Vacaville facility marks new era in treating offenders

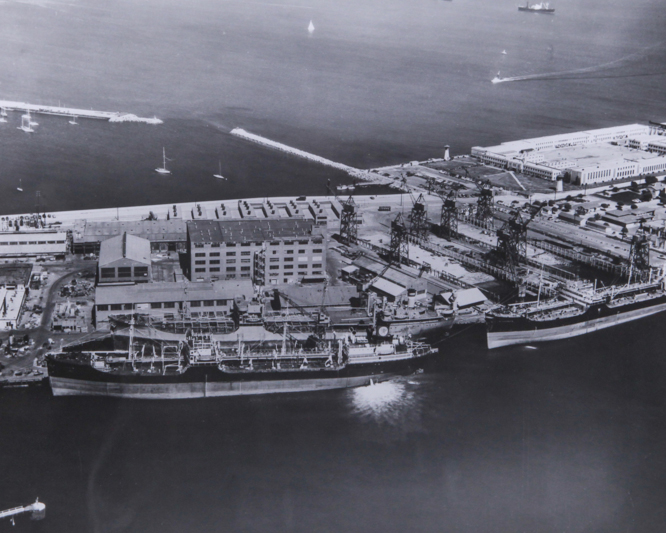

California Medical Facility (CMF) history begins in southern California and a former federal prison at Terminal Island, long before it opened in Vacaville.

When it activated in 1955, the facility became the first prison hospital in the nation.

California Medical Facility was actually the state’s second attempt at creating a psychiatric prison hospital, the first being recommended in 1890 and built on a bluff above Folsom State Prison. Construction was never completed.

Much like Deuel Vocational Institution’s early years, CMF began in a temporary spot until a permanent location was established.

Gov. Earl Warren’s 1944 plans to restructure the state’s prison system opened the way to establish a “psychopathic hospital” within the department.

In 1947 and 1948, the state purchased property in Vacaville to construct CMF. In 1949, the state legislature officially authorized the department to “build a permanent hospital/prison facility for psychiatric and diagnostic male felons” to be located “in or near Vacaville.”

The state budget in 1950 appropriated $6.4 million to construct CMF but first they opted for a temporary location at Terminal Island in San Pedro near Los Angeles. It would take another five years to construct and open a prison hospital in Vacaville.

