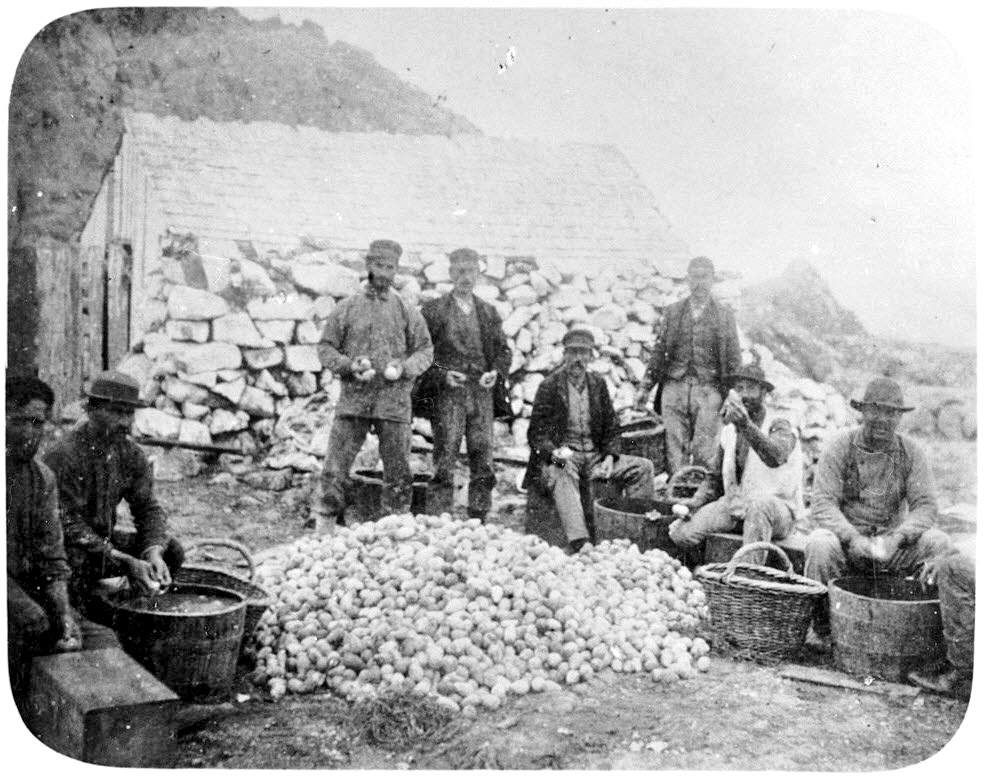

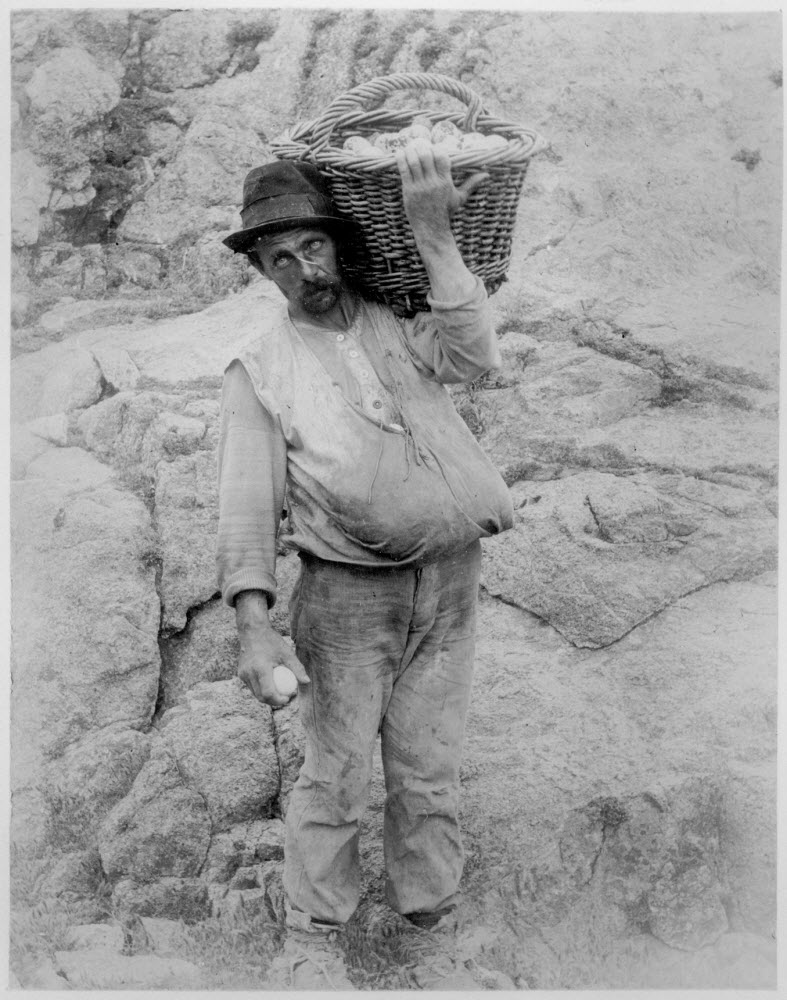

With people rushing west in the mid-1800s, food was scarce so some turned to raiding sea-bird nests, landing one man in San Quentin. At its most lucrative, eggs fetched $1 per dozen, the equivalent of $30 today. With so much money on the line, and a desperate public clamoring for more, the clash between rivals became known as the Great Egg Wars of the Farallon Islands.

