Firefighter training is core mission of conservation centers

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

and Lt. Robert Kelsey, Sierra Conservation Center

Photos compiled by Eric Owens, CDCR staff photographer

Inmates currently training as firefighters at Sierra Conservation Center (SCC) can trace the program’s roots to 1915 and the state’s efforts to construct reliable roadways in mountainous areas.

Those early highway camps evolved into harvest camps and eventually into today’s firefighting camps. SCC was established in 1965 to select and train inmates for those camps.

Building roads while building rehabilitation

A study by Columbia University, published in 1914, indicated using inmates to construct roads was beneficial to the state as well as the inmate. The study was part of the national committee on prison labor and reflected a renewed interest in long-term rehabilitation.

“The prisoner himself benefits most of all by his work on the roads,” reported the Red Bluff News on July 10, 1914. “The healthful outdoor labor, the better food, the incentive of the honor system and, above all, the wage … all combine to make him better fitted to re-enter society. The investigation proves conclusively that the building of good roads can be made a definite factor in the up-building of men.”

Eel River, circa 1930s.

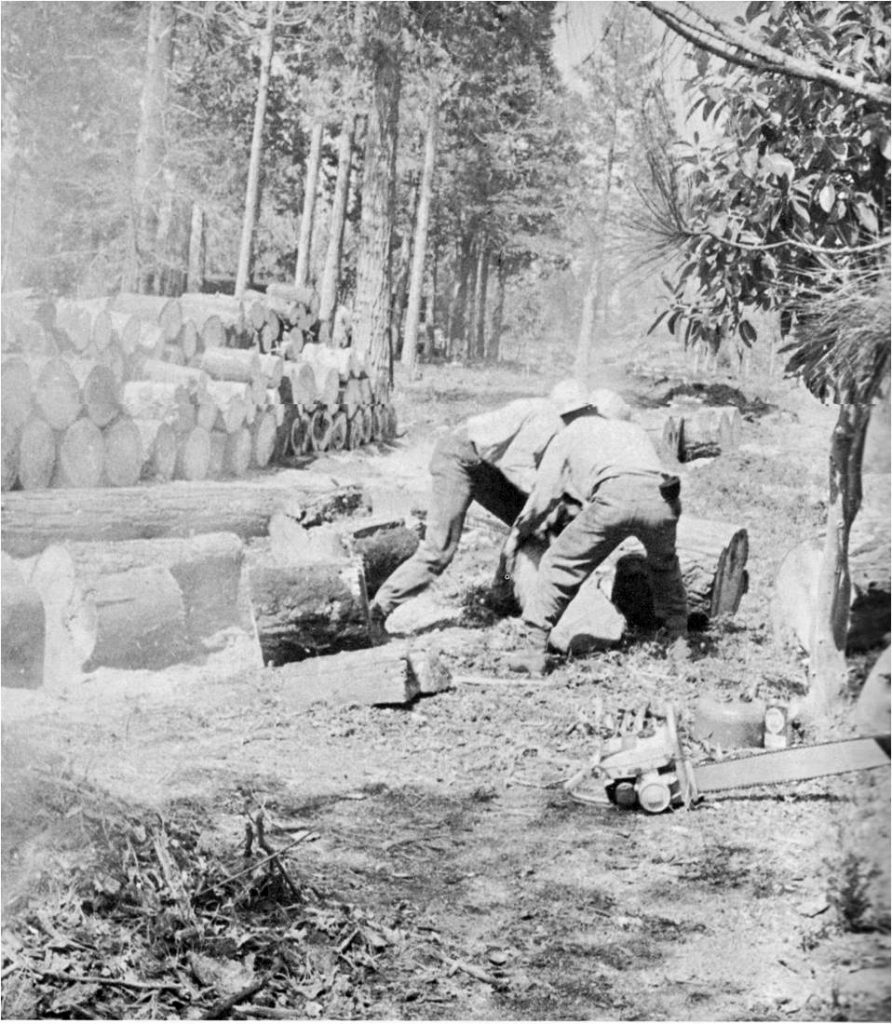

Eel River road work, undated.

The interior of an honor camp tent, undated.

Honor Camp #21, undated.

Honor Camp #21, undated.

Leggett Valley camp, circa 1917.