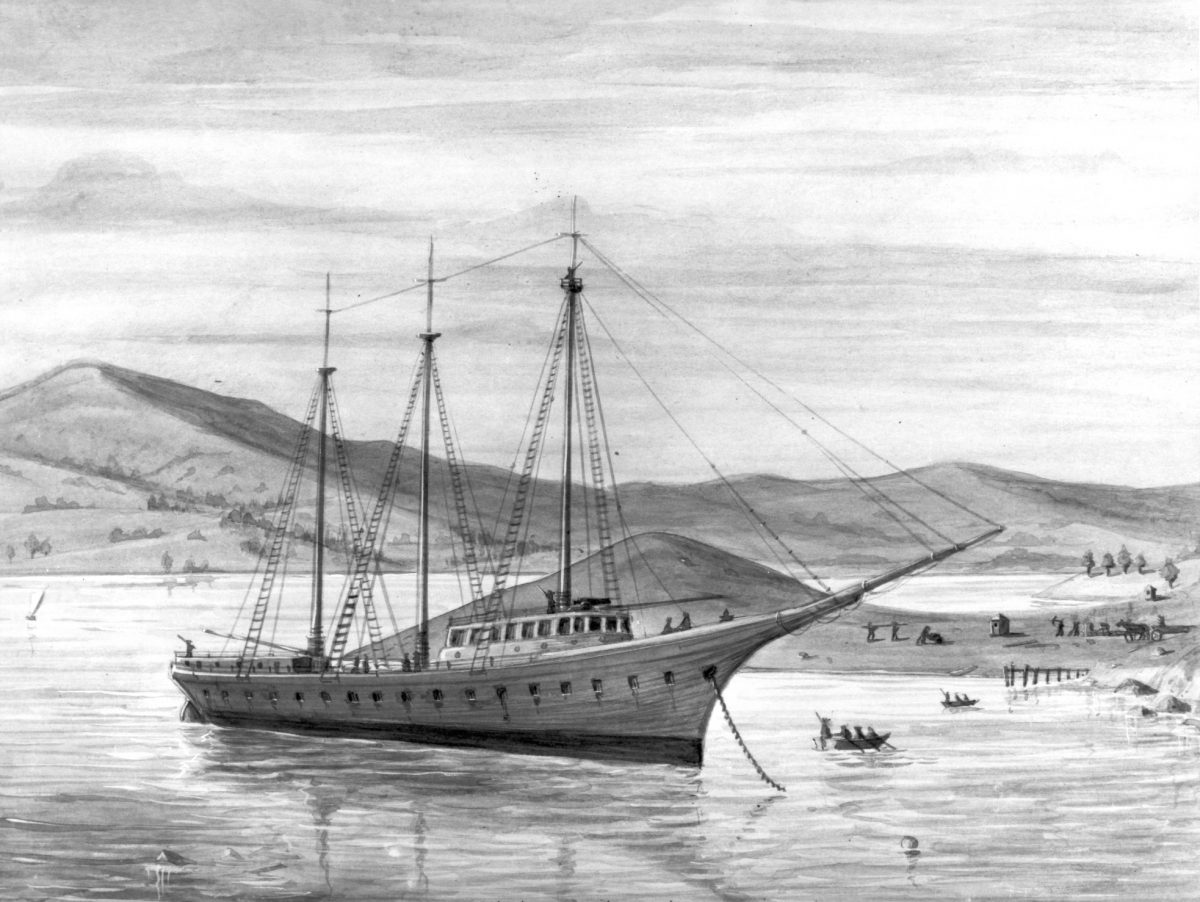

Terminal Island returns to prison roots

Terminal Island started as a federal prison before becoming a Navy facility. When the state began housing inmates there in 1950, it marked a return to the facility’s roots.

“The fortress-like reinforced-concrete structures … were erected in 1938 as a federal prison,” reported the News-Pilot newspaper on April 5, 1951. “Al Capone … was confined there for a time. The U.S. Navy took over the buildings in 1942.”

For the state to make use of Terminal Island, in 1944 state corrections director Richard A. McGee traveled to Washington, D.C., to make a presentation to the Pentagon.

“The state plans to use the facility (at Terminal Island) until it builds a new general hospital on a 900-acre site near Vacaville,” the newspaper reported.

The Long Beach Press Telegram dated June 2, 1950, reported on the preparations to transfer the facility.

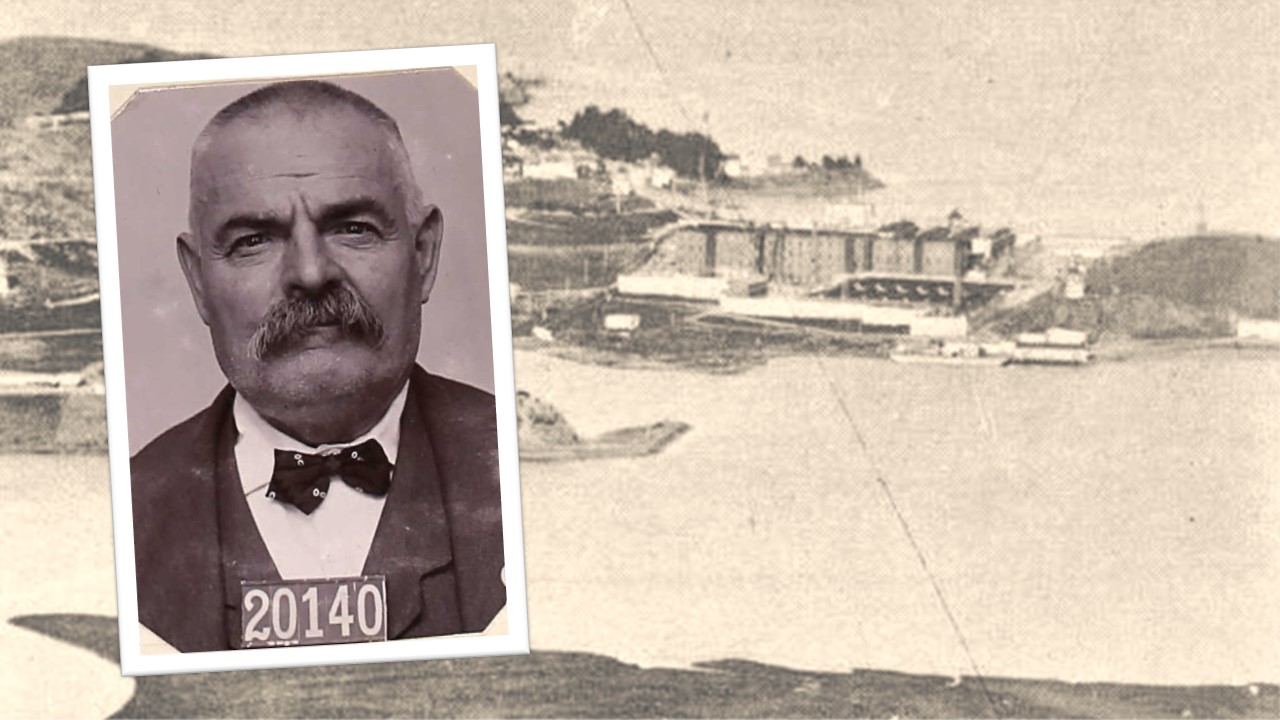

First superintendent appointed

Dr. Marion King was appointed as CMF’s first superintendent. King had previously served as medical director of the federal bureau of prisons.

