(Editor’s Note: There are many differing accounts related to Rattlesnake Dick, aka Richard Barter, his life and how he became involved in crime. This research-based article pulls from many sources including California State Archives, Placer County Museums, books, magazines and newspaper articles.)

The legend of Gold Rush era bandit Rattlesnake Dick, aka Richard Barter, is full of speculation and guesswork.

In one version, Barter is the son of a British military officer in Canada. After his parents died, Barter struck out for California, hoping to support his sister. Instead, he ran headfirst into trouble and prison.

In the mid-1850s, San Quentin hadn’t enacted a classification system to keep younger first-time offenders away from hardened criminals. Early wardens called for just such a system but the relatively new prison didn’t have the resources or space, according to rebuttals at the time. Barter’s story, a blend of fiction sprinkled with facts, highlights the need for classification.

San Quentin, Tom Bell and Rattlesnake Dick

While incarcerated in San Quentin, a 20-year-old Barter met outlaw gang leader Tom Bell. After his release, Barter threw his lot in with Bell’s gang. According to prison records at California State Archives, Barter was received by San Quentin State Prison on Dec. 20, 1854, to serve a sentence for grand larceny.

The need for classification was emphasized in reports for decades after Barter served his time at San Quentin.

In 1880, the Prison Board of Directors wrote, “It necessarily brings the younger and less criminal class in daily contact and association with the vilest and most degraded elements of criminal life, thereby destroying more effectually any good qualities that may remain, without in the slightest degree redeeming the utterly vicious. … This sort of association is doubtless the cause of hundreds of returns to prison, and, of course, the commission of hundreds of crimes. This vice, for such it is, in our penal system, may doubtless be greatly diminished, if not altogether remedied, by a classification of prisoners.”

The 1903 State Board of Charities and Corrections again reiterated the need to separate hardened criminals from the younger element.

“This matter has been referred to and elaborated upon again and again in the later reports of the Prison Directors as being one of the greatest defects in our prisons. The steady increase in our prison population is constantly aggravating this already bad situation. It is no exaggeration to say that our State prisons in their present condition are simply schools for crime,” they wrote.

Classification of prisoners didn’t become standard practice until San Quentin Warden John Hoyle introduced numerous reforms between 1907 and 1913.

If a classification system had been in place, young Richard Barter may have taken a different path.

Good intentions, poor choices and bad luck

The California Gold Rush drew Barter, 17, and his brother to seek their fortunes in 1850.

With their parents dead, it was up to the two brothers to earn a living and support their sister, who stayed behind.

They settled in Rattlesnake Bar on the North Fork of the American River between Auburn and Folsom. The brothers had a tough time of it in the mining business and with supplies running low, the older brother decided to return home. Barter, despite his youth, was determined to continue working the claim. Aside from his own claim, Barter also worked for other miners for extra cash.

After a dispute, a neighboring miner claimed Barter stole clothing. Even though he was cleared of the charges, other miners began distrusting him, causing him to lose jobs.

His first brush with the law behind him, he focused on mining.

Another allegation lands Barter in prison

Soon, another neighbor accused Barter of stealing a mule. Claiming he didn’t steal the animal, he admitted to knowing who was responsible, but refused to give authorities the name. He was arrested, convicted, and sent to San Quentin for two years.

After serving a year of his sentence, evidence surfaced proving his innocence, according to “The History of Placer County,” published in 1882.

He was released from prison, but gave up on his dream of mining at Rattlesnake Bar. Instead, he headed to Shasta County for a fresh start.

He worked for others, and did a little prospecting on his own. He wasn’t striking it rich but was able to make ends meet, according to “Bad Company: The Story of California’s Legendary and Actual Stage-Robbers” by Joseph Henry Jackson.

The peace of a new identity and a new place didn’t last long. Soon a former Rattlesnake Bar miner made his way through Shasta County, recognized Barter, and informed the residents about the “horse thief” they had in their midst.

Frustrated and angry, finding himself unable to find work once again, Barter decided to live up to his reputation. Inexperienced in such matters, Barter knew where to turn thanks to his time in San Quentin.

Hodges and Barter do time in San Quentin

Jackson’s book claims there are no records to indicate Barter served time in state prison but the official San Quentin inmate register shows 20-year-old Richard Barter, inmate number 516, was received Dec. 20, 1854 and discharged Dec. 18, 1855.

