CIM turns to teaching life and job skills

Created in 1941, California Institution for Men (CIM) was the fourth state prison but this one was designed to usher in a new era of rehabilitation. The idea was to replace hard stone walls with open space, dorm settings and opportunities for inmates to turn their lives around.

California Institution for Men’s early years

A need for another prison in the southern part of the state was addressed in a 1901 State Charities Conference in Oakland.

San Quentin Chaplain and Librarian August Drahms said the purpose of prison should be to reform the incarcerated person.

“It is the axiom in penology that the worst prisons turn out the worst prisoners and the best prisons turn out the best prisoners. The idea then of reformation strikes one at once,” he said.

Drahms went on to say another prison was needed.

“I advocate another prison (to be) built in the southern part of the state. The saving in railroad fare would pay for it. It should be composed of three sections: one for whom reform is impossible, one for first termers and one for young men. It would result in the moral and intellectual improvement of prisoners and pave the way for their reform,” he told the gathering.

Eight years later, the Board of Charities and Corrections again urged the state to create another institution for younger offenders.

“The (board claims placing) first termers in the state prison in cells with old timers, or those who are serving their seventh or eighth term, results in the younger (person) coming out much worse than when he went in,” according to newspaper reports.

Unfortunately, constructing a reform-minded men’s institution would take another four decades.

A 1940 issue of the San Francisco Chronicle reported “new plans for California’s prisons include a long-range program for separation of the 9,000 felons into different criminal types. San Quentin will house 3,000 convicts and will also serve as receiving ward. Incorrigibles and ‘tough guys’ will be sent to Folsom, which will be maintained as a maximum-security prison. Youthful first offenders will be routed to Chino, the new prison now under construction east of Los Angeles.”

Recruiting for rehabilitation

A 1941 advertisement seeking candidates for employment at “a Southern California prison … located at Chino” outlines some of the hopes and aspirations of what would later be dubbed the California Institution for Men.

The ad indicates the prison sits on “2,500 acres of fine farm land” and is to be a “minimum security institution for first offenders … (with the objective to) be the prompt rehabilitation of its inmates.”

It goes on to state, “Hope, encouragement, and the instilling of useful habits of work will be stressed to the end that men may be returned to society in the shortest possible time, prepared to take their part in the economic and social life of their communities, and to support themselves and their dependents.”

Called “supervising officers,” the ad indicates they will be “responsible for individual and group supervision of inmates assigned to them (to) include custody, direction of work details, and supervision of educational and recreational periods. Supervising officers will be required to govern and control inmates primarily by leadership, ingenuity, and force of personality, rather than by relying solely upon guns.”

They were to be paid a salary of $160 per month, capping at $200 per month after annual merit-based raises.

Dedicated on June 21, 1941, the California Institution for Men was the first major minimum security institution built and operated in the United States, according to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation website. It was the State of California’s fourth correctional institution and was constructed to relieve overcrowding at San Quentin State Prison (built in 1852) and Folsom State Prison (built in 1880).

CIM was unique in the field of penology because it was known as the “prison without walls.” The only security around the facility was a five-strand barbwire livestock fence, intended mainly to keep the dairy cows from wandering through the living areas.

A later CIM brochure, probably dating from the 1950s, indicated a starting salary at $619 per month, capping at $753 per month.

Rehabilitation focused

The new custody staff needed for the facility were hired with a reformer’s mindset, according to CDCR officials.

“With the opening of the California Institution for Men, Chino, under Mr. Kenyon J. Scudder in 1941, California’s correctional system was exposed to a group who were generally young and inexperienced in correctional matters, but well exposed to the ideas and thinking prevalent at the time in the fields of social science, psychology, anthropology, and related subjects in the universities,” wrote L.M. Stutsman, Deputy Director the state prison system, in a 1964 issue of Correctional Review.

The May 1994 issue of Correction News details some of Scudder’s methods.

“When Kenyon J. Scudder, a veteran penologist with progressive ideas, was appointed Warden of (CIM) in 1941, he insisted on having a free hand in the selection and training of the men who would staff the new institution,” the article states. “Of the 50 men Scudder selected to supervise inmates, 45 were college graduates, with four holding master’s degrees. In addition, nine … had general secondary teaching credentials.”

Training of the staff included “two hours each day of theory in handling men, some sociology, psychology, problems of discipline and the general philosophy of governing the institution; two hours each day … in martial arts; the balance .. was devoted to the work of the institution itself,” according to the article.

