An 1877 report of the prison directors shows the determination of San Quentin staff as they dealt with a devastating fire that destroyed housing for 200 as well as kitchens, the mess-hall and workshops. The report also sheds light on the views of prison management regarding rehabilitation efforts.

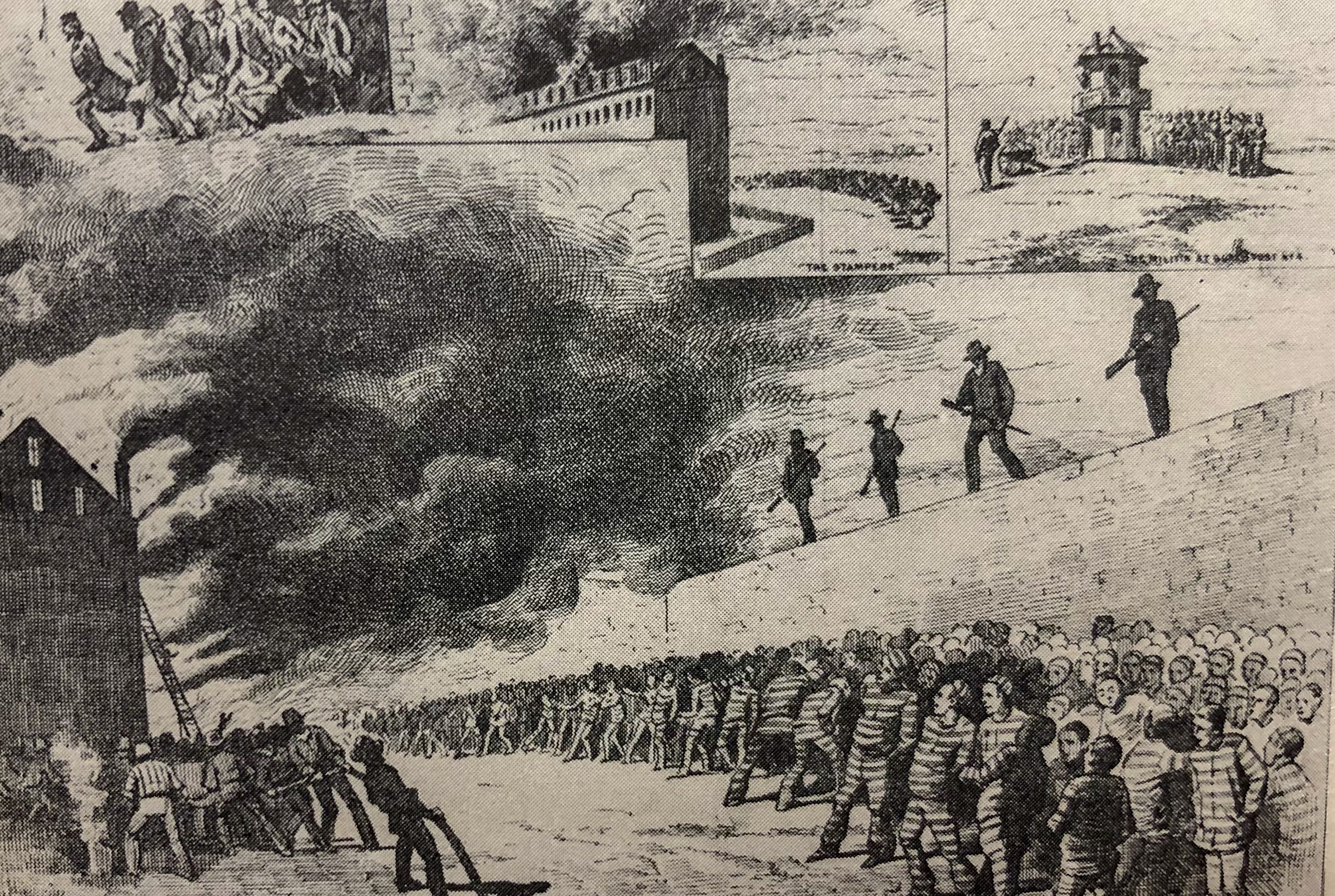

On Feb. 28, 1876, fire swept through part of San Quentin State Prison, destroying “the main workshops and machinery” as well as the kitchens, according to Lt. Gov. James A. Johnson, in his biennial report as the prison director. The military and police from San Francisco, numbering some 83 strong, secured the prison’s perimeter while inmates, staff and firemen from San Francisco fought the blaze.