“Dr. Marion R. King … (inspected) the Naval Disciplinary Barracks at Terminal Island which he is to be in charge of when it becomes a hospital for convicted sex offenders on July 1,” the paper reported. “Showing him (around) the former federal prison (was) Lt. Commander Donald A. Gary, commanding officer of the barracks.”

On June 30, 1950, San Quentin State Prison transferred 65 inmates to Terminal Island. Their job was to help prepare the facility for the state.

“The transformation of the Long Beach Naval Disciplinary Barracks on Terminal Island took only 24 hours to complete,” according to a CMF history document prepared by Office Technician Alice Trevino in 2005.

On July 1, 1950, the Los Angeles Times reported on the transition.

“The U.S. Navy in a brief ceremony yesterday closed its disciplinary barracks at Terminal Island. Keys to the huge gray prison structure were turned over to Dr. Marion King,” the Times reported. “Built 12 years ago, the new state prison for sex offenders began the fourth phase in its history. Originally built as a U.S. corrections institution, it later became a Navy receiving station, then a Naval disciplinary barracks. King announced that the first group of prisoners and patients will be brought to the facility about July 10. He and a skeleton staff have been at the institution for the past month and 65 trustees arrived yesterday to start preparation for receiving prisoners.”

CMF picks up and moves to Vacaville

Construction of the permanent facility at Vacaville began in 1952.

In 1953, the state began ramping up to hire new Correctional Officers.

“The State Personnel Board has set July 18 as the examining date for candidates wanting guard positions at Folsom, San Quentin, Soledad, Terminal Island and Tracy state prisons,” reported the Lodi News-Sentinel on May 28, 1953. “The job pays from $295 to $358 a month.”

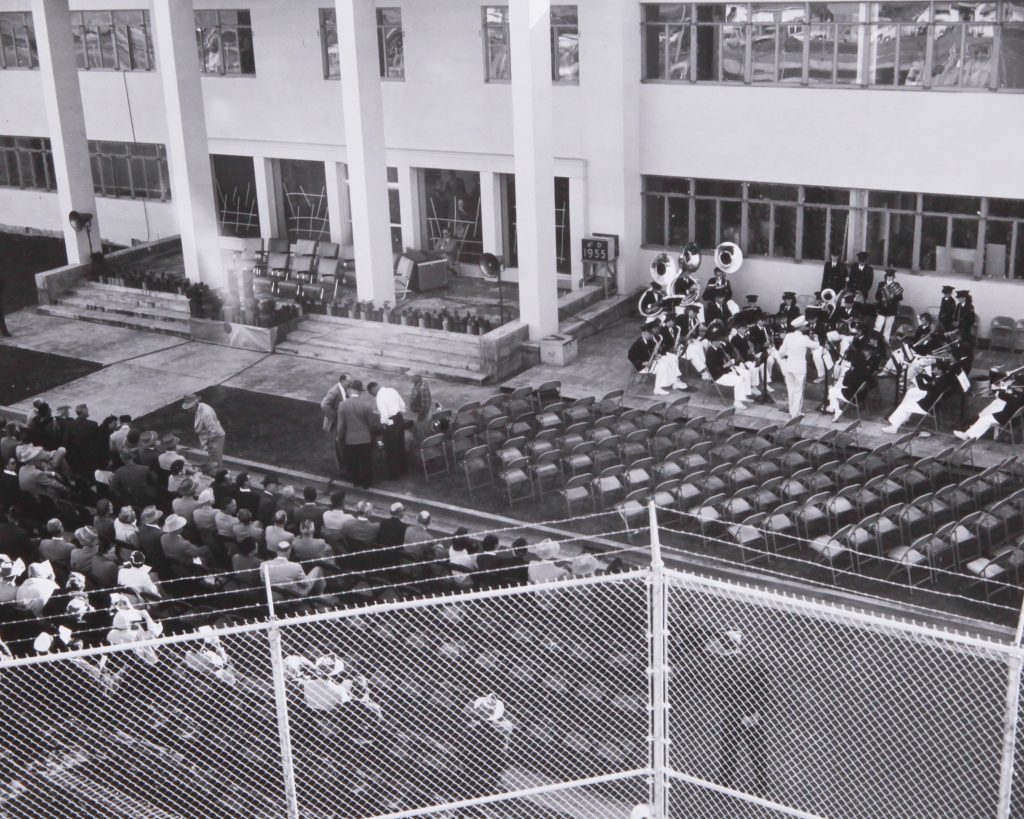

On Oct. 26, 1954, CMF was officially dedicated. Richard A. McGee, Director of Corrections, and Gov. Goodwin Knight attended the ceremony. The Governor laid the cornerstone.