The interior of one of the tents in an honor camp, undated.

Counties drive need for road construction

Representatives of northern counties banded together to get roads constructed.

“The five northern counties ask that laterals be built connecting their county seats,” reported the Red Bluff News on Nov. 12, 1915. “State Highway Commissioner C.F. Stern (on Nov. 9) announced 31 convicts had left San Quentin Prison (for) Mendocino County, where a second convict labor camp will be established. … The second camp is to be established five miles north of Leggett Valley on the South Fork of Eel River, where the first camp is located.”

“The first camp is progressing in a very satisfactory manner,” said Stern in the 1915 newspaper article. “The men are doing good work on the highway and there have been no violation of the camp rules.”

With 1915 showing progress, more camps were established.

“Convict camp to be established in Shasta County,” read the headline for a story on July 7, 1916, in the Red Bluff newspaper. “The Supervisors were notified (July 6) that the sixth convict camp will be established inside of two weeks. The convicts are to work on the Redding-Alturas lateral, reducing the grade of the road up Manzanita Hill to Round Mountain.”

Another camp was formed near Susanville.

“(On July 24 in Westwood), T.A. Bedford, Division Engineer for the State Highway Commission, visited this section with Supervisor L.R. Cady to arrange for the convict labor camp which is to be in operation near here before the middle of August,” the Red Bluff newspaper reported on July 25, 1916. “The first camp will be at the Devil’s Corral, about four miles outside of Susanville. It is planned to work over 12 of the worst miles of road between here and that town.”

In August, inmates started arriving.

“Sixty honor men from Folsom State Prison have arrived (in Susanville on Aug. 28) to commence work on the Red Bluff-Susanville lateral of the State Highway under the direction of Engineer E.F. Lowden. Only four guards accompanied the men,” reported the Red Bluff paper on Aug. 29, 1916. “The construction camp is situated one mile west of Susanville and is thoroughly equipped in every detail, ensuring the comfort and health of the convicts, who regard the trip in the nature of a summer vacation. Work will be started near Susanville and prosecuted toward Westwood.”

More camps were established in the 1920s. The Marin Journal reported on San Quentin prisoners sent to Shasta County.

“Warden James A. Johnston Monday night dispatched 26 San Quentin prisoners, under guard, to Ingot, Shasta County, where a new camp will be established as the headquarters for convict labor on the Redding-Alturas State Highway,” the April 14, 1921 newspaper reported.

The Red Bluff Daily News, dated April 27, 1921, reported on plans for more inmates to aid in the effort.

“A convict honor camp at Mineral, 45 miles east of Red Bluff, is planned in connection with the work to be started soon for constructing portions of the Susanville-Red Bluff road this year under direction of the California highway commission,” the newspaper states.

According to a 1995 California Department of Corrections pamphlet, “50 Years: Public Safety, Public Service,” these camps are the forerunners of today’s state Conservation Camp Program.

During World War II, inmate honor camps were used to help tend farmland to grow crops for the war effort.

“Both San Quentin and Folsom began sending inmates to help harvest wartime crops (in 1942),” the 1995 pamphlet states.

A scandal in 1943 closed down the harvest camps, but a few years later, a new kind of camp system was created.

Conservation Camp Program established

Following World War II, the state created the California Conservation Camp Program.

Karl Holton, director of the California Youth Authority in 1945, worked with the State Division of Forestry, Department of National Resources, to begin constructing forestry camps.

“Extensive forestry projects are carried on. These include reforestation, road construction, telephone installation and repair, blister rust control and forest fire fighting. In each camp the primary purpose of the project is training and every boy is taught the skills necessary for any job before he is assigned to it,” he wrote in a 1950 article for the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology.

“There is no form of work which will develop better character habits than out-of-door employment in the forests of the state,” stated the Department of Corrections biennial report in 1946.

The fire camps proved popular.

“I don’t care who they are, they saved my house,” wrote an elderly woman to Governor Brown in September 1961, according to the December 2009 Journal of American History.

These new fire camps would need inmates, carefully screened, selected and trained.

Legislature creates training system

As conservation camps were created, it became apparent an overlying system needed to be in place to help train and supply inmates to those camps.