Examine the devastating San Quentin fire

While the state report doesn’t give many specific details, newspapers at the time covered the San Quentin fire story.

“The main shop … a brick building three stories high on the east side and four on the west (due to a slope), … contains a furniture factory, … shoe shop, … prisoners’ dining room, kitchen and quarters for Chinese convicts, … it also contained the prison library of (up to) 4,000 volumes,” reported the Sacramento Daily Union, Feb. 29, 1876. The fire destroyed the building.

The San Quentin water pressure proved insufficient to fight the fire so incarcerated men began a bucket brigade.

“Several lines of hundreds of men were set at work carrying water in old fashioned style. Blankets were brought out and spread on the ends of the prisons and kept wet down. The hose was burned, and burst, and proved of no account, even if the water pressure had been good. The balconies at the ends were burned, but, by the prodigious labor of the (bucket brigades), the prisons were saved,” reported the Daily Alta California, Feb. 29, 1876.

“The flames spread rapidly and soon enveloped every portion of the building. The contents of several stores were (highly combustible). The San Francisco firemen arrived before (6 p.m.) and set themselves at work, the engine playing from the reservoir. As soon as the building (was) afire, the water pipes inside the building were burned, and the water wasted itself in the fire. (This) circumstance reduced the pressure from the (fire hydrants) in the yard. The absurdity of relying on a water supply for fire purposes through a three-inch pipe was demonstrated in the most unmistakable manner. The insecurity of rotten or second-class hose, as compared with genuine carbonized hose, used in the fire department, was further shown.”

After their hard work, the incarcerated population was locked up at sundown while the “firemen (worked) the (smoldering) ruins. … The whole number of (incarcerated) was 1,050, among whom there seems to have been no spirit of insubordination, but a unanimous disposition to do all in their power to assist in saving the property threatened,” reported the Daily Alta California. “It was certainly by their efforts that the (cell buildings) were saved intact. At nightfall, the yards were quiet and all danger believed to be over.”

Inmates credit San Quentin yard captain for inspiring them during fire

The incarcerated population said staff kept them motivated to save San Quentin from the fire.

Captain A.C. McAllister, who had worked at the prison for only six months at the time of the fire, had already earned himself a reputation as a “gentleman as well as a disciplinarian” among the incarcerated population, according to the Daily Alta California, March 1, 1876.

“He had no sooner pledged his word that good behavior should be noted and reported, and the persons recommended for favor – that now was their chance, and for them to show the stuff they were made of – than the effect spread through the ground, and animated the better principles in those addressed.

“Following it up, the Captain (pulled) out his notebook and commenced his proposed ‘roll of honor,’ sighting out and securing such individuals as would most likely be leaders. It was done very rapidly … and that vast crowd were quickly turned to, under order of the officers, working with a will and recklessness of personal danger which it is believed few freemen would have evinced.”

According to the newspaper, inmates doused blankets with water, wrapped themselves in them as protection from the flames and smoke, then battled the blaze.

“(With this method they) withstood the fire and heat with unflagging determination, until they got the best of all danger. Then, to crown the climax of this wonder – the (order) which sent all hands again to the cells which they might easily have destroyed,” the paper reported.

Looking back on that day, the captain said, “There are 150 men in those cells who deserve pardon today.”

