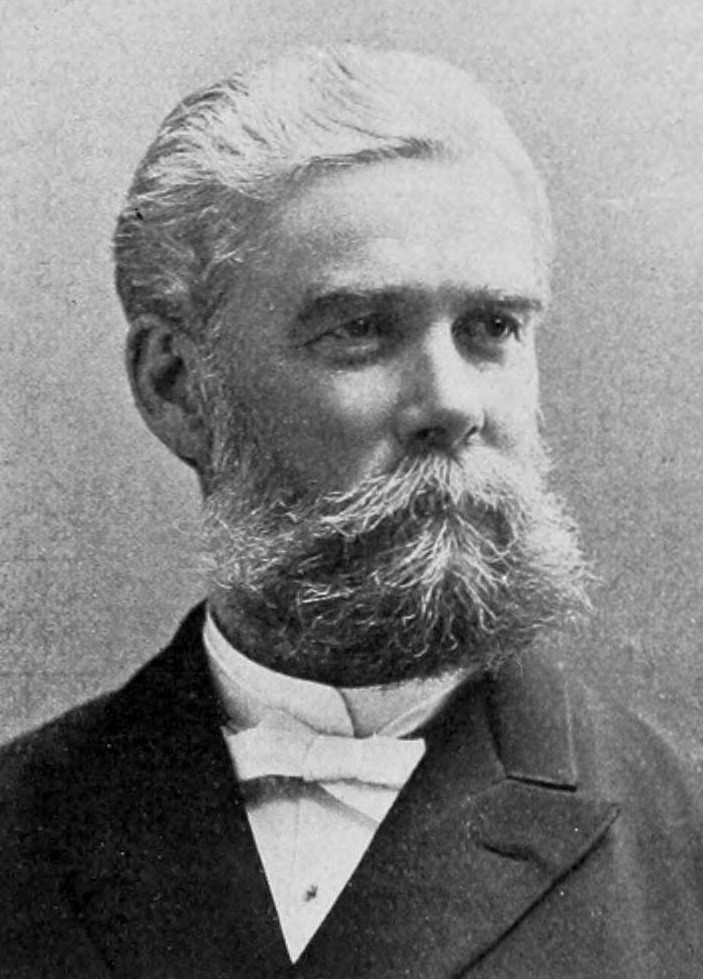

Eugene N. Deuprey served as one of Durrant’s defense attorneys. He was 55 when he died. “Deuprey was a family figure in legal and political circles,” reported the San Francisco Call, Oct. 5, 1903. “(He) gained further prominence as the attorney for Theodore Durrant.”

Dr. John S. Barrett, San Francisco’s autopsy surgeon who examined the bodies of Lamont and Williams, died at age 37 in Arizona, according to the San Francisco Call, Dec. 11, 1907. “Barrett, a young physician who figured prominently in the Durrant murder trial, died at Prescott, Ariz., on Monday. He was a native of Sacramento. His testimony formed an important link in the chain of evidence that sent the murderer to the gallows.”

“Judge J.T. Coffman and General John Dickinson have formed a law partnership,” reported the Sotoyome Scimitar, March 30, 1909. “General Dickinson is well known throughout Sonoma County, as well as elsewhere, identified with many prominent cases. He defended Theodore Durrant through his long fight for life through all the courts of the state and the supreme court.” He died in 1909 at age 58.

The prosecution, judge and detective

In 1910, “Captain William Barnes, one of the prominent attorneys of the west, died early this morning at his home at Salada Beach. (Kidney) disease is given as the cause of death. While district attorney of San Francisco, he secured the conviction of Theodore Durrant, who was executed at San Quentin prison,” reported the Los Angeles Herald, March 14, 1910.

“Judge who sentenced Durrant dies at Bay,” reads the headline in the Sacramento Union, Dec. 13, 1915. “George H. Bahrs, San Francisco attorney and former superior court judge, died here (on Dec. 12). He served as superior judge from 1894 to 1900, and it was in his court that Theodore Durrant received his final death sentence. Judge Bahrs, who was 53 years old, served San Francisco as civil service commissioner under three administrations.”

In 1910, a former detective was promoted in the city’s police department, taking the top job. “The appointment of John Seymour to be chief of police gives excellent promise,” reported the San Francisco Call, Oct. 3, 1910. “As a detective, Seymour ranks among the best. It was his work largely that brought Durrant to the gallows.”

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.