A new Women’s Ward matron in 1914 focused on mental health to help rehabilitate the women incarcerated at San Quentin.

In 1914, the effort to reform the two state prisons and further inmate rehabilitation was given special attention by the governor at the time. Moving the warden from Folsom to San Quentin unlocked a series of reforms implemented at the state’s oldest prison.

One of the new warden’s first priorities was to shake up the Women’s Ward at San Quentin. Jessie Whalen, an “expert psychologist” in rehabilitation, had a long career of public service.

She led efforts to focus on mental health at state hospitals and the prison system. When there was a call to war, Whalen enlisted and helped soldiers battling post-traumatic stress disorder.

Her story, like many early correctional staff, has been lost over time but helped shape today’s CDCR.

For Women’s History Month, Inside CDCR takes a closer look at Jessie Whalen, an early Women’s Ward matron and mental health advocate.

Rehabilitation-minded warden replaces matron

Whalen had a wealth of experience when she was hired by newly appointed San Quentin Warden James A. Johnston in 1914. She had earlier worked at state hospitals in Iowa and Wisconsin before moving to California to work at Patton State Hospital. She replaced longtime matron Genevieve Smith.

“Jessie Whalen, former matron of the Southern California State Hospital (at Patton), was appointed to the position. Warden Johnston said the change was for ‘the good of the service,'” reported the Morning Press, Feb. 20, 1914.

Whalen, a psychologist, fit into Johnson’s reform-minded model of running an institution. By today’s standards, the position of matron was something akin to a Facility Captain. The matron position paid $900 per month, close to what the sergeants earned at the time. The two captains – of the yard and guard – earned $1,600 to $2,100 per month.

When females were required to be in court, Whalen handled transport.

“Warden Johnston and Matron Jessie Whalen, with two prison guards, accompanied three women and two men prisoners to Sacramento Friday who were subpoenaed to testify at the impeachment proceedings before the Senate of Superior Judge Childs of Del Norte County,” reported the Marin Journal, April 22, 1915.

At the time, the judge was under fire for allegedly allowing witness tampering in the case of Ruby Bartol, accused of accosting her daughter with the help of other men. The case drew the attention of the governor and the state attorney general, ultimately resulting in paroles for all the accused. (Read the Ruby Bartol story.)

Matron attacked in uprising

Overseeing the Women’s Ward, sometimes also referred to as the Women’s Department, could be dangerous.

On Jan. 6, 1917, a riot erupted in the Women’s Ward at San Quentin, injuring the mental health proponent.

“Riot broke loose (at) the state penitentiary and tonight Miss Jessie Whalen, the matron, was nursing numerous bruises. (Meanwhile, five incarcerated women), alleged ringleaders in the outbreak, were (in separate cells) awaiting an investigation by the warden. The trouble started while the women were sweeping the corridors of the women’s quarters. With brooms for weapons, (they) sailed into each other with vigor, but when Miss Whalen, attracted by the noise of conflict, appeared on the scene, she became the object of the attack. The captain of the guard finally restored order, but not before the matron had sustained a black eye and other injuries,” reported the Associated Press, Jan. 7, 1917.

Ambushed by the inmates and surrounded, Whalen’s fate could have been much worse if not for some offenders who sought help. The warden’s investigation revealed “during the fight, other women prisoners set up a yell” to alert the guards, who rushed in to quell the incident, according to the Jan. 13 issue of the Sausalito News. “The fighting prisoners were locked up in separate cells. They will lose their good conduct credits and other privileges.”

Whalen joins military to help during World War I

At the start of the first World War, Whalen joined the U.S. Army.

“Miss Jessie Whalen, our former matron, is in the army as a nurse (serving) mental cases (and is) stationed at Camp Fremont,” Warden Johnston reported in the biennial report covering 1917-18. “Before this country entered the war and afterwards, the women inmates sewed and knitted garments to be sent overseas.”

The Army desperately needed medical staff. According to the U.S. Army’s website, “more than half of the women who served in the U.S. armed forces in World War I – roughly 21,000 – belonged to the Army Nurse Corps, and performed heroic service in camp and station hospitals at home and abroad. When the U.S. entered World War I, there were only 403 nurses on active duty, and the need for nurses continued to grow. These nurses found themselves working close to or at the front, living in bunkers and makeshift tents with few comforts. They experienced all the horror of sustained artillery barrages and the debilitating effects of mustard gas.

