By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Office of Public and Employee Communications

Famous artists, musicians and actors bringing their craft into state prisons can be traced back to the early 1900s. Today one might see actor Tim Robbins, singer M.C. Hammer or popular bands performing in one of California’s state prisons. Back in 1911 H.B. Warner received special permission to perform a play about a parolee, marking a major step in rehabilitation. When a female performer decided to do the same two years later, her efforts made headlines, encouraging others to follow in their footsteps, including Houdini.

Sarah Bernhardt steps into San Quentin history

On Feb. 22, 1913, a world-famous stage actress built on the rehabilitative efforts of others to bring art into San Quentin State Prison.

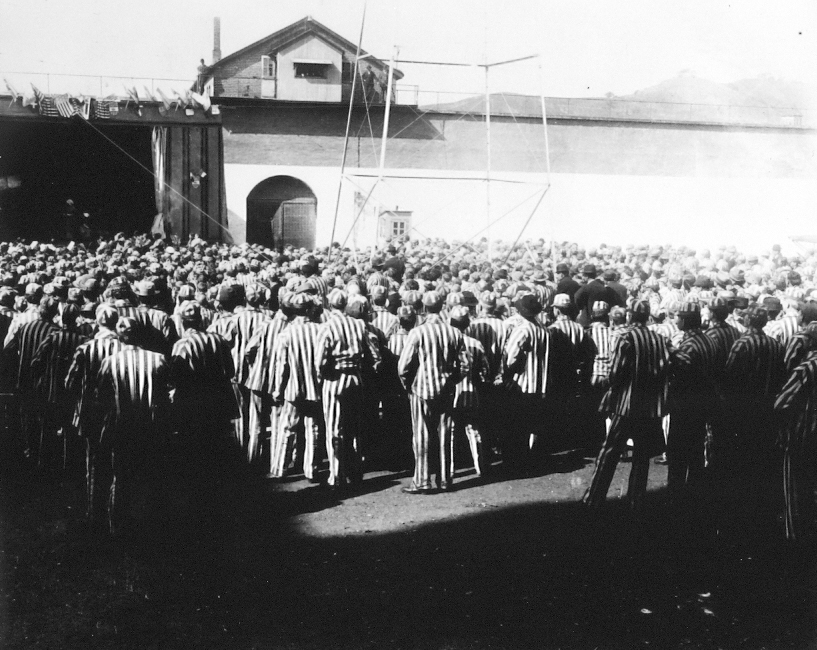

“The Californian authorities invited (Sarah) Bernhardt, then on tour of that state, to play before the prisoners of San Quentin,” reported the Literary Digest, 1913. “This must have furnished a new sensation for even Sarah, who has not led an absolutely quiet life. In her audience … were 2,000 prisoners of all races and nationalities. … Women were not excluded (and) a dozen condemned to death (were placed) in the front row.”

Bernhardt was one of the most famous actresses of the late 19th century. She and her acting company presented a performance of “A Christmas Night During the Terror,” penned by her son, Maurice.

“When the curtain rose displaying Sarah (as the character Marion), the French contingent among the audience shouted ‘vive la France,’” according to the report. “A (man) who murdered his wife and her lover ‘began to weep hot tears, then burst into hoarse laughter, which again melted to tears.’ Each scene ended with frenetic bravos and shrill whistles.”

Incarcerated audience expresses thanks