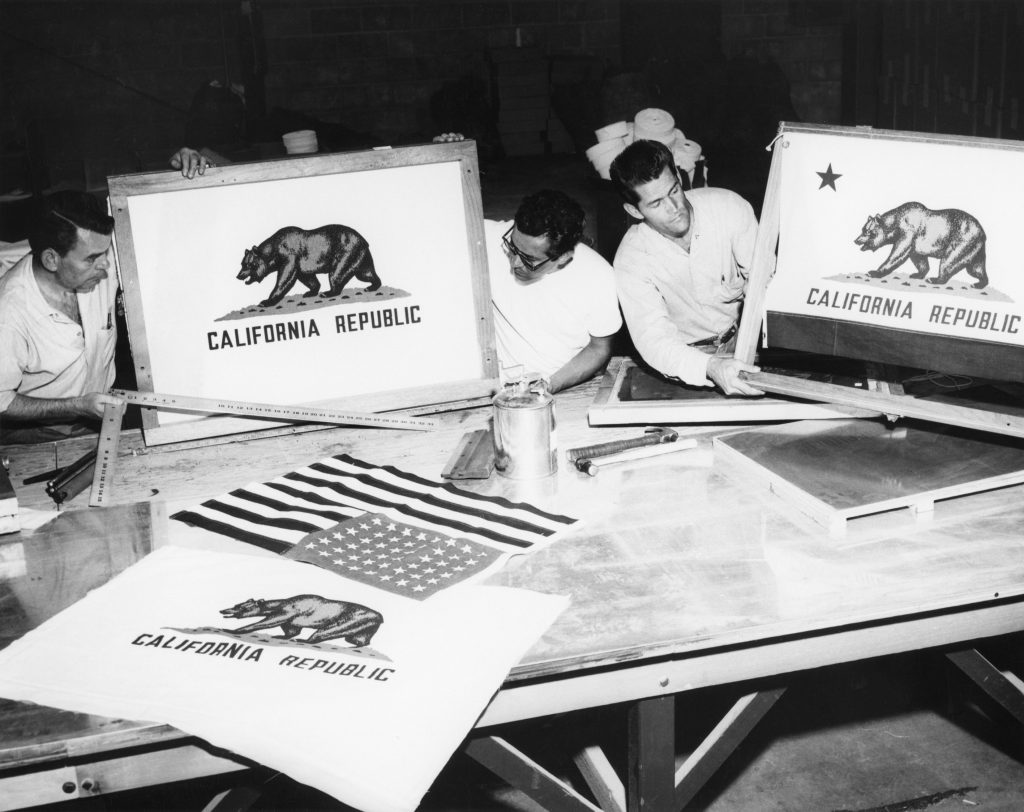

A pamphlet titled “The History of California Institution for Men” also states, “Strong emphasis was on vocational training and productive employment combining farming with industry.”