State Sen. Stephen P. Teale, an osteopathic doctor, served in the Senate from 1953 to 1956 and again from 1966 to 1972. He co-authored legislation creating conservation centers.

On July 22, 1963, the state broke ground on the $9.2 million Sierra Conservation Center near Jamestown.

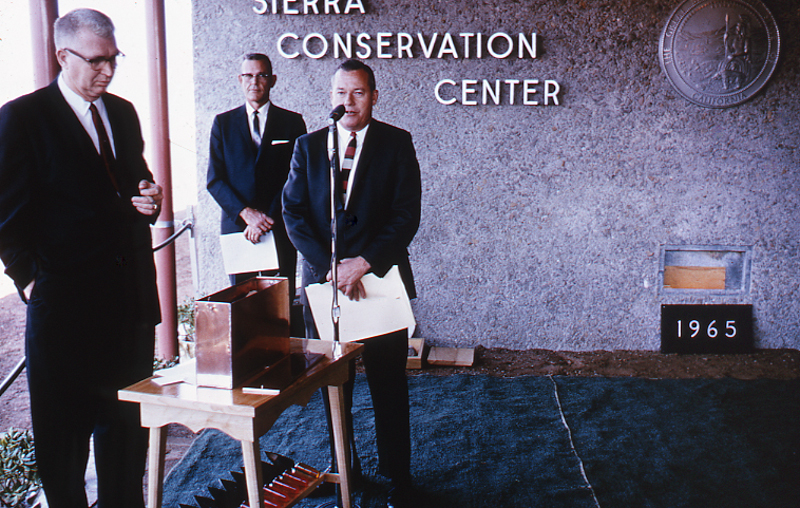

Breaking ground at Sierra Conservation Center.

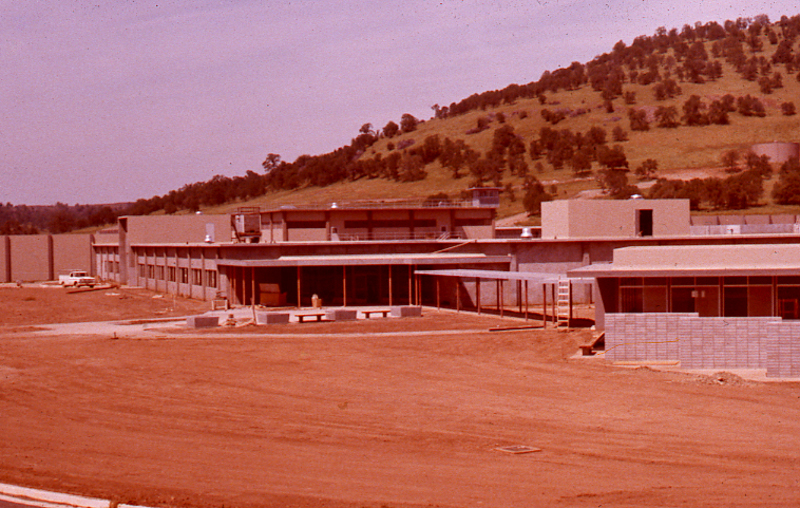

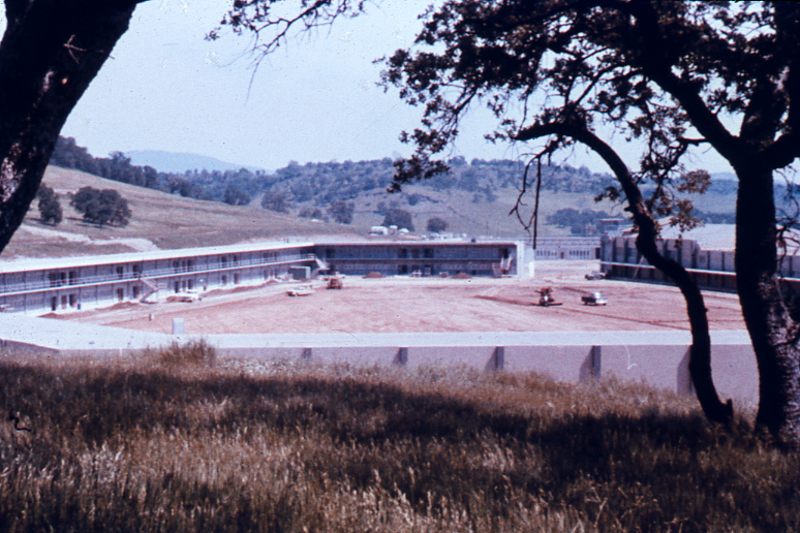

SCC construction, pre-1965.

