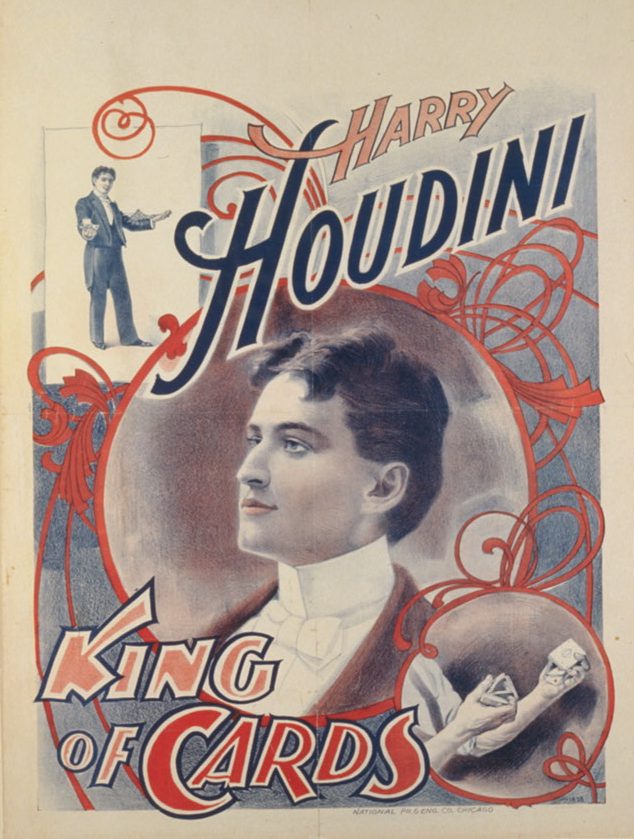

An anonymous letter from someone incarcerated at San Quentin led to performances from a band and world-famous escape artist Harry Houdini.

In 1915, eyes of the world were on San Francisco for the months-long Panama-Pacific International Exposition, a world’s fair celebrating the completion of the Panama Canal. It was also a chance for the city to showcase its recovery following the devastating 1906 earthquake. The fair ran from Feb. 20 until Dec. 4, 1915.

A band, a magician and a singer

In Hearst’s magazine dated February 1919, a reporter and columnist going by KCB recalled how the world’s most famous escape artist, along with a 90-piece brass band and a female singer, ended up in San Quentin.

“It was in San Francisco in 1915 during the progress of the Panama-Pacific Exposition. Over across the bay from San Francisco lies the San Quentin penitentiary. I was writing a column on the San Francisco Examiner (when a prisoner) reached me (via letter) early in November 1915,” KCB wrote.

The letter

“Dear KCB: I certainly do envy you and all the other good folk who are free to enjoy the beauties of the Exposition. Mostly I envy you the music of the bands. Before they sent me over here I spent a few days at the Exposition and my afternoons there, under the spell of the Philippine Constabulary Band, live in my memory as among the brightest spots along my way. I think I would be willing to have a few months added to my time over here if I were permitted to spend another afternoon or two at the Exposition.”

The response

“If Mahomet can’t come to the mountain, I said to myself, why not move the mountain to Mahomet? Thirty minutes later I stood in the presence of one William W. Barclay, Commissioner from the Philippines to the Panama-Pacific Exposition. I explained to him (someone in) San Quentin was very anxious to hear the Philippine Band, but who, for obvious reasons, wouldn’t be able to get over to San Francisco before the Exposition closed. ‘And it occurred to me,’ I said, ‘that maybe I might be able to borrow the band and take it over to him.’ For a moment or two Mr. Barclay just looked at me. (He agreed and said) there would be no terms.”

Steamer to San Quentin

The reporter arranged for a steamer to transport the band on Sunday then suddenly realized nothing had been coordinated with the prison’s staff.

“(A friend sent) word to the warden that we were coming and suggested (asking) Houdini (as well). We wired Houdini and in two hours had his promise to go. Then Miss Pauline Turner, who sometimes sang with the Philippine Band, (asked) to be taken along. On the following Sunday morning at ten o’clock, we boarded the ship and at noon were at the prison wharf being met by the penitentiary officials, their wives and children, and numerous trustees.”

