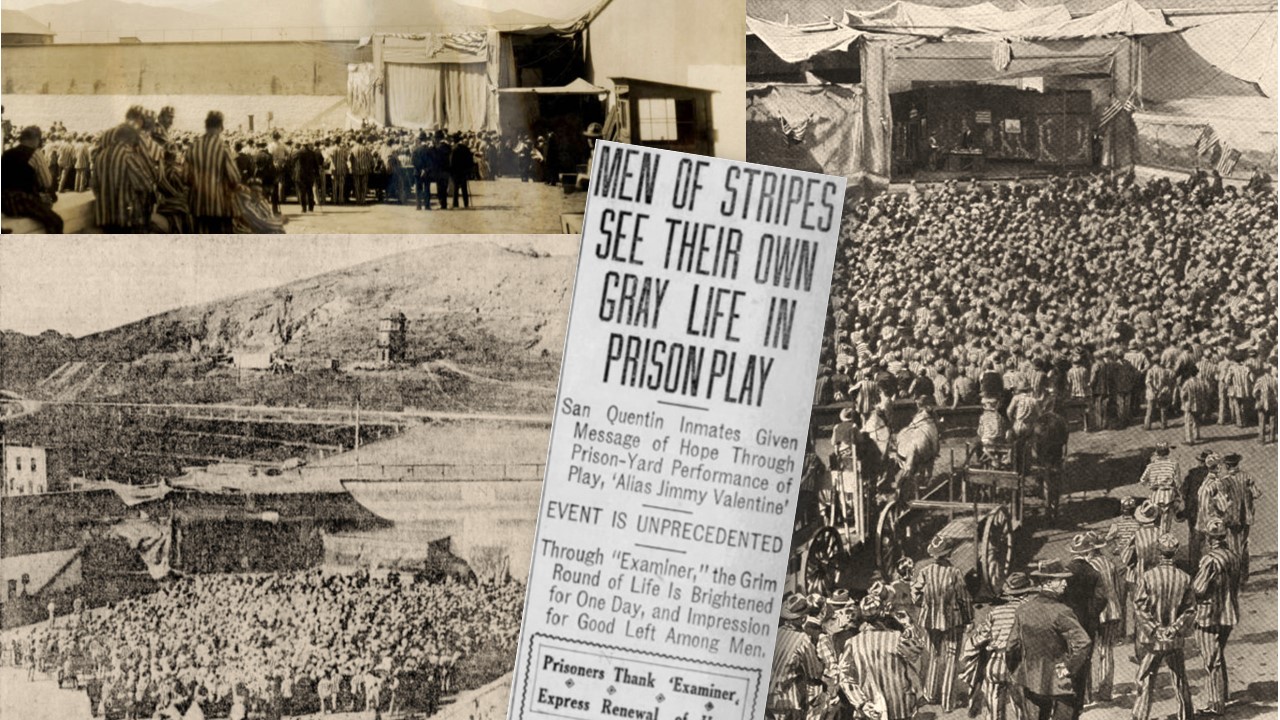

Art as rehabilitation dates to 1911, when the warden partnered with public organizations and local media to offer a play inside San Quentin. The groundbreaking effort marked the first time the incarcerated were entertained by an outside theatrical group.

Play is turning point for arts rehabilitation

Based on the O. Henry penned short story “A Retrieved Reformation,” theatrical producers saw dramatic potential and gave it the stage treatment. The play, “Alias Jimmy Valentine,” became a hit and toured across North America.

At about the same time, Warden John Hoyle began implementing a number of reforms. The play’s strong message of hope, reformation and second-chances made it the ideal candidate for a daring experiment, as newspapers called it in 1911.

Fostering second chances

Warden Hoyle saw the effort to produce the play in prison as a turning point in public perception regarding rehabilitation.

Much like modern media-outreach efforts, Hoyle sought their help. He worked with the San Francisco Examiner, eventually getting them to help sponsor the event. To prepare, he put the incarcerated population to work building a stage as well as printing a program. Hoyle also enlisted the help of a local steamer captain.

“Two thousand convicts, sitting in striped garb, saw the general story of their lives mirrored in (the drama performed) in San Quentin. (After the play,) 2,000 men went to their cells, (thinking) what might have been and what is to be. Pictured before them (was) the life of Jimmy Valentine, the safe robber pardoned from Sing Sing, resolved to ‘turn square,’ and did so against tremendous odds,” reported the Mariposa Gazette, Oct. 14, 1911.