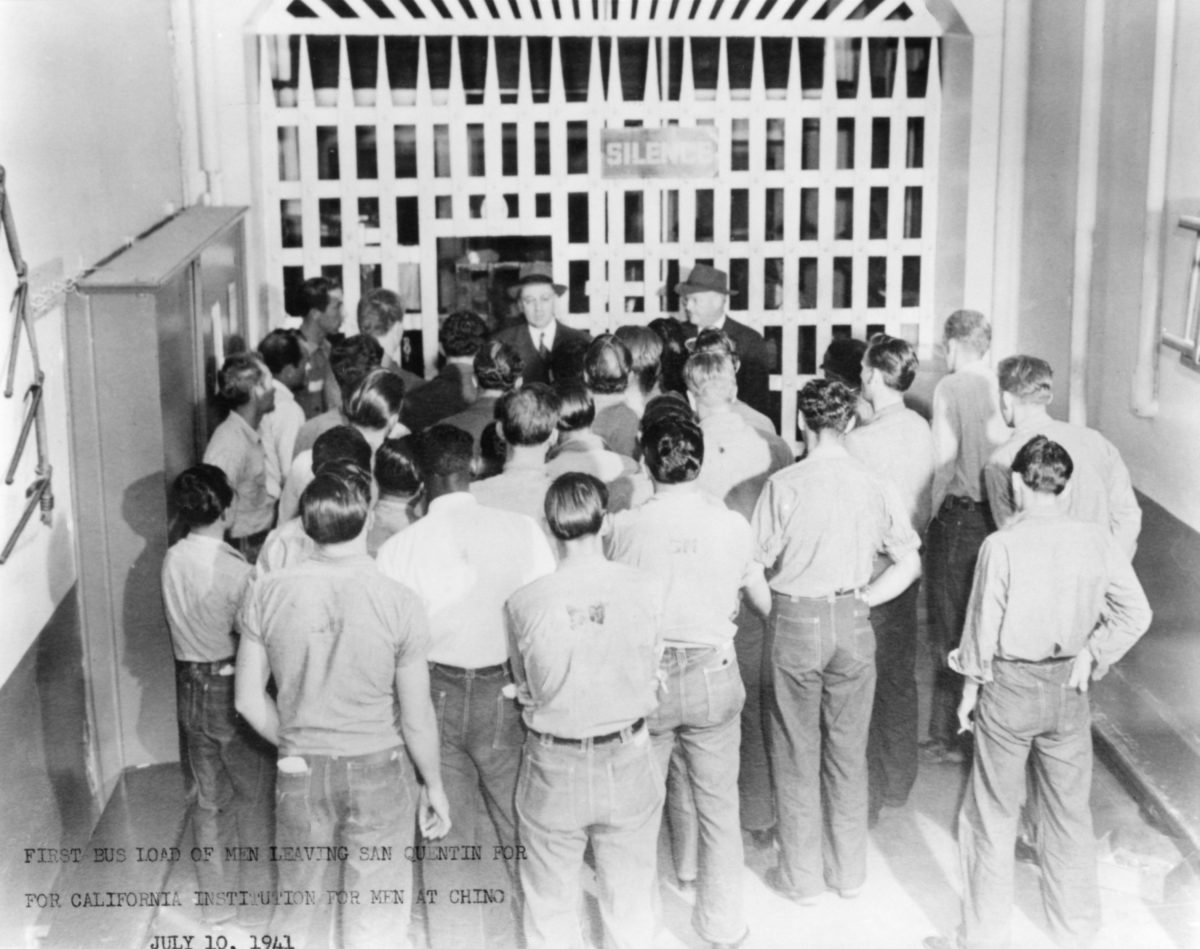

The first incarcerated residents were transferred from San Quentin on July 10, 1941. “These 34 carefully screened men would set the tone of the institution for many years to come,” the CIM pamphlet states. “One of the first changes (in the institution’s mission) came in 1941 when a Conservation Camp was opened in San Bernardino County. A 30-man crew was supplied from the institution. The primary purpose was to repair equipment and tools for the Forest Service, clear firebreak, and when necessary, fight brush or forest fires.”

“No individual institution embodied the spirit of reform better than the California Institution for Men at Chino,” according to “Prison Work: A Tale of Thirty Years in the California Department of Corrections” by William Richard Wilkinson. His book was published in 2005 by The Ohio State University Press. “Intended for younger, first-time offenders, or for those convicted of less serious criminal violations, Chino boasted a nationally recognized program.”

Chino’s first superintendent, Kenyon Scudder, later authored the 1952 book, “Prisoners are People.”

Spreading ideas

Those first CIM officers made their way through the state’s growing corrections department.

“As this group spread throughout the department and interacted with the experienced correctional personnel, a few sparks were struck but the results were generally constructive and productive of better programs,” Stutsman wrote in 1964.

When the California Department of Corrections was established in 1944, all the staff were rolled into state service.

“The blanketing of all positions under civil service within the department plus the arrival of Mr. Richard A. McGee as director in 1944, and his policy of inter-change of personnel between institutions, resulted in a synthesis of new and old ideas, techniques, and procedures throughout the department which, I am sure, was of mutual benefit to all institutions,” Stutsman wrote.

WWII veterans join ranks of Correctional Officers

One of CIM’s early Correctional Officers was William Richard Wilkinson. In his memoir, “Prison Work,” he details his career with the Department from 1951 to 1981.

“The inmates do their time, they get their training, they go out to get a job,” he wrote. “You could see that at Chino. And there was the education for the inmates. If you did not have a high-school education, then you spent half your day in class and the other half of the day picking tomatoes or shucking corn or whatever you had to do. You have to work to survive, and you have to have an education to make it. At Chino, they made room for both.”

He said the first night he worked, he learned a valuable lesson. As a WWII veteran, he said you learn how capable and smart you are. Working in a correctional facility, cockiness goes out the window.