SCC construction, pre-1965.

SCC construction, pre-1965.

SCC construction, pre-1965.

SCC construction, pre-1965.

SCC construction, pre-1965.

SCC construction, pre-1965.

SCC construction, pre-1965.

SCC construction, pre-1965.

SCC construction, pre-1965.

The site of Sierra Conservation Center, prior to construction.

“Each of these centers is designed to function as a supply, training and administrative hub for several outlying conservation camps. The camps, like the centers, are minimum-security facilities for prisoners carefully selected for such assignments,” reported the Lodi News-Sentinel on July 24, 1963. “In 1959, there were fewer than 1,000 inmates in 16 camps. Since then, 13 new camps have been developed and total inmate population is above 2,200.”

The newspaper went on to state, “Inmates train, study, exercise, take part in counseling, work together, under the supervision of state correctional and forestry personnel. They fight fires – 750,000 man hours of duty in 1961 – build and clear roads and trails, clear streams, fight erosion, help flood victims, improve wildlife habitats, improve and maintain state park facilities and campsites.”

The newspaper reported the benefits were twofold.

“Governor (Edmund G.) Brown, whose administration – and personal views on problems of corrections – must be given credit for the expansion of the program, said there are two (benefits): The protection and development of natural resources, and the rehabilitation of men. The first, he said, is essential; the second is nobler.”

W.D. Stovall, who helped design SCC, said the facility gave “the feeling of openness even though it is not.”

Sierra Conservation Center dedicated

Bryan Deavers seals a time capsule into the entryway at Sierra Conservation Center, 1965.

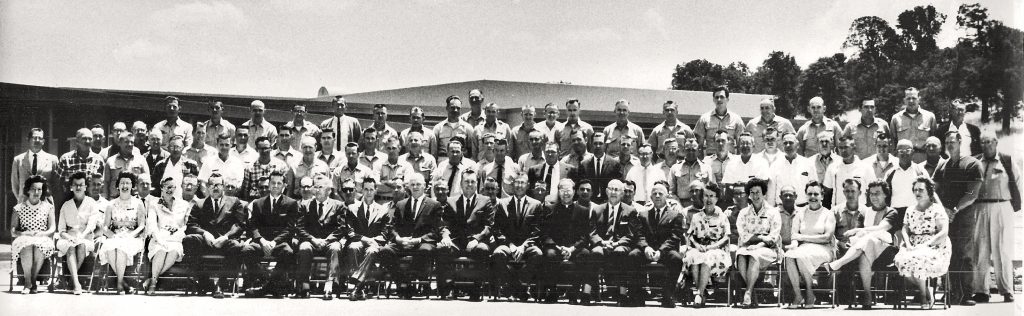

Crowd gathers to listen to Howard Comstock at the dedication of the new Sierra Conservation Center, 1965.

Laying of the cornerstone and time capsule at SCC, 1965.

The center was dedicated Oct. 9, 1965. Dignitaries from the region, including Sen. Stephen P. Teale, attended the all-day event.

Inmates demonstrated firefighting techniques as well as sandbagging. A marching band from Sonora High School performed.

There was also a cornerstone laying ceremony, complete with a time capsule. It was placed into the wall by Sen. Teale and sealed into place by Bryan P. Deavers, president of the State Building and Construction Trades Council.

What was in the time capsule?