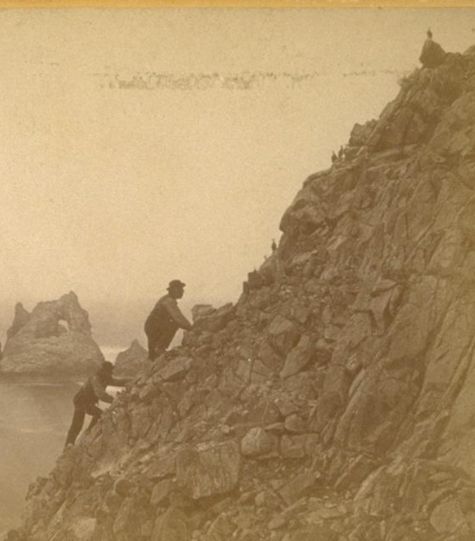

Island cliffs are nesting area for sea birds

The rocky, craggy cliffs of the Farallon Islands make up the largest murre rookery in the contiguous United States. The murre, a bird similar to a seagull or penguin, primarily lives on the sea, coming to land only during mating season, between May and August. To satisfy a hungry city, egg gathering groups battled for control of the islands.

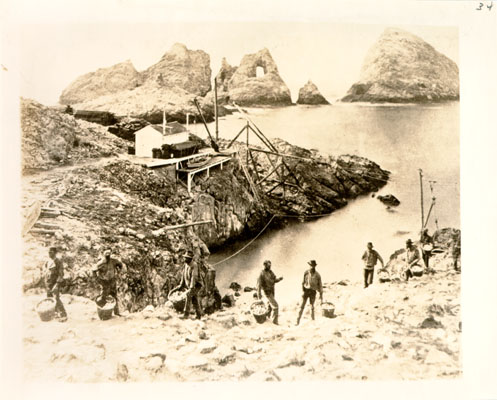

Formed in 1881, the Pacific Egg Company claimed exclusive harvesting rights to the islands. To keep away rival egg poachers, the new company even hired security guards.

At the same time, the federal government set about making the area safer by sending a crew to build a lighthouse on the islands. A few ships, transporting goods and people to San Francisco during the Gold Rush, crashed on the craggy islands. The activity upset the egg company, who sometimes fought with the construction crew and later the lighthouse keepers.

Competition turns to bloodshed

Ship Captain David Batchelder and his crew repeatedly tried to access the islands, but were consistently turned away by the egg company’s guards.

Treasure, contained in a delicate egg shell twice the size of anything chickens could lay, was waiting to be plucked from the dangerous cliffs. Deciding to take the south island by force, Batchelder and three ships loaded with 27 armed men arrived June 3, 1863.

Again, the private security force warned them against landing. Hurling insults at the men on shore, Batchelder and his crew anchored the ships in a cove, sheltered from the rough seas. Then, they turned their attention to whiskey. The next day, they returned in full force and opened fire.

The first to fall was egg company employee Edward Perkins. News reports claim he was able to get off a few rounds after being shot. Perkins was also a firefighter for San Francisco Fire Company No. 5.

Returning fire, the egg company guards shot five boatmen, driving them into retreat. The captain of one of the boats, shot below the throat, died two weeks later.

Batchelder and four of his crew were arrested. Charges were dismissed against all but two, with the captain standing trial for manslaughter. He didn’t get his eggs but instead received a San Quentin prison sentence.

Batchelder’s deadly scheme for eggs ends at San Quentin

During trial, the Pacific Egg Company guard foreman recounted the battle, placing full blame on Batchelder. In all, the battle was short, lasting 15 to 20 minutes.

“Perkins was shot during the first volley. He fired a musket first, subsequently (drawing) a revolver, fired two shots after he was struck, and then fell back and expired. The fatal shot came from a boat under Batchelder’s command,” said Isaac Harrington. “(I am) positive that the first shot came from the boats.”

Found guilty of manslaughter, and his appeal failing, Batchelder was sentenced to a year at San Quentin for manslaughter.

Assigned number 2692, he was received at San Quentin on February 26, 1864. The prison register notes he was 36 years old, born in Massachusetts, and sported a whale tattoo on his left forearm. His occupation is listed as seaman.

He was released after serving nine months of his one-year sentence.

Farallon egg gathering declines

By the mid-1860s, as domestic egg production increased, the price of murre eggs had fallen to 25 cents per dozen, the equivalent of $8.66 today. By the late 1860s and early 1870s, the price continued to fall.

“The Farallon (eggs) can now be had at reasonable rates at even the cheapest restaurants. The beautiful blue, green, brown, and red mottled eggs may be seen by the wagon load in our markets, and the material ‘to put in cake or fry with bacon’ can be purchased at prices within the reach of people of the humblest of means,” reported the Daily Alta California, June 4, 1868.

By the mid 1870s, with chicken ranches springing up in the hills outside San Francisco, egg production increased in the region.

Responding to the violence and devastation on the bird population, the federal government forbid commercial egg gathering on the islands. In 1881, U.S. Marshals and the military forcibly evicted the egg company.

Smaller egg gathering operations continued until the government again put a stop to the practice.

The California Academy of Science appealed to the federal government, resulting in an outright ban on all egg gathering. The 1909 executive order was signed by President Theodore Roosevelt.

Murre bird population still recovering today

As for the murre population, the birds are still recovering. Prior to the Gold Rush, it is estimated there were close to 1 million Farallon murres.

In 1854, a half-million eggs were poached from the cliffs of the Farallon Islands. To make matters worse, egg gatherers smashed eggs the first day of the season. This way, the next day, they knew the eggs would be fresh.

By the early 1970s, after some recovery, roughly 30,000 murres could be found on the Farallon Islands.

According to the Audubon Society, “The large number of birds and high diversity of species cause the Farallon Islands to often be referred to as the ‘Galapagos of California’ and the islands remain the most important seabird colony (on the west coast).”

Learn more about the Farallon Egg Wars in the Smithsonian Magazine.

See how Folsom Prison used agriculture to teach job skills.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.