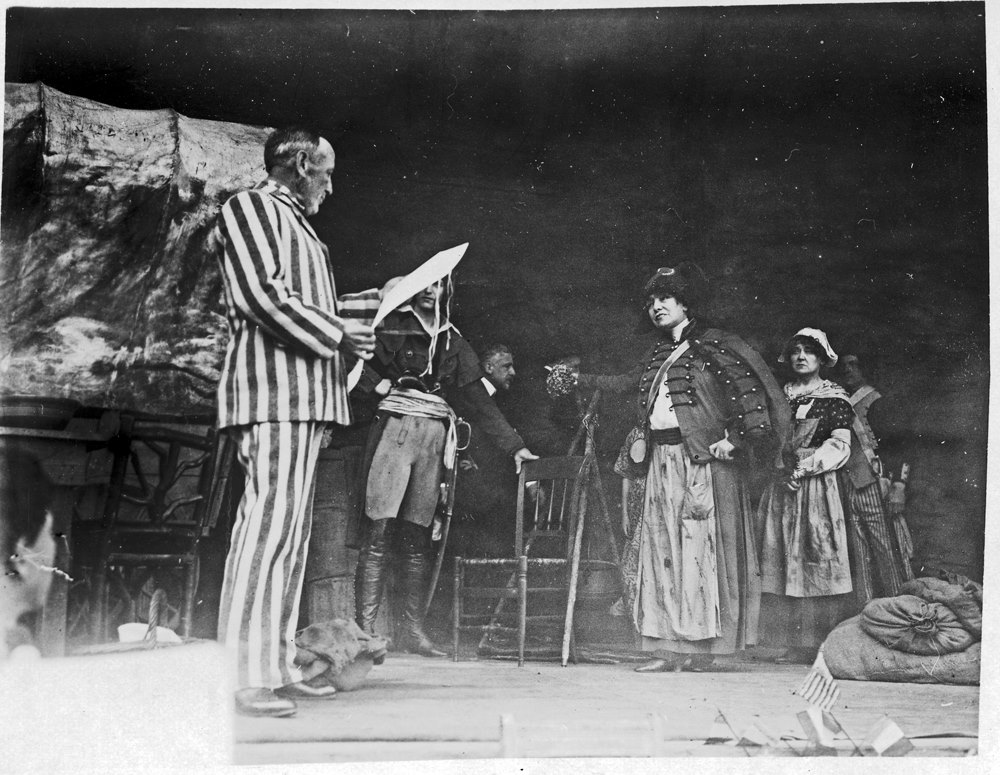

The band and singer perform

“One thousand men in prison garb were in the yard. And in one corner they had built a stand for the band and benches for the men to sit on. The Philippine Band outdid itself that day (because) it was giving without price. (The band’s) only pay was the light that came up from the faces of the men below and the cheers that arose at the close of each number. And Miss Turner sang so that her beautiful soprano voice must have gone out to the bay where, (heard by) the seagulls.

Houdini takes the stage

“And Houdini gave them everything he had and told them he was sorry the warden wouldn’t let him show them how he broke out of prison cells and freed himself from handcuffs. Altogether it was a wonderful afternoon. I suppose the man who wrote to me was in the crowd, but he gave no sign of his presence.

“I remember a lot of the men shook hands with me. Anyway, at 4:30 o’clock on that same Sunday afternoon, we tied up again at the Exposition wharf,” KCB wrote.

Mutual admiration

World-famous stage actress Sarah Bernhardt and Houdini both performed at San Quentin, a few years apart, but they didn’t meet until years later.

Their encounter is documented in the 1928 book, “Houdini: His Life Story” by Harold Kellock. The book was written from the recollections and documents of Houdini’s niece, Beatrice.

In 1916, Houdini, a fan of the actress, heard of an embarrassing situation in which the actress found herself.

While touring the United States, Bernhardt was presented with a bronze statue from notable American actors. She was given a plaque with the names of the “donors” and speeches were made at the ceremony at the Metropolitan.

In a few months, the actress received a bill for $350 for the statue. No one had paid for it and all those associated with the presentation and commission of the statue denied responsibility for paying the bill. She disputed the bill and returned the statue.

Word of the incident made it into the papers. Houdini was embarrassed on behalf of his fellow entertainers even though he wasn’t part of the project.

He immediately sent a check for $350 to the company and sent a telegram to the actress informing her of his actions. She thanked him for his generosity.

The following year, while both were in Boston, they finally had a chance to meet.

Bernhardt meets Houdini

“Early in 1917, during her last tour of the United States, after she had lost her leg, Bernhardt was playing in Boston at a time when Houdini was also filling an engagement there. She invited him to visit her at her hotel, and there for half an hour Houdini performed for her some of his choicest mysteries. The next day he was doing one of his outdoor stunts, and he invited the (Bernhardt) to watch the performance from a car as his guest,” according to the book.

When others touted his skills as supernatural, he quickly dispelled their beliefs.

“I do claim to free myself from the restraint of fetters and confinement, but positively state that I accomplish my purpose purely by physical, not psychic means. My methods are perfectly natural, resting on natural laws of physics. I do not dematerialize or materialize anything,” according to the book. Deeds of goodwill

Houdini had a soft spot for the less fortunate

“He was continually embarrassing managers by insisting that the entire registry of (nearby) old people’s homes be invited to a performance. Often suggesting (the theater provide) free transportation for them. In his later years he added prisons and (special-needs) institutions to his places of call,” according to the book.