- Roster of employees added by SCC Superintendent Howard Comstock

- The Nugget inmate newspaper added by Philip K. Glossa, Supervisor of Education, SCC

- Stockton Record newspaper added by Elizabeth McKnight, Central California News Editor, Stockton Record

- Modesto Bee newspaper added by Julian Fein, Modesto Bee reporter

- Union Democrat newspaper added by Jan Wyatt, Sonora Union Democrat reporter

- Microfilm of architectural drawings added by Paul Overmire, project architect with the Division of Architects, and W.D. Stovall, business manager of SCC

- County resolution added by Edward C. Pfeiffer, chairman, Tuolumne County Board of Supervisors

- Roster of Citizens Advisory Committee for SCC added by Fred J. Engle Jr., Deputy Director of the Correctional Conservation Camp Services Division of the Department of Corrections

- Forestry-Corrections camp agreement added by Lewis A. Moran, Chief Deputy State Forester, Division of Forestry

- Guest list and invitations for SCC dedication program added by Laurence M. Stutsman, Chief Deputy Director of the Department of Corrections

- Photo and biographical history of SCC first Superintendent Howard Comstock added by Walter Dunbar, Director for the Department of Corrections

- Department of Corrections Biennial Report added by Richard A. McGee, Administrator of the Youth and Adult Corrections Agency

- Newspaper story on a prison break added by Eugene Chappie, Assemblyman of the 6th Assembly District

- Copy of SCC dedication program added by Frank Mesple, Legislative Secretary for the Governor’s Office

- Copy of Dedicatory Address added by Sen. Stephen P. Teale, 26th Senatorial District

Women in corrections

Midge Carroll was one of the pioneering women in the department. She also served as an associate warden at Sierra Conservation Center.

When she started at SCC, she was one of four women at the institution. A few years later, there were 17 women working there, she told a newspaper on Nov. 13, 1979.

“This issue was the most explosive and divisive ever to hit the state department of corrections,” she said. “The realities of a woman going into a non-traditional job are really pretty scary.”

She told the newspaper, “State department of corrections research has shown women are doing quite well in their (prison) jobs since 1973. … Women want the same things from their job as men – recognition, success and a feeling of achievement.”

According to Carroll, SCC’s mission is important to society as a whole.

“The Sierra Conservation Center is the only prison in the state where inmates pay society for the crimes they have committed,” she told the newspaper.

In 1979, “the typical inmate is 28 years old and has committed a robbery or a burglary or a drug-related crime,” she said.

“Explaining that each prison in the state is designed to deal with a specific kind of inmate, she added that Sierra was designed to house the most manageable men in the prison system,” the newspaper reports. “The prison has both medium and minimum security units.”

According to the newspaper, “Besides fighting fires and working on flood control, Sierra inmates provide other services to the community such as making picnic tables for local schools, she said.”

Serving the community

In 1989, Museum Technician Diana Newington decided something needed to be done to showcase the history of chickens and the role they played at Columbia State Historic Park.

There were plenty of chickens at the park and many of them had taken refuge in the farm implement shed where they were soiling the antiques stored inside.

Undeterred, she began a four-year process involving multiple organizations, environmental impacts and archeology approval for the construction of a chicken coop.

“The Columbia maintenance staff worked with the Department of Corrections to have inmate crews from the Sierra Conservation Center construct the coop,” according to an online pamphlet provided by the Columbia California Chamber of Commerce. “The coop features individual nesting boxes with viewing areas for school children to observe the laying hens. The entire structure is designed to allow visitors an intimate look at the private lives of chickens.”

The coop was completed and in operation by 1994.

Projects large and small help communities around the state.

“When not fighting fires, camp crews are kept busy on public service projects, like clearing litter from highways or maintaining parks and other public lands. Camp crews also assist in cleanup operations after floods, earthquakes, toxic spills and other emergencies,” according to a March 1994 department brochure titled “Inside Corrections: Public Safety, Public Service.”

The brochure goes on to state, “Camp inmates provide a real economic benefit to local communities. In 1992, camp inmates worked nearly 9 million hours valued at $70.1 million.”

Rehabilitation behind the walls

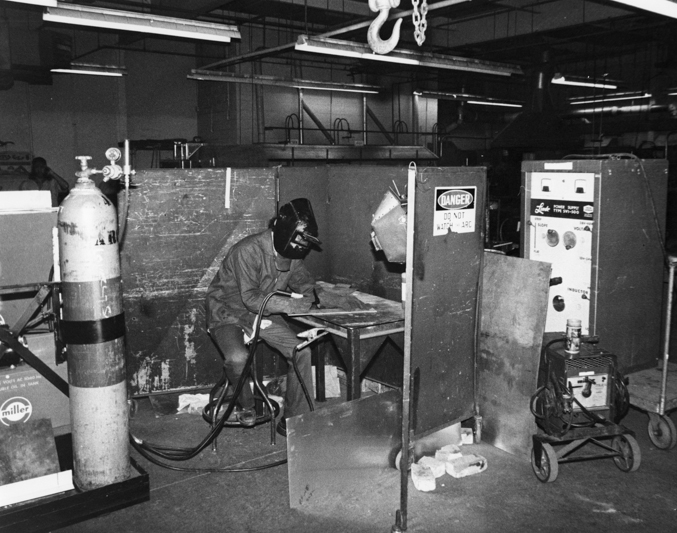

SCC inmates learn welding, undated.

Inmates learn the textile industry, undated.

A vocational shop at SCC.

On June 10, 2004, The New York Times published a front page article detailing a new program offered at SCC.

“The prisoners, whose crimes range from robbery to multiple homicide, were celebrating the completion of a 40-day Christian worship program outlined by (Rick) Warren in his book, ‘The Purpose Driven Life,’” the newspaper reported.

“The prisoners are the first Purpose Driven church in prison; this year, they added a Christian substance-abuse treatment program based on … Celebrate Recovery.”

The June 4, 2005 edition of the Modesto Bee also sported a story on the subject.

“‘It has made an impact on these guys,’ said Lt. Dave Espinosa. ‘It made a difference in our yard politics and the way these inmates carry themselves in the yard. It has helped with the interaction between the races.’”

Lt. Kenny Calhoun told the newspaper the programs are beneficial.

“The goal is to create some type of change for these guys, so when they get out, they think differently,” Lt. Calhoun said.

Others chose education to help with their rehabilitation.

The March 12, 2007, edition of The Union Democrat covered graduation ceremonies for dozens of inmates who earned GEDs, Associate of Arts degrees and certificates in carpentry.

Warden Ivan Clay said it was all about giving the men a chance at a new life.

“If they have educational and vocational tools, they have a much better chance of getting a job and staying out of prison,” Warden Clay told the newspaper. “That’s the whole goal. We have a very dedicated teaching staff, and I just let them do what they know how to do and this is the result.”

A former SCC inmate who was a paralegal studying to pass the state Bar Exam was a guest speaker at the ceremony.

“Your debt to society starts when you walk out those gates,” said Ray Robinson, the former inmate. “You have an obligation to change your ways.”

Former Correctional Officer slain

Correctional Officer Earl Scott came from a law enforcement family. His father and uncles were all California Highway Patrol Officers.

CO Scott worked at SCC from 1995 until 2001, when he left the department to follow in his father’s footsteps by becoming a CHP Officer.

For five years, he patrolled the streets until he was shot and killed during a routine traffic stop on Feb. 17, 2006.

“He was one of those elite types of individuals who was going to shoot up through the ladder, and there were people in our organization trying to get him to stay,” said SCC Correctional Officer Randall Harris in a Contra Costa Times report. “I have no doubt that if he stayed here he would have worked his way up to warden. And I would have enjoyed working for him.”

A section of Highway 99 in Stanislaus County was named in his memory.