According to most accounts, this is where he met 25-year-old outlaw Tom Bell, whose real name was Thomas “Doc” Hodges.

According to state records, Thomas Hodges escaped twice.

On Oct. 8, 1851, he was received at San Francisco County Jail under Sheriff Jack Hayes. (Editor’s note: County jails served as the first state prisons.) He escaped but was recaptured in 1852 by Gen. James Estill, who held the contract to run the state prison at the time.

On March 2, 1853, Hodges was received at San Quentin and given the number 170. Serving 10 years for grand larceny, Hodges escaped May 12, 1855, according to records.

First stagecoach robbery

After he was released, Barter began riding with Hodges and his gang.

Their first stagecoach robbery was Aug. 11, 1856, but well-armed stagecoach guards drove them away. One person, the wife of a popular Marysville barber, was killed during the attempted robbery.

A defiant Hodges, aka Bell, wrote a five-word letter to the newspaper: “Catch me if you can.” Some historians claim this was the first true stagecoach robbery in the west.

Posses were formed and sent to track down the gang. Realizing they were being pursued, the bandits split up.

Hodges was eventually tracked down to a secluded camp near the San Joaquin River. He was hanged by a vigilante group on Oct. 4, 1856.

With their leader dead, Barter assumed control. He started robbing stagecoaches in Shasta County but eventually moved operations to Folsom. Here, he based the gang out of his old mining camp at Rattlesnake Bar.

Holding a grudge against the placer miners, he targeted them as well. For a few years, Barter and his gang terrorized the region, but Placer County Deputy Sheriff John Boggs was on the case.

Boggs pursued the gang, targeting Barter in particular, repeatedly arresting the young gang leader. Barter was never behind bars for long, usually escaping the jail within days.

Rattlesnake Dick doesn’t hide

Barter’s luck ran out in July 1859 when he and partner David Beaver traveled along a main roadway in Auburn.

Recognizing Barter, a town resident ran to warn George M. Martin, county tax collector and deputy sheriff. Quicky, Martin rounded up a posse with deputies William Crutcher and George Johnston. Believing they didn’t have enough time to gather more men, they set off to capture Barter.

They ran into the highwaymen near the Auburn railroad station. Johnston, who was familiar with Barter from past run-ins, rode alongside him, ordering the bandits to surrender. Barter replied by drawing his pistol and opening fire, striking Johnston’s hand, blowing off a finger. But Johnston and Barter had fired simultaneously, according to reports, with Johnston’s bullet passing through Barter’s chest.

Barter and his companion continued firing as they fled. Their bullets struck Martin, who fell from his horse. The deputy was dead.

The end for Rattlesnake Dick

About a mile from the scene of the gunfight, a gravely wounded Barter dismounted his horse and penned a quick note.

“Rattlesnake Dick dies but never surrenders, as all true Britons do,” he wrote. “If J. Boggs is dead, I am satisfied.”

In the confusion and darkness, Barter mistakenly believed Martin to be Boggs.

Some reports claim Barter asked Beaver to do him in and finish the job. The official report is he was found with a self-inflicted bullet wound through the head, one hand clutching his gun while the other clutched the note. His body was found the following morning alongside the road, covered with a horse blanket. A few days later, Barter’s horse was found wandering near Grass Valley. The horse appeared to have a gunshot wound near its neck.

Man charged with Barter’s death

Long after Barter’s death, many continued to be associated with the notorious bandit.

His partner on that fateful night, David Beaver, aka David Weaver, fled but was arrested after an 1860 altercation with a man in San Luis Obispo. Beaver was going by the name Alex Wright and was sent to San Quentin for 10 years. When he was released after serving nine, authorities were waiting for him. They ended up charging him with Barter’s murder. According to authorities, Rattlesnake Dick didn’t shoot himself in the head, but instead Beaver had done the deed.

“Sheriff Neff of Placer County lodged in the station house David Weaver, aka Alex Wright. This man is to be taken to Auburn, Placer County, and tried on an indictment found March 5, 1869, by the Grand Jury of that county, charging him with the murder of a man known as Rattlesnake Dick in 1859,” reported the Daily Alta California, May 27, 1869. According to authorities, Weaver pulled the trigger that ended Barter’s life.