“Army nurses also played a critical role in the worldwide influenza epidemic of 1918, the single most deadly epidemic in modern times. An estimated 18 million people around the globe lost their lives; among those were more than 200 Army nurses.”

Women join workforce

With so many men fighting overseas, women filled vacant positions.

“Their efforts and contributions in the Great War left a lasting legacy that inspired change across the nation. The service of these women helped propel the passage of the 19th Amendment, June 4, 1919, guaranteeing women the right to vote,” according to the Army website.

After the war, she returned to Patton State Hospital. There, she helped soldiers overcome post-traumatic stress disorder, known as shell shock.

A 1920 Riverside County Fair featured Whalen and her work with physically and emotionally scarred soldiers.

“Expert psychologist from the state (hospital) at Patton will be sent an exhibit illustrating the work that is being done among the patients,” reported the Riverside Daily Press, Oct. 12, 1920. “Dr. Riley and Miss Jessie Whalen, psychologist, prepared the exhibit. Miss Whalen has been abroad and she is recognized as a brilliant exponent of methods of applied psychology.”

Her work helped thousands of veterans.

“To demonstrate the system of rehabilitating education, which the government is using among the disabled soldiers, six convalescents from Arrowhead Springs hospital and two aids or teachers will be at the fair. They will work in the space provided them in the educational tent, illustrating the hand craft and vocational training that is being used among the wounded and shell-shocked soldiers,” according to the newspaper.

Turns attention to women and children

Later, she served women and children as the director of a new concept — a farm. Opened Jan. 1, 1922, the State Board of Charities and Corrections lists Jessie Whalen as the occupational director of the Industrial Farm for Women at Sonoma. She eventually returned to Patton and later retired to San Diego.

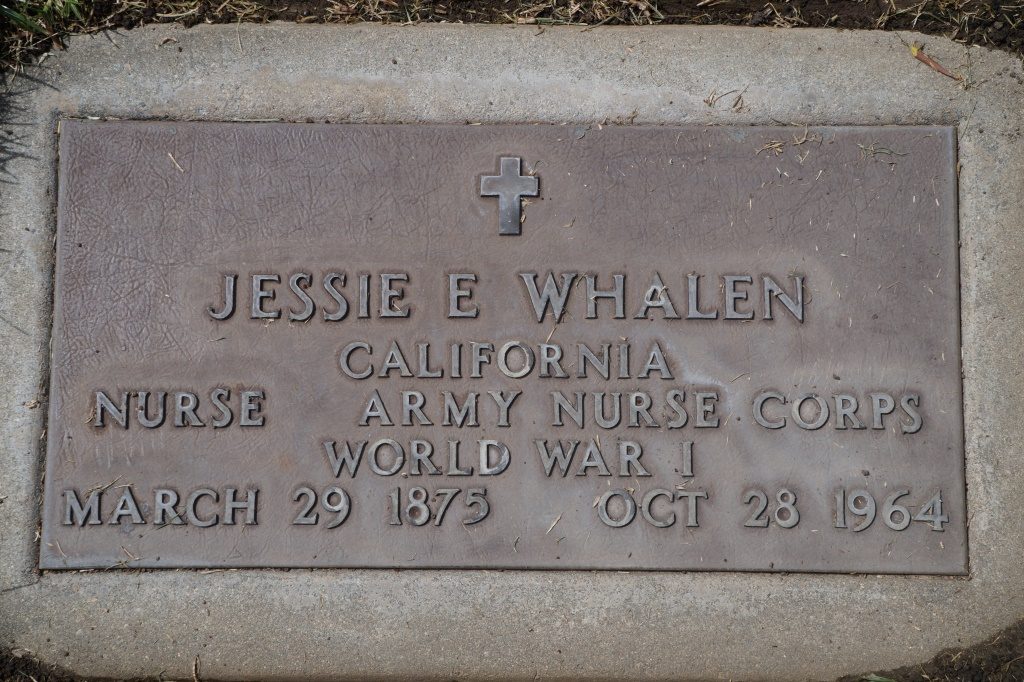

According to newspaper accounts, she kept in touch with Patton’s retired employees, organizing staff reunions. The former Women’s Ward matron, WWI veteran, and longtime mental health advocate died Oct. 28, 1964. She was 89 years old. Whalen was buried in Pioneer Memorial Cemetery.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.