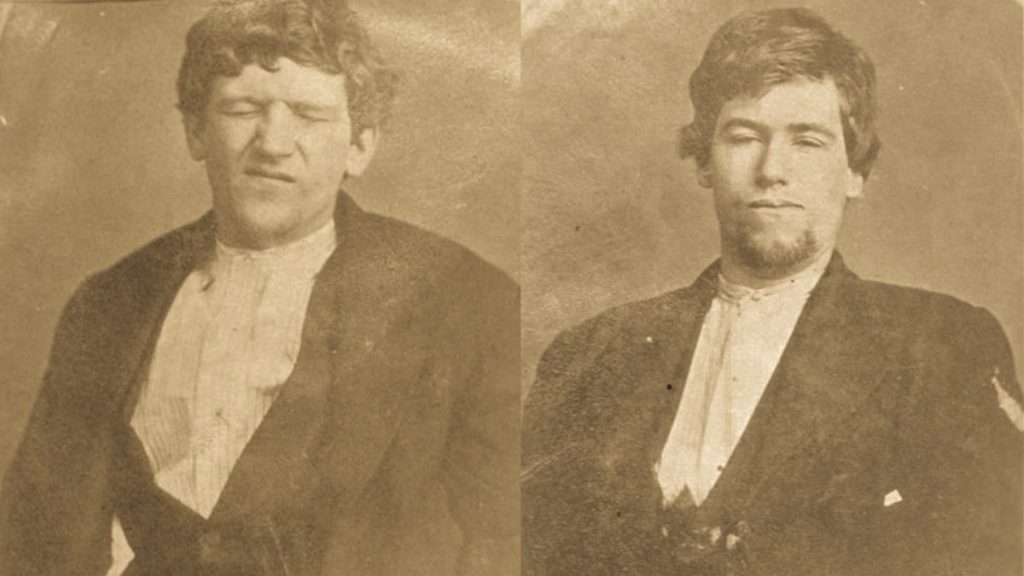

McAllister pointed to convicted forger Newt. Morgan, chief clerk in the Captain’s office, “who rendered the most important service during the excitement of the fire and was in the thickest of the battle at the balconies of the prison, and elsewhere, assisting the officers and directing the men. The Brotherton brothers were also engaged in meritorious services and received high praise. Among others in the same category were ‘Butt’ Riley, King of the Hoodlums as he was termed, (as well as) Charley Kuchel, Ned Eagle, Bob O’Malley, Dan Green, Wm. McGrath, Geo. Hoge, Bill Winkley, Tom Campbell, Jack Jones, John Kelley, Dan Haley, Tom Jackson, … John O’Brien, F.P. Birney, James A. Cotton and Thomas Woody.”

There were only four minor injuries attributed to the fire, according to state prison surgeon Dr. Pellem. The hospital, located next to the shop that burned to the ground, was evacuated of its 35 patients during the blaze.