“When two miles away from the place of encounter (in 1859), Rattlesnake Dick, who was somewhat injured and fatigued, was unable to go any further. (He) was then shot and killed by Wright,” the newspaper reported regarding the allegations. Weaver’s case appears to have been dropped.

The lawmen after Barter

William Crutcher passed away in 1896. “W.M. Crutcher, Internal Revenue Officer and Collector, died at his home in (Auburn on March 6) from a paralytic stroke received two weeks ago,” reported the Grass Valley Morning Union, March 17, 1896. “He was thrice Under Sheriff of Placer County and while holding the office distinguished himself as one of those who captured and overthrew the famous Rattlesnake Dick gang of outlaws. Mr. Crutcher represented his county in the legislature and also served as sergeant-at-arms of the lower branch of that body. … Deceased was a native of Kentucky, aged 67 years.”

George Johnston enjoyed a long career in mining. “Johnston, who is engaged in the mining department of the Risdon Iron Works and is one of the oldest mining men in the country, today celebrates his 80th birthday,” reported the San Francisco Call, Jan. 31, 1905. “In spite of his years, Mr. Johnston puts in a full day at (work) six times a week and is younger in energy than many men of half his years. From 1855 to 1861 he was Under Sheriff of Placer County and killed the notorious outlaw Rattlesnake Dick in Auburn.”

Boggs elected sheriff

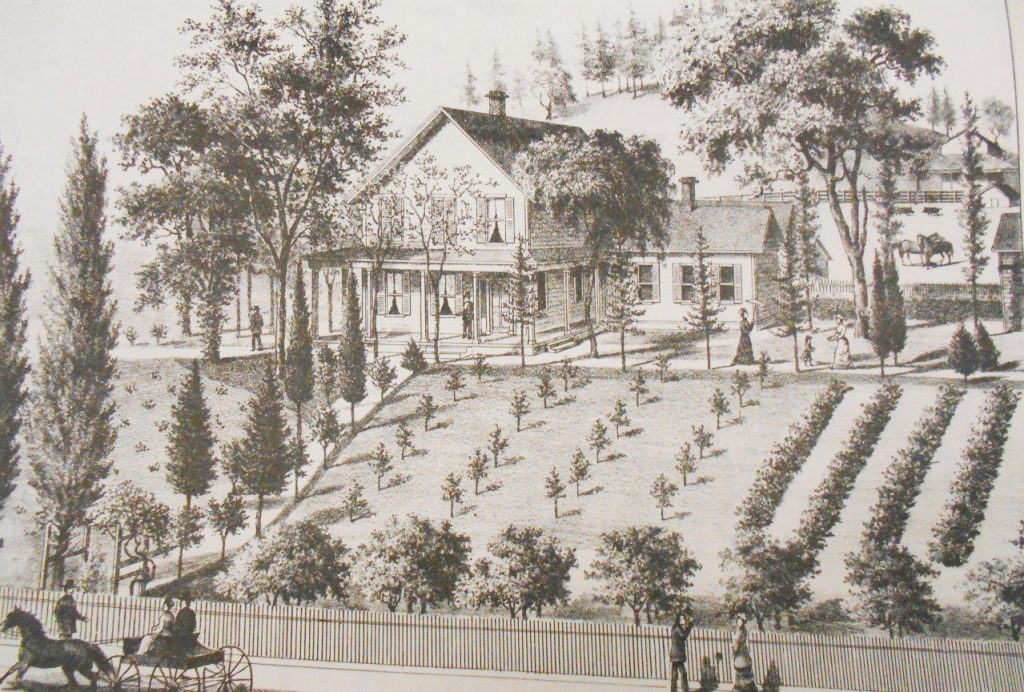

John Craig Boggs was 53 when he was elected Sheriff in 1879. He eventually retired to a ranch in Newcastle, a few miles west of Auburn, where he was involved with the fruit growers association. Boggs passed away in 1909 at 83 years old. He was preceded in death in 1891 by his 32-year-old daughter, Isabel. His wife, Louisa, died in 1898 at 68 years old. His son, John G. Boggs, also died in 1909 at 48 years old. The senior Boggs remarried in 1899 to Alice, who passed away in 1912. They are all buried in the Newcastle Cemetery in Placer County.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.