“There were 70 men in the barracks. I sat in the middle in a little open office right next to the toilet area so that I could watch everything,” he recalled. “I could probably tell you every man who rolled over in bed, every man who passed gas, every man who snored. I had them all down pat.”

When he took a break, he was in for a surprise.

“About three o’clock in the morning, I went to eat my lunch. I opened up my lunch box, and it was empty. It had a note in it that said, ‘Thank you very much.’ Best break-in period I ever had. I knew I didn’t know a damned thing. That lunch box was washed out, and there was no way they could get to that (sink in the bathroom) without my seeing them and hearing the water running. And that lunch box was not out of my sight all night long. Anyway, that started me off right: they were clever and you had better keep your eyes open, and you don’t know a thing about them.”

Wilkinson also recalled the old wooden floors.

“Before they put the cement floors in the barracks, as you walked along, it would rock the bunks, and they were double bunks,” he wrote. “So you had to be kind of careful as you went down, or you would have inmates growling and complaining.”

He fondly recalled his time at CIM.

“The institution at Chino was different,” he wrote. “It was a new concept. All the traditional prison people put it down, in terms of prison.”

He said part of the difference was due to superintendent Scudder.

“Scudder had another principle,” he wrote. “He would not hire anybody who had worked in a prison before. He wanted people who didn’t have any prison background. He did not want to have a bunch of ideas to get rid of. He gave us his philosophy on Day One. We had not been there 15 minutes before we knew exactly what he wanted, how he wanted to do it and how we were going to help him do it.”

One of the big differences at the time? There were no locks on the doors back then, according to Wilkinson.

“So here was this man with ideas that were not traditional, and this would appeal to twenty-somethings who had just saved the world (in World War II),” he wrote. “It was a big operation, with the farm and cannery. We grew everything down there. Produce – corn and what have you – was distributed through the state by Prison Industries. And then we had the slaughterhouse and the dairy. … That was a great place. Probably for my own benefit, I should have stayed there. The program at Chino was ideal: education, vocational training.”

Wilkinson was promoted to Sergeant and later Lieutenant, moving on to California Medical Facility at Vacaville in 1955. In 1977, he transferred to the Correctional Training Facility at Soledad. He retired in 1981. His memoir was published in 2005 and he passed away in 2013.

Chino champion

One of the men who publicly rallied for a new first-offender prison at Chino was a newspaperman serving on the Board of Prisons.

Arthur R. O’Brien, known as A.R. to his friends, was born in Iowa in 1880. He graduated from Santa Clara University in 1898 and set out on a journalism career which took him to Cuba, Panama, Alaska and Oregon.

In 1910, he married Margaret McLellan, who had been working as a court clerk when they met.He settled in Ukiah and took over as publisher of the Republican-Press in 1920.

According to the Sausalito News (Jan. 9, 1947), “he was one of the first to advocate a span to cross the Golden Gate, fighting great political pressure to accomplish the engineering feat. He was appointed to the bridge district board in 1928 by the Mendocino County Board of Supervisors, serving continuously (for 20 years), the last two years as president of the board.”

In 1935, he was appointed a member of the State Board of Prison Directors by Gov. Frank Merriam. In 1938, he was elected president of the board, serving in the role for another two years.

During his time on the prison board, he was a strong advocate for “the creation of the new Southern California prison for first offenders at Chino,” according to the newspaper.

He also took up causes for the inmates. According to the paper, O’Brien was known for using his newspaper as a platform from which to effect change. “His vitriolic pen was particularly in evidence during his regime as prison director when he encountered prisoners he believed to be wrongly confined,” the newspaper wrote.

On a Tuesday morning in early January 1947, he succumbed to pneumonia in a San Francisco hospital. He was 66.

The newspaper referred to him as a “colorful figure” and an editorial opined, “His death is a loss not only to his home town of Ukiah, his home county of Mendocino, but equally so to the entire Redwood Empire and to the State of California.”

The paper also described his time on the Prison Board.

“Typical of his fighting, crusading character were his acts while a member of the State Board of Prison Directors from 1935 to 1940. It was O’Brien who fought and had abolished the practice of throwing prisoners in ‘the hole,’ or dungeon,” the paper wrote. “Much of his campaigning was carried out through the columns of his Ukiah weekly which he … published for a quarter century.”