On Oct. 30, 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren toured the new facility. The former Governor told the Vacaville Reporter, CMF was one of his pet projects for the “state’s mentally or emotionally ill prisoners.” According to the newspaper, CMF was the first institutional prison-hospital in the nation.

“The gigantic task of moving prisoners and personnel from Terminal Island in southern California will be completed when the last group of some 500 inmates arrives (by) bus,” reported the Vallejo Times-Herald on May 9, 1955.

“King is a psychiatrist as well as a prison administrator. He saw the institution he headed at Terminal Island become the birthplace five years ago of group therapy for rehabilitation. It is believed to be one of the most effective psychiatric devices currently used to further the progressive concept of prisoner treatment rather than mere custody,” the newspaper reported.

On April 6, 1955, the first inmates arrived at the new CMF. Within the facility’s first year of operation, an estimated 1,300 inmates were transferred from other institutions.

Rehabilitation of body and mind

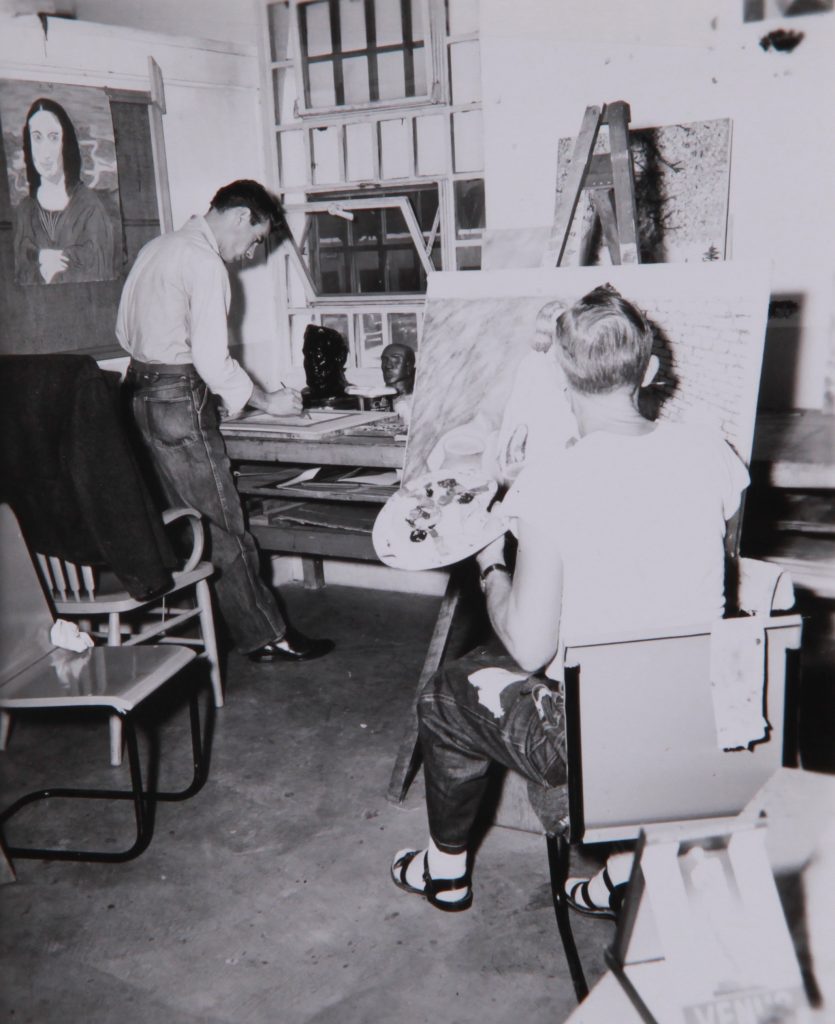

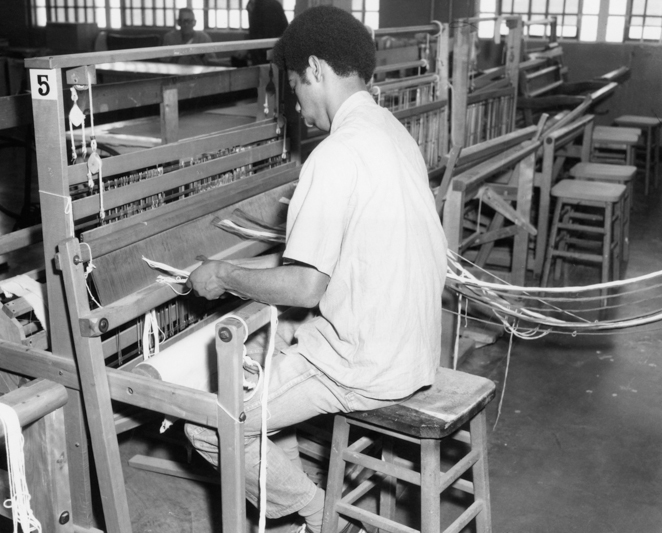

“Any of the … inmates at the state’s sprawling psychiatric treatment center (in Vacaville) can learn to be artists, musicians, singers, actors or polished speakers,” reported the Gettysburg Times on Nov. 6, 1964. “For those not inclined toward the arts, there are baseball teams, game breeding farm, … schools … and a factory for making braille books. Department officials say other California prisons carry on some of these programs, but none are so extensive as those at Vacaville.”

Dr. William C. Keating, superintendent of CMF, told the paper he believed finding uses for spare time was key to rehabilitating inmates.

“The 43-year-old former head of California’s Sonoma State Hospital believes most people fail in life because ‘they don’t know how to use their free time (and failed) to develop a meaningful avocation,’” the newspaper reported. Superintendent Keating had been in his position for four years by 1964.

“Our job is to rehabilitate people … the rehabilitation is not done to the environment to which the individual must return,” Keating told the newspaper. “Prison need not be an end, but can sometimes mean a new beginning.”

California Medical Facility’s first Fire Chief

Correctional Officer Walt Bernhardt arrived two months prior to CMF opening in Vacaville.

“His initial duties included everything from bolting bunks onto walls to assembling kitchen tables,” a 2005 CMF document states. “As a Third Watch CO, he subsequently escorted the first busload of prisoners into the new facility in 1955.”