For children, he often performed at orphanages and hospitals.

“Houdini’s love for children was (well-known) among managers. Hardly a week went by that he did not give a performance at some hospital or orphan asylum or other institution. He (also) invited (them) in great blocks to his regular shows. He even invented a whole performance for blind children,” according to the book.

“Playing in Edinburgh, Scotland, in cold weather, Houdini was shocked at the number of boys and girls on the streets without shoes. He bought three hundred pairs at a boot-maker’s (store) and invited all shoeless children to the theater. His fellow performers became infected with his (generosity and pitched in to help).”

The Houdinis never had children but looked forward to the day they could adopt after their careers wound down.

“Almost every week he would return from an exhibition at some asylum to tell (his wife) of some child he had almost brought home to her, but always they would defer such an adventure until the day they ‘settled down.’ On that elusive date, they promised themselves they would adopt dozens,” according to the book.

Houdini shuts down con artists

Houdini also took issue with psychics and mediums, claiming they took advantage of grieving families wanting to communicate with their deceased loved ones.

At first he confronted them, then took the fight to expose their fraud to higher levels

He wrote books, testified before the US Senate and publicly called out mediums and psychics. At the time, many con artists were serving time in California prisons. For Houdini, it was personal.

“While he devoted his life largely to devising methods for breaking physical bonds, he was also interested in breaking psychic bonds and communicating with friends who had passed (away). After the death of his mother, this curiosity developed into a passion,” the 1928 book states.

“His experiences with mediums led him to a warfare on frauds who strove to palm off phenomena of trickery and sleight of hand as manifestations from the dead. During the last few years of his life, all his energy and skill and showmanship were enlisted in this crusade.”

Houdini held out hope for communication after death

His debunking efforts were twofold. On one hand, he hoped the medium was real and could deliver a message from his deceased mother. Unfortunately, he was always disappointed and didn’t want others to fall into the con artists’ traps.

“Even after numerous disappointments, whenever we visited a new medium, Houdini, with closed eyes, would join in the opening hymn. Then (he would) sit with a rapt, hungry look on his face (making) my heart ache,” his wife recalled.

“I knew what message he wanted. Sometimes I felt myself tempted to give the medium the word that he longed for. I would be tempted—but I could not betray his trust in me. So the séance would go on. (He would see) the same trivial nonsense (and) usual tricks Houdini could do with his hands tied. The rapt look would fade from Houdini’s face. At his next visit to his mother’s grave, I would hear him say, ‘Well, Mamma, I have not heard.’”

When testifying before the U.S. Senate in 1926, he said, “I believe in the subconscious mind, in the hereafter, in the Almighty God. But, I do not believe the disembodied spirit can come back and do the things mediums claim they can do. I have no malice against any mediums. They say I am quarreling with their religion but that is their smoke screen. The money they charge means nothing. It is only the opening wedge to get fortunes (from) some old man or lady.”

The First World War

When the US entered World War I, Houdini cut his performance schedule so he could help with the war effort. Much like comedian Bob Hope decades later, Houdini performed for the troops and raised money events to sell war bonds.

“(Houdini gave) free performances for the soldiers at training camps and canteens and at benefit performances for war purposes,” the book states. “For two years he virtually devoted himself to this work, accepting all calls and traveling about, usually at his own expense.

“His lively imagination gave him an unflagging sympathy for the young men who were embarking to live in holes in the mud at a constant risk of being blown to bits or suffocated by poison gas. Whenever he performed before men about to embark for Europe, he would snap a succession of $5 gold pieces out of the ether and present one to each of the soldiers.

“None of the beneficiaries got more of a thrill out of this generous (gesture) than the performer himself. In this entertaining fashion, he gave away more than $7,000 of his own money to the soldiers. Incidentally he sold a $1 million worth of Liberty Bonds.”

Houdini dies on Halloween

In October 1926, at 52 years old, Houdini fell ill. Many speculated it was from a surprise blow to the abdomen delivered by a college student during a performance.

Despite pleas from his friends, Houdini continued touring and didn’t seek medical treatment. He died on Oct. 31 from what medical officials said was a ruptured appendix.

“Harry Houdini was a picturesque figure,” fellow magician Charles Carter wrote for The Billboard at the time. “He was much maligned and misunderstood. His life was unselfish and devoted to the betterment of those less fortunate. His deeds of charity were manifold (and) only his closest friends were (aware) of them. He fought (for) the respectability of magic on the stage, in the press, in the home, on the floor of the U.S. Senate (and) in the church. He was an institution, and we, the exponents of modern magic, owe his memory a debt that we can never pay. His name alone lent dignity to magic.”

Houdini’s name lives on today in TV shows, movies, books and is still synonymous with “escape artist.”

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Office of Public and Employee Communications

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.