More prisons to follow

The need for more prisons became apparent by 1947 when department Director Richard A. McGee issued a report to Gov. Earl Warren.

The May 8, 1947, issue of Sausalito News mentioned the report’s findings.

“McGee’s report stated California’s prison population now totals 8,323 and is continuing to climb,” the newspaper stated. “San Quentin’s prison population is 63 percent over its normal capacity. … Other prisons were equally overcrowded, according to the report. The women’s prison at Tehachapi is 73 percent over capacity, Folsom is 34 percent (over capacity) and Chino is 82 percent (over capacity).”

For 40 years, CIM remained without walls. The facility’s current walls were erected in 1983, along with guard towers.

War effort

In 1944, the Mira Loma Quartermaster Depot near Chino housed about 150 inmates from the California Institution for Men “who were establishing records loading and unloading freight for the Army” to help in the war effort, according to a 1964 Corrections News article.

‘Peter Pan’ stars goes to CIM

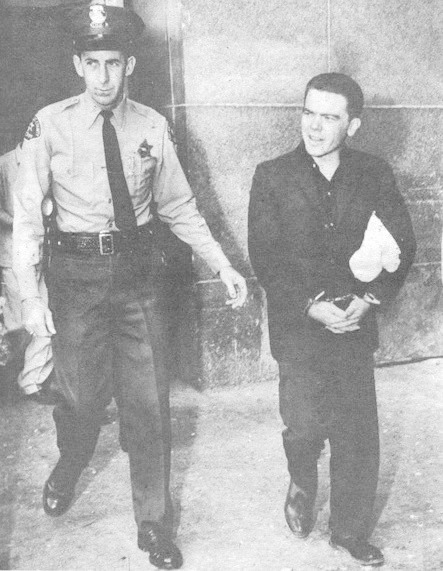

After starring in Disney films such as “Song of the South” and “Treasure Island,” actor Bobby Driscoll took on the lead role for which he was most well-known, “Peter Pan.”

Aside from his voice, his performance was filmed to give animators a reference.

The animators also based the character on his likeness.

Shortly after the film’s release, Driscoll was dropped by Disney and his acting career floundered.

As a young man, he turned to drugs and petty crime.

In the early 1960s, his behavior earned him a sentence in the drug treatment program at the California Institution for Men.

When he left the institution, he made his way east. At 31 years old in 1968, he died in New York City.

According to the coroner, there were no drugs in his system but his arteries had hardened from his earlier years of drug abuse.

His death didn’t become public knowledge until the early 1970s with the re-release of “Song of the South.”

Popular references

CIM is mentioned in popular songs and even a few movies.

- The 1955 movie “Unchained” was filmed at CIM and included footage of inmates. The film looks at Kenyon Scudder and his successes in rehabilitating inmates. Even more popular was one of the soundtrack’s songs, “Unchained Melody.”

- The facility is also referenced in the popular 1998 movie, “The Big Lebowski,” when bowler Jesus Quintana is said to have served “six months in Chino.”

Timeline

- June 21, 1941: New prison, referred to as Southern California Prison, is dedicated. It is later renamed California Institution for Men.

- July 10, 1941: First 34 inmates arrive.

- Aug. 2, 1941: Another 34 inmates arrive.

- December 1941: Population reported at 170 inmates. Also, 82 head of dairy cattle were donated by the state Department of Finance for use in a dairy. CIM purchased 100 head of beef cattle, used by CIM and other institutions. Later, the beef was sold to the U.S. War Department and shipped to the troops overseas. CIM purchased 22 wild horses from the Hearst Ranch at San Simeon. They were saddle-broken by the inmates.

- Early 1942: Department of Finance donated complete canning factory to CIM. It was originally set up in the culinary area and was called “Prospector.”

- 1947: Southern California Reception Guidance Center construction authorized at CIM.

- 1951: CIM population climbed to 1,235.

- 1959: Narcotics Treatment Control Program instituted to deal with short-term addicts.

- 1961: Saw the first woman counselor assigned to CIM, Billy Kaczmarek. She retired in 1980.

- 1968: The Family Visiting Program was offered, allowing qualified inmates to visit with their families in one-bedroom apartments on the institution’s grounds for 45 hours, according to November 1994 article in Correction News.

- 1974: Mary Grace Dick appointed as first female associate superintendent in a men’s prison.

- 1983: For the first time, a fence was erected around CIM.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Historical photos compiled by Eric Owens, CDCR Staff Photographer

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.