In 1964, Sgt. Bernhardt took command of the CMF Fire Department. At the time, it was standard for sergeants to regularly rotate to the position of fire chief. Two years later, he was officially reclassified as the first CMF Fire Chief. Working with the State Assembly, Chief Bernhardt helped negotiate regulations to enable CMF firefighters to take their place alongside regular county fire crews whenever needed through a mutual aid assistance plan.

Richard McGee credits military captain for idea

In 1975, Dr. Marion King and Richard McGee walked into CMF again to mark 25 years since the founding of the temporary facility at Terminal Island.

McGee was a featured speaker. Luckily, CMF preserved a copy of his written speech.

“I think about 1947, it became apparent the U.S. Bureau of Prisons wanted to get (Terminal Island) back but they didn’t have any money and they didn’t have enough prisoners either at that time. I went back to Washington to try to capture that institution for state use. (At) the Pentagon, I was told there was no chance.

“So I gave up (and) walked out to the front of the Pentagon. A young captain walked up behind me and said, ‘There was a way you could get that, you know, if you want to. The government will turn it over to you if you use it as a hospital but (not) as a prison.’”

McGee told the gathering if he’d been successful in his first bid, CMF might never have come to fruition.

“So that young captain, who never told me his name, is responsible for the medical facility being where it was at Terminal Island,” he said. “That is how it all got started.”

Superintendent T.L. Clanon said CMF was different from its very beginning.

“It seems to me the philosophy active in founding this institution and has been productive is not the idea that prisoners have some common problem we are going to cure, but the idea that they all have a common humanity that we’ve got to deal with,” he said.

Singing cowboy serves time at CMF

Donnell “Spade” Cooley gained fame in the early days of television as the King of Western Swing. One of his hits was “Shame, Shame on You.”

His career started in 1934 when he headed to Hollywood working as a musician at “barn dances and hillbilly clubs,” according to reports.

In 1937, Republic Pictures hired him because he resembled Roy Rogers, standing in for Rogers on several films. When Rogers discovered Cooley could play violin, he hired him for his touring band.

In the 1940s, he married singer Ella Mae Evans and formed his own band, the Western Dance Gang.

Cooley became a TV sensation in the early 1950s but gave up his career to focus on a 1,000-acre amusement center in Kern County.

On April 3, 1961, his wife’s battered body was found in their ranch home. Cooley was convicted of her murder and was sentenced to life in prison. A heart condition landed him at California Medical Facility in Vacaville.

Nine years later, he was looking at release from prison.