“They cheered Jimmy for his determination to lead a clean life. They admired his grit and they gloried in his achievement. The stage was set in the lower yard, out in the open, in the shadow of the old sash and blind factory, where the condemned cell and the execution room are located. It was improvised by the convicts under the direction of Albert Cowles, stage director of the Cort Theater in San Francisco, where the drama of convict life was being presented. Henry Noel, a prisoner, led the convict orchestra. Theodore Dougherty, another convict, printed the programs, distributed them and assisted the guards in the seating of the prisoners.”

Play offers story of hope

According to a story published Oct. 5, 1911, in the Marin Journal, “The principal character of ‘Alias Jimmy Valentine’ is a man who began life wrong. For his offenses against the law, he became a convict. The play traces his evolution from a career of crime to one of honesty and well-doing, and is a powerful argument against the entrenched theory that there is no chance for the man who has been in prison. The hope is that the play may have a good effect on convicts.”

There were some influential people in the audience including:

- wife of Governor Hiram Johnson

- Dennis Duffy, state prison commission member

- Dr. Wade Stone, prison physician

- Mark Noon, parole board clerk, and his wife.

Nearly two dozen reporters were also on hand to witness the play and document inmate reaction. Warden Hoyle kept the production on track.

“Work was suspended at noon and the play began at 12:30 o’clock. Three hours later, the final curtain closed,” reported the San Francisco Call, Oct. 6, 1911. “H.B. Warner, star of the play, won the hearts of the prisoners. They cheered him and waved their hats to him in a splendid ovation. (After the play), George Clark, a forger, presented him with a resolution adopted by the convicts expressing thanks.”

Actor thanks incarcerated audience

“I never played to a more intelligent or responsive audience in my life,” Warner said. “I saw many a tear glisten in the sunlight when some of those little sermons of the play were recited in the lines.”

Phyllis Sherwood, who played the female lead, “will forever more be the patron saint of the prisoners. She endeared herself to every one of them yesterday. Alma Sedley and Phillip Traub, the two children who played the juvenile parts, struck a chord in the big audience that proves more conclusively than the finding of all the studious criminologists and penologists that convicts have hearts.”

Warden Hoyle was grateful for all the help in making the project happen. Capt. William Leale, of the steamer Caroline, shuttled actors, audience members and stage props to the prison, free of charge.

“This performance today is a great thing for the prison,” Hoyle said at the time. “It marks a new era in the public attitude toward convicts. (The effort) shows the prisoners, as nothing else could do, that the community has encouragement for them. (It will) make society realize that it owes a debt of humanity to (those) who are confined within prison walls. It will help remove the idea of punishment as the purpose of imprisonment and substitute the idea of the higher purpose of correction. We want prisoners to know, as this play points out, that a convict who tries to reform will be given a chance and encouragement to work out his regeneration.”

Three paroled shortly after play

As a form of an early effort at medical parole, perhaps sparked by the play, the prison paroled some long-held convicts shortly after the performance.

“At sunrise tomorrow morning the prison gates of San Quentin penitentiary will open for a man and woman who have been inside the institution longer than any others there, and for an old Indian chief who is nearly blind,” reported the San Francisco Call, Dec. 16, 1911. “Charles Thorne, (aka Charley Dorsey,) who has been under sentence of life imprisonment for murder in Nevada County, will be released. He was received at the prison March 15, 1883. He has served five terms, the last one for slaying a man in holding up a stage in the mountains. On account of his age of late years he has acted as guide to visitors in the execution room.”

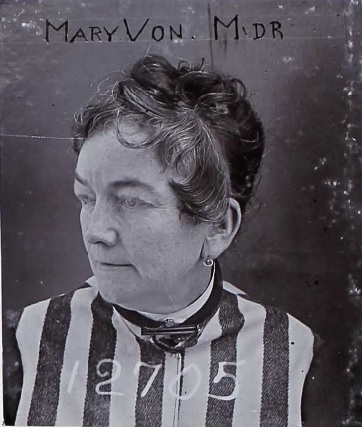

Another was Mary Von, convicted for murdering her husband when she discovered he had a secret second wife.