Adapting to the aftermath of the San Quentin fire

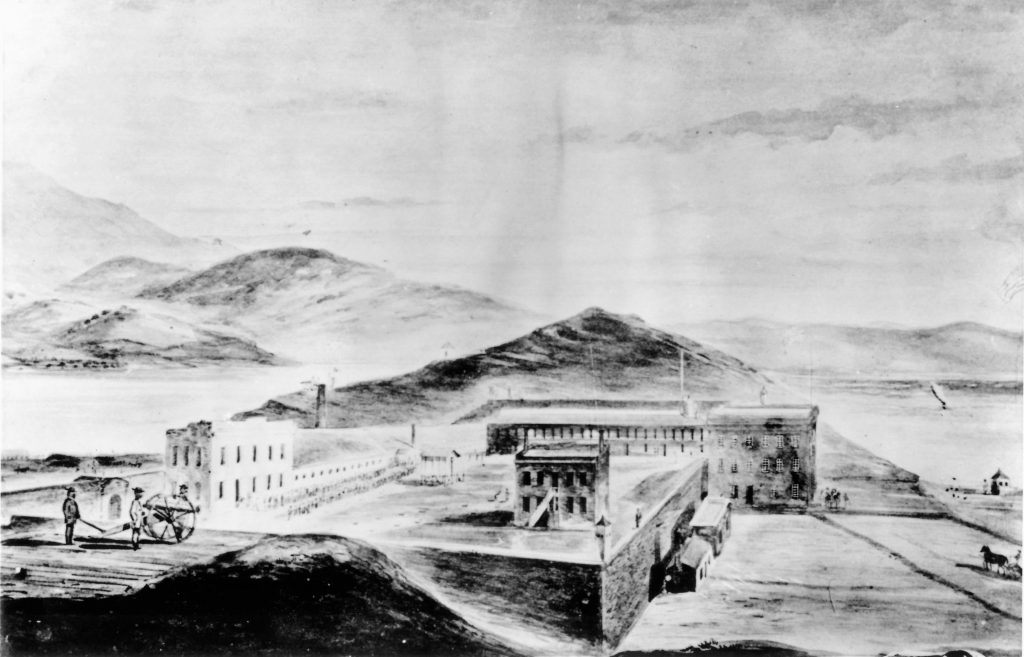

This sketch shows San Quentin as it was in the 1870s. (CDCR file photo.)

From 1875 to 1880, James A. Johnson was lieutenant governor for California.

“Besides the great loss to the state by the destruction of the buildings and other property, other losses accrued. The breaking up of the contractors’ shops, and consequent loss of the wages of the men; the extraordinary expenses for all necessary things to feed and cook for the men; and the utter demoralization that naturally resulting from the throwing of the whole number of convicts together in an open pen, cooking, eating, jesting and frolicking amid the ruins of the old buildings,” Johnson wrote. “We were compelled to make the best arrangements possible for cooking and mess-room. At first we obtained a number of large iron kettles, and with these, set on rocks and bricks, the cooking was done. For mess-room the open air was used, the men receiving their food as best they could.”

Prison staff immediately went about trying to improve the situation for all concerned.

“We soon, however, dispensed with these temporary make-shifts,” he wrote. “(Instead we began) building wooden vats heated by steam, instead of using the iron kettles. These were put up in the wash-house where others were already in use for washing, which were also used for cooking. For mess-rooms, two wooden buildings, each one hundred by thirty feet, were hurriedly (erected). In the same hurried manner, to prevent further demoralization, and to secure the letting of a part of our idle force, we put up a two-story frame building for the California Furniture Manufacturing Company’s use. These temporary improvement cost heavily, although the waste lumber obtained when they were demolished has all be used for fencing or outbuildings of some kind.”

Johnson praised staff and inmates who responded responsibly during the fires and the rebuilding process.

“About the middle of May (1876), affairs became settled, since which time no similar institution was ever managed with more apparent satisfaction to all concerned – officers, guards and convicts. Where all have behaved so well, I cannot distinguish among officers to bestow praise. They have, one and all, done their whole duty; and even to the stewards, hostler and guards I extend praise for most efficient service. On account of the confusion caused by the burning of the shop buildings and the great number employed in rebuilding, handling and hauling material (to and fro), and in making brick – the being constantly outside the walls, in daytime, nearly or quite 225 men – we have been compelled to increase the guard force.”

Warden recognized offenders as individuals

Treating incarcerated people as human beings, while doing away with heavy handed policies, was the practice of Johnson, according to his report.

“The cruel and inhuman iron-will rule usual at prisons is not in vogue here. Instead, we treat all who will bear it — and most prisoners do — with kindness and even courtesy.

“The plan of individualizing each one, and recognizing each from all others, and requiring something of each as an individual, is the surest method of obtaining good government at an institution like this. I might with propriety say something, here, on the questions of prison discipline and management.

“The solitary system … never reclaimed any man, and never will; it is cruel, and more barbarous than capital punishment. The silent system is worse and more cruel. The system with corresponds to the enlightenment of the age is that know as the congregate system, where men work together and when not at work talk freely together. The reasons usually assigned by the advocates of the solitary and silent systems are strong reasons, though not the strongest, for the universal adoption of the congregate system,” he wrote.

Gathering public support

He also advocated for more input and buy-in from the general public.