“Spade Cooley, who reigned over the world of country music 20 years ago as the ‘King of Western Swing,’ will be released from prison Feb. 22, 1970, after almost nine years behind bars for killing his wife,” reported the Desert Sun on Aug. 6, 1969. “The State Adult Authority voted unanimously to release Cooley.”

In 1969, at age 59 and just three months shy of his scheduled release, Cooley agreed to perform a benefit show for the Alameda County Sheriffs Association.

“(He) collapsed during an intermission after receiving a standing ovation for his performance,” reported the Desert Sun, Nov. 24, 1969. He died at the show.

Superintendents/Wardens

- 1950-59 Marion King

- 1960-66 William Keating

- 1966-1972 L.J. Pope

- 1972-1981 Thomas Clanon

- 1981-82 Jesus Marquez

- 1982-1992 Eddie Ylst

- 1992-1993 George Ingle

- 1993-1996 Mike Pickett

- 1996-2003 Ana Ramirez

- 2003-05 Teresa Schwartz

- 2007-08 Mike Knowles

- 2008-11 Kathleen Dickinson

- 2011-12 Vimal J. Singh

- 2012-14 Brian Duffy

- 2014-current Robert Fox

Timeline

- 1938 Federal prison built at Terminal Island.

- 1942 US Navy began using Terminal Island.

- June 30, 1950 First 65 inmates from San Quentin arrived at Terminal Island near Los Angeles to convert old Naval disciplinary barracks into the first California Medical Facility.

- July 1, 1950 Keys to Terminal Island facility turned over to CMF superintendent Marion King.

- 1952 CMF construction began in Vacaville.

- Oct. 26, 1954 CMF in Vacaville dedicated.

- April 6, 1955 First inmates arrived at the new CMF.

- 1957 CMF Reception-Guidance Center opened.

- 1973 First female correctional officers joined staff at CMF.

- June 10, 1984 Ray Charles was first major entertainer to perform at CMF.

- Nov. 27, 1984 Gov. George Deukmejian dedicated California Medical Facility-South (which later became CSP-Solano)

- 1992 CSP-Solano officially separated from CMF

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Photos compiled by Eric Owens, CDCR photographer

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.