“She has been in the penitentiary since Oct.18, 1887, when she was received from Los Angeles,” the paper reported. “She is regarded as peculiar at the prison and it is said, when ‘Alias Jimmy Valentine’ was played at the prison, she refused to witness it. … Both have been paroled by the state board of prison directors.”

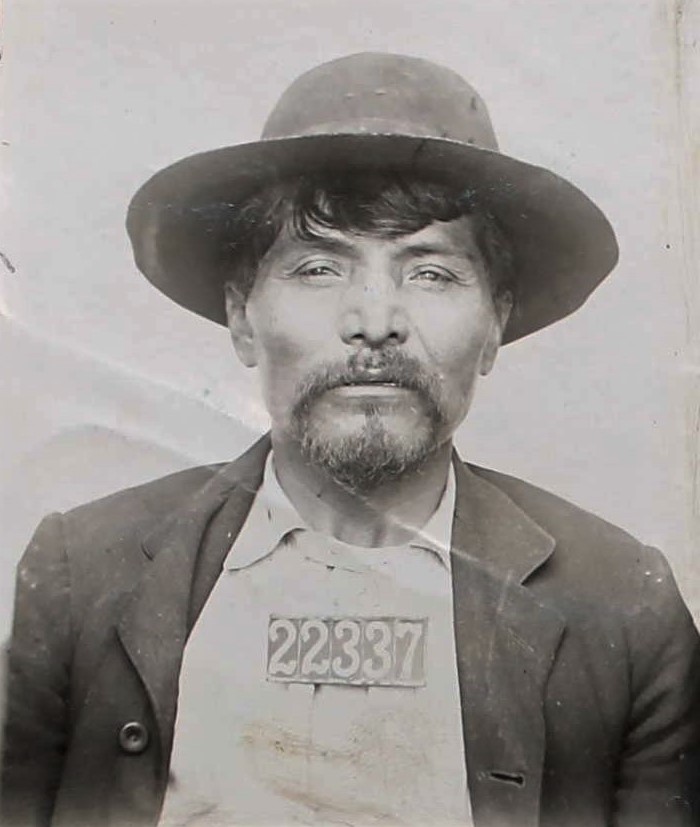

The directors also paroled the former chief of the Modoc tribe, “Old Jim” Forrest, in 1913.

“Through the efforts of Rev. P. Collopy and a number of others, he was paroled to rejoin his tribe. ‘Old Jim’ is white haired and 65 years old,” reported the paper.

Forrest was received at San Quentin in September 1907 to serve nine years for manslaughter.

‘Old-fashioned doctrine of reform’

The actor in the title role of Valentine said he believed in giving people a chance to make an honest living after paying their debts to society.

“I am a firm believer in the (rehabilitation) of man because I have an uncomfortable feeling that there is something of the criminal in all of us. Not all of the meanness in man is punishable by fines and imprisonment and there are free men walking the streets of respectability who, if punishment always fit the crime, would be (in prison). I believe in the old-fashioned doctrine of reform,” Warner told the San Francisco Call, Oct. 8, 1911. “Many do not and many men do not want to reform. Perhaps the man with a genius of forgery or safe opening is hardest of all to set straight, but it is a pleasing thought for me to entertain (the notion) that men may reform.”

The play’s rehabilitative effects on San Quentin were obvious, according to prison officials who said they had no problems with inmates for weeks after the production.

Parolees given chance to see play

Through a charitable organization, the program was expanded beyond prison walls in 1912 to give parolees a chance to view the production, hoping to inspire them to continue on a positive path.

“Advocates of prison reform promise to be in force this evening at the Alcazar, where Richard Bennett, Mabel Morrison and the regular stock company will present the detective-thief play, ‘Alias Jimmy Valentine,’ for the benefit of the Mutual Aid and Employment bureau’s fund to help pardoned and paroled convicts. No more appropriate play could be selected for the purpose of acquainting the public with the obstacles and temptations encountered by the man who steps out of the penitentiary (determined) to lead an honest life, for such a man is the principal figure in the cast,” reported the San Francisco Call, May 22, 1912.

“Alias Jimmy Valentine,” a play about a paroled offender trying to turn his life around, made it possible for other programs to follow. Theater and arts eventually became recognized rehabilitative tools for the state prison system.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Office of Public and Employee Communications

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.