“Proper legislation could be had, putting the institution under long or permanent control, subject to a board of citizens. (This board would be) of long or permanent duration, possessing power to make contracts for a term of years, then our entire force might be hired to advantage,” he wrote, referring to the state’s practice of allowing companies to hire inmate laborers, with funds going to the prison. He was adamant that the skills learned should be of use once an inmate was released. “The cost of maintaining convicts is not so much a matter of serious consideration as how to lessen their number, and how to reform them and restore them to usefulness. It is in the decreased number of the convict class, and in their reformation, that the money must be saved to the taxpayer, and society benefited in a thousand ways.”

Some inmate jobs and assignments at the time included 20 bricklayers, two “bath tenders,” three to the boiler house, 10 closet cleaners, nine door tenders, three working the donkey engine, five hospital cooks, seven to “Hood’s gang,” eight hod carriers, three in the lamp room, eight mortar mixers and carriers, three mattress makers, 18 in the shoe shop, eight in the tailor shop, four in the tin shop, four in the wood yard, 41 in the wash-house (laundry) and 12 yard sweepers.

The lieutenant governor turned his attention to making permanent improvements at the prison.

“(Improvements) as follows have been made, all of which are permanent except those before mentioned:

- Brick drying-house, 33×15 feet

- Addition to wash-house, brick, 35×20 feet

- brick boiler-house, for cooking, 26×12 feet

- two stairways, each 36×16 feet

- new brick addition to female prison, 44 feet long by 16 feet wide, two stories high, and divided into convenient rooms.

- The two old south cell buildings had each 100 feet of new roofing, and the balconies were re-planked.

- A new belfry has been placed over the front gate.

Making improvements

“After the fire, a large temporary bake-oven was erected, which had to be taken down after the erection of the new building. Seven large wooden vats, for cooking by steam; seats, desks, etc., in library and chapel; two dining-rooms, 100×30 feet each; frame house for furniture shop, 130×36 feet, two stories high,” he reported. “Outside the walls: About 1,100 feet of post and plank fencing, built of old lumber, obtained from the foregoing mentioned buildings when removed; hog house, 50×30 feet, with stalls; blacksmith shop, straw house and wagon house. … We also added to the stone cell building 48 iron cells.”

He was also concerned about the number of youth people incarcerated at the state prison.

“An earnest contemplation of (the number of incarcerated youth) ought to excite some action for the protection of boys against temptations to commit crime, which are so common in our cities,” he wrote. He blamed low-wage earning immigrants for a lack of work in the cities, leading to idleness and despair.

“Perhaps the most direct road to the rescue of this class is to afford them and their parents labor when they are in need and see that they perform it,” he wrote. “Had this state, for the last 15 years, been free from the curse of that idleness, resulting … from the habit of visiting the gin-mill den, it is not unreasonable to suppose the miserable parents of these miserable boys would today be industrious, thrifty, and honest people.”

Who was James A. Johnson?

James A. Johnson, born in 1829, moved to California in 1853, serving in the California State Assembly from 1859-1860 from Sierra County.

He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from 1867-1871.

He served as lieutenant governor from 1875 until 1880. After leaving this post, he moved to San Francisco where he was the Registrar of Voters from 1883-1884.

Aside from his medical degree, he was also an attorney.

He practiced law in San Francisco until his death at age 66 in 1896.

1877 prison by the numbers

- Pay in 1877 for the warden was $10 per day.

- Monthly salaries of $150 were paid to the captain of the guard, captain of the yard, commissary and resident physician; $125 to the clerk, turnkey and upper gate-keeper; $100 to the lower gate-keeper and engineer; $80 to the captains of the first and second night-watch; $65 to the first steward; $60 to second steward and hostler; $75 to the guard acting as flogger; $65 to the guard acting as receiver of freights; and $50 to each of the 55 guards.

- The cost to incarcerate an offender in 1877 was 42.7 cents per day.

- San Quentin’s incarcerated population included one 14-year-old, two who were 15, 11 who were 16, 24 who were 17, and 49 who were 18.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor, Office of Public and Employee Communications.