Wardens at SCC

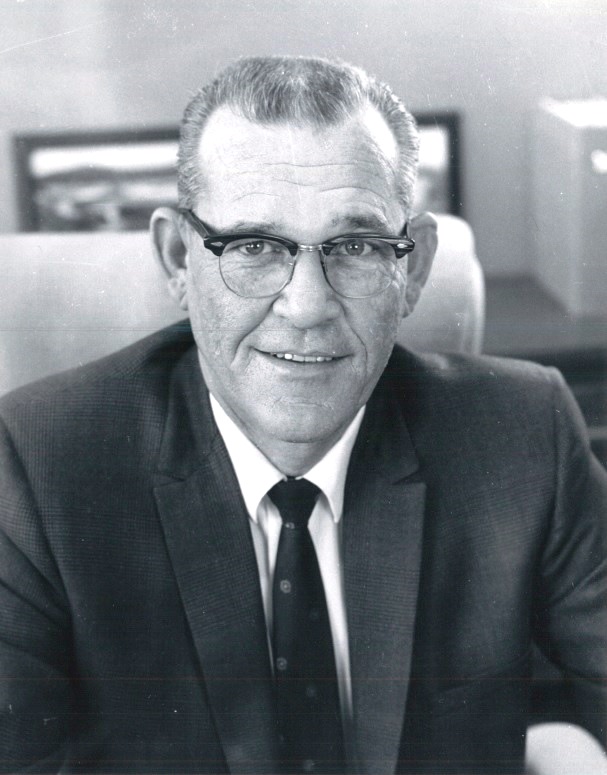

Howard Comstock

Robert Rees

Kenneth Britt

Robert Doran

Vernon Smith

Kingston Prunty

George Ingle

Franklin Powell.

Matthew Kramer

Ivan Clay.

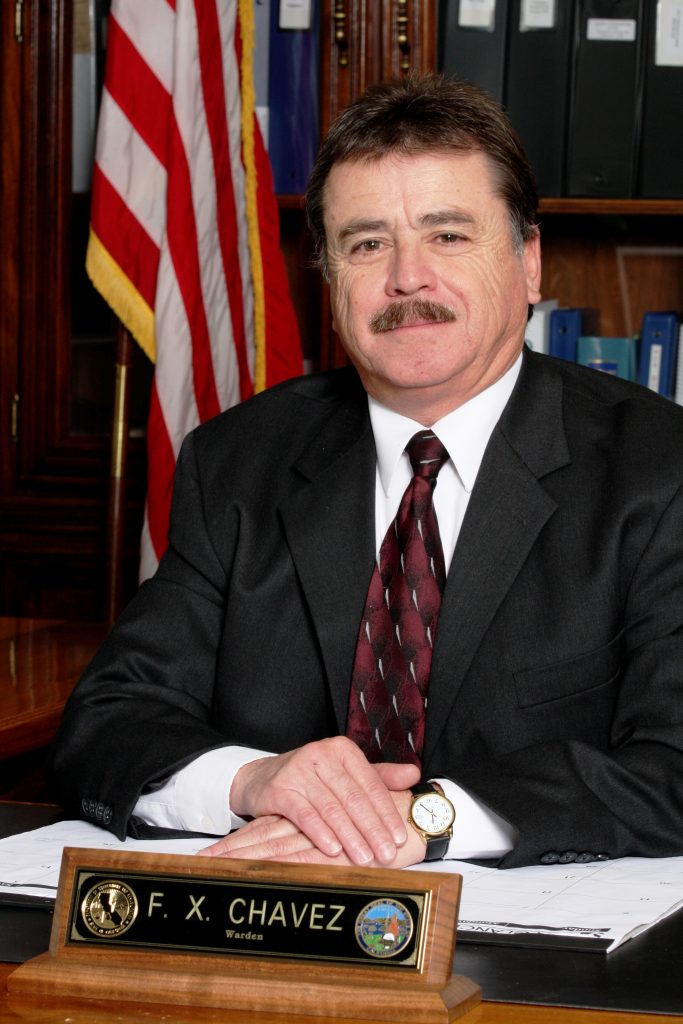

Frank Chavez

Heidi Lackner

- July 1, 1964-Sept. 20, 1973 Howard M. Comstock

- Oct. 7, 1973-Feb. 16, 1975 Robert M. Rees

- Feb. 17, 1975-June 30, 1983 Kenneth D. Britt

- Dec. 15-1983-Aug. 30, 1989 Robert Doran

- Nov. 7, 1989-Sept. 30, 1991 Vernon Smith

- April 6, 1992-Sept. 7, 1993 Kingston Prunty, Jr.

- Nov. 15, 1993-Nov. 13, 1994 George Ingle, Jr.

- March 22, 1995-March 21, 1996 Franklin Powell

- Oct. 2, 1996-May 13, 2006 Matthew C. Kramer

- July 19, 2007-Aug. 31, 2009 Ivan D. Clay

- Aug. 6, 2010-Aug. 30, 2012 Frank X. Chavez

- April 8, 2013-present Heidi M. Lackner

Timeline

- July 22, 1963 Sierra Conservation Center broke ground

- Oct. 9, 1965 Sierra Conservation Center is dedicated, cornerstone laid

- Nov. 20, 1985 Ground broken on new Level III facility, known as Tuolumne