Explore CDCR history

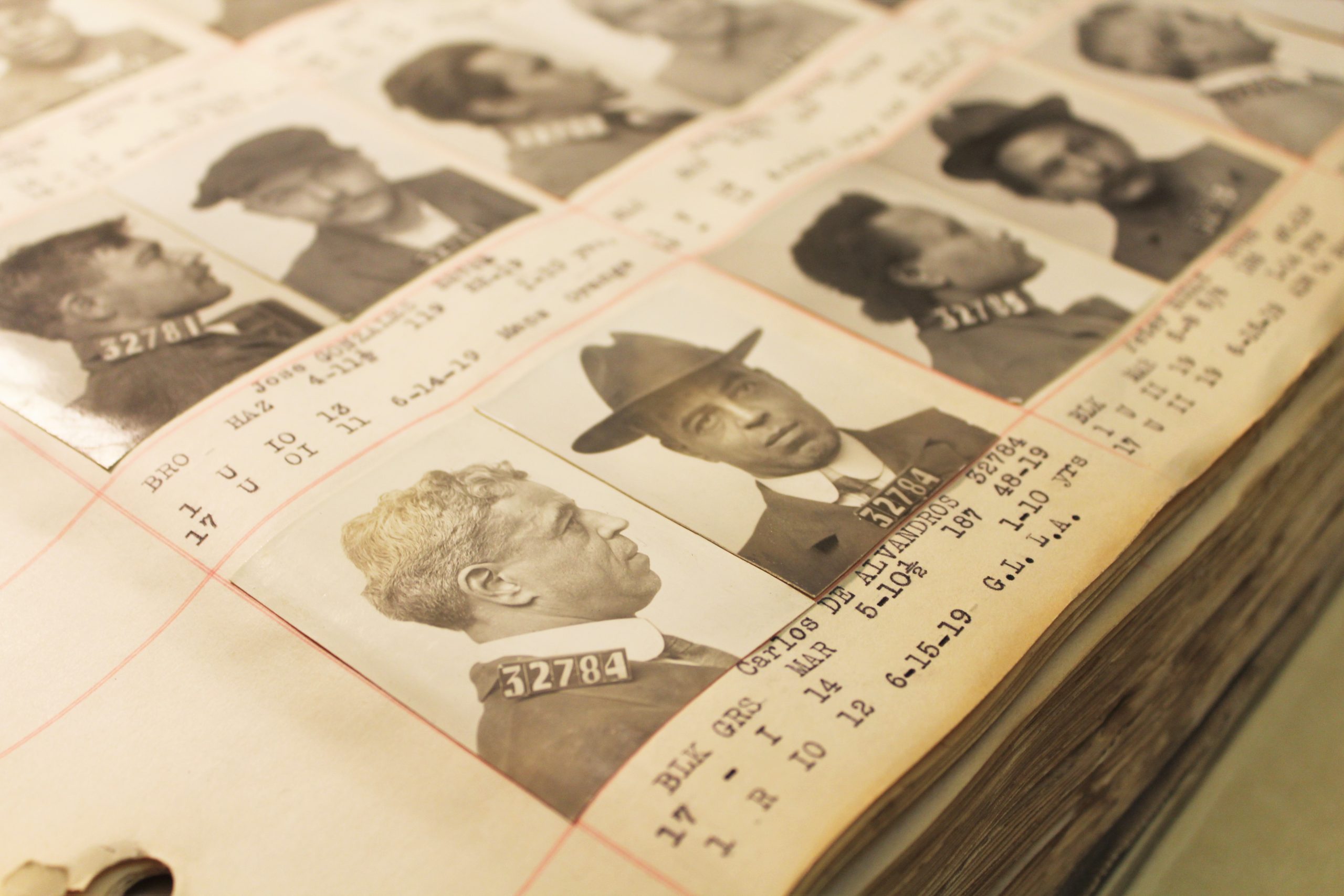

San Quentin and the case of the clairvoyant crime ring

A tale of confidence men, swindlers, and a clairvoyant crime ring are part of the historical fabric of San Quentin. One early 1900s case involved clairvoyants, fraudulent sales of radium mining stock, and tall tales told by a smooth-talking mystic.

California prisons have long celebrated Easter

Celebratory events marking Easter have long played a rehabilitative role in California prisons to help reentry efforts.

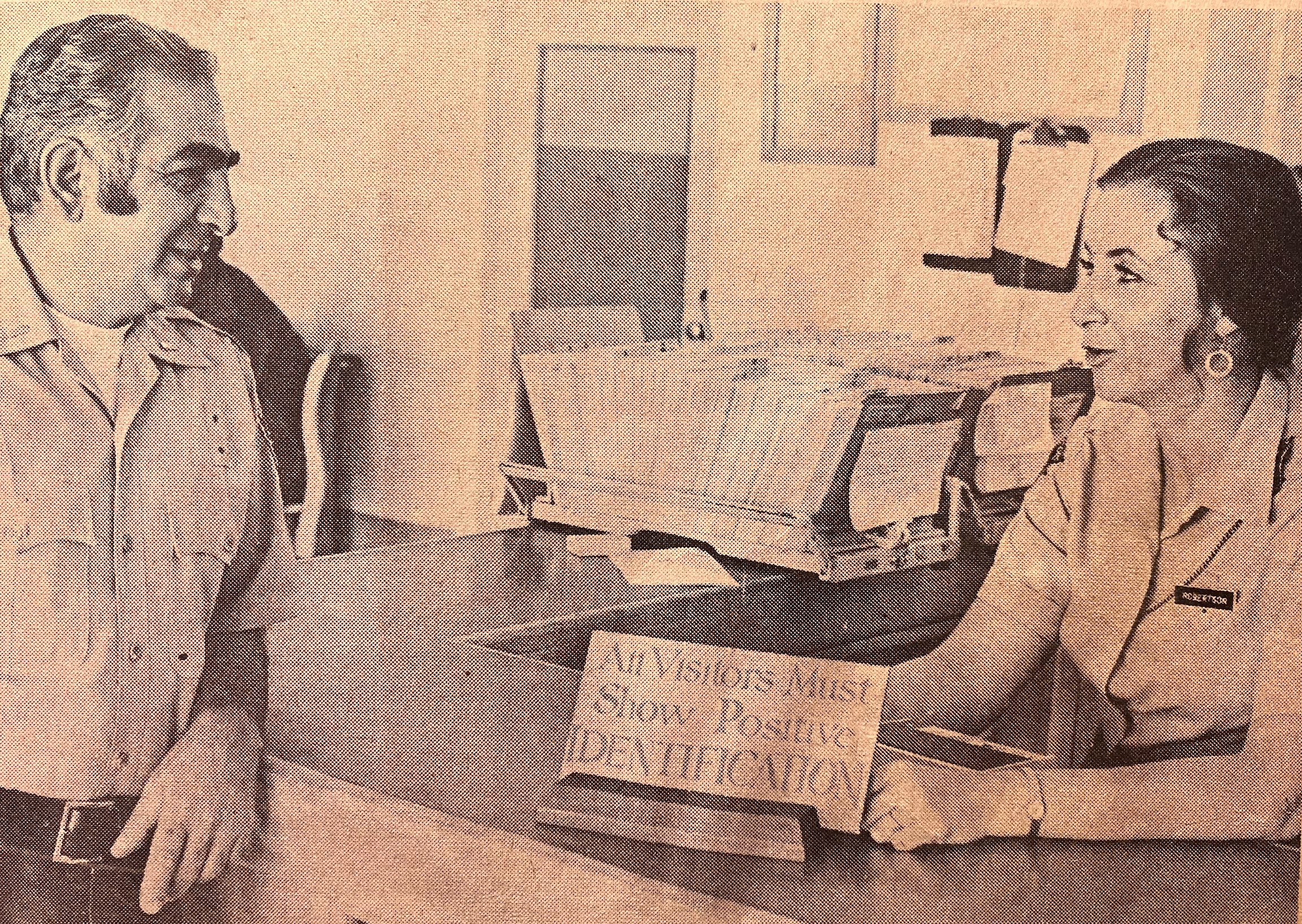

1973: DVI’s first female officer reports for duty

On June 4, 1973, Trella Robertson was hired as the first female correctional officer at Deuel Vocational Institution (DVI) in Tracy.

San Quentin evolution through the years

San Quentin Rehabilitation Center was California’s first institution to incarcerate those who’ve been convicted of breaking laws.

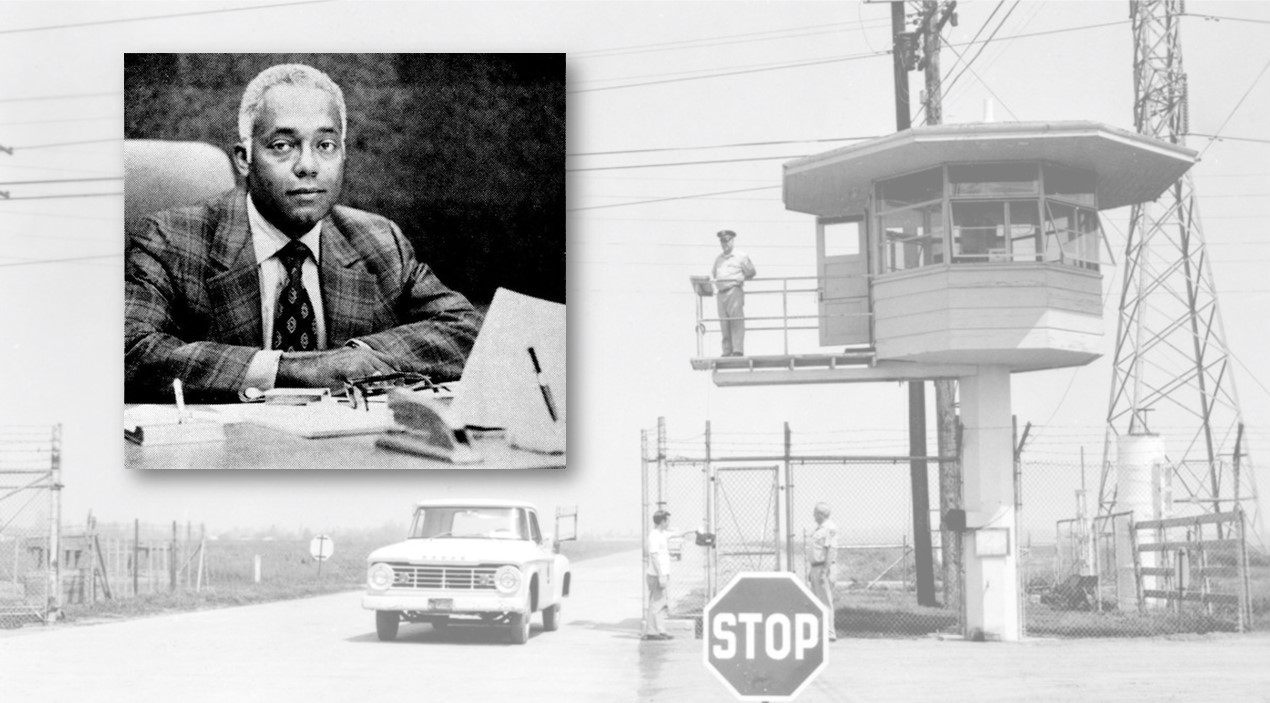

1971: Griggs was first black warden

In honor of Black History Month, Inside CDCR looks at the career of California’s first black parole administrator and prison warden: Bertram Griggs.

Seppi family seeks 1903 San Quentin details

Descendants of Frank Seppi, incarcerated at San Quentin State Prison in 1903, recently contacted the prison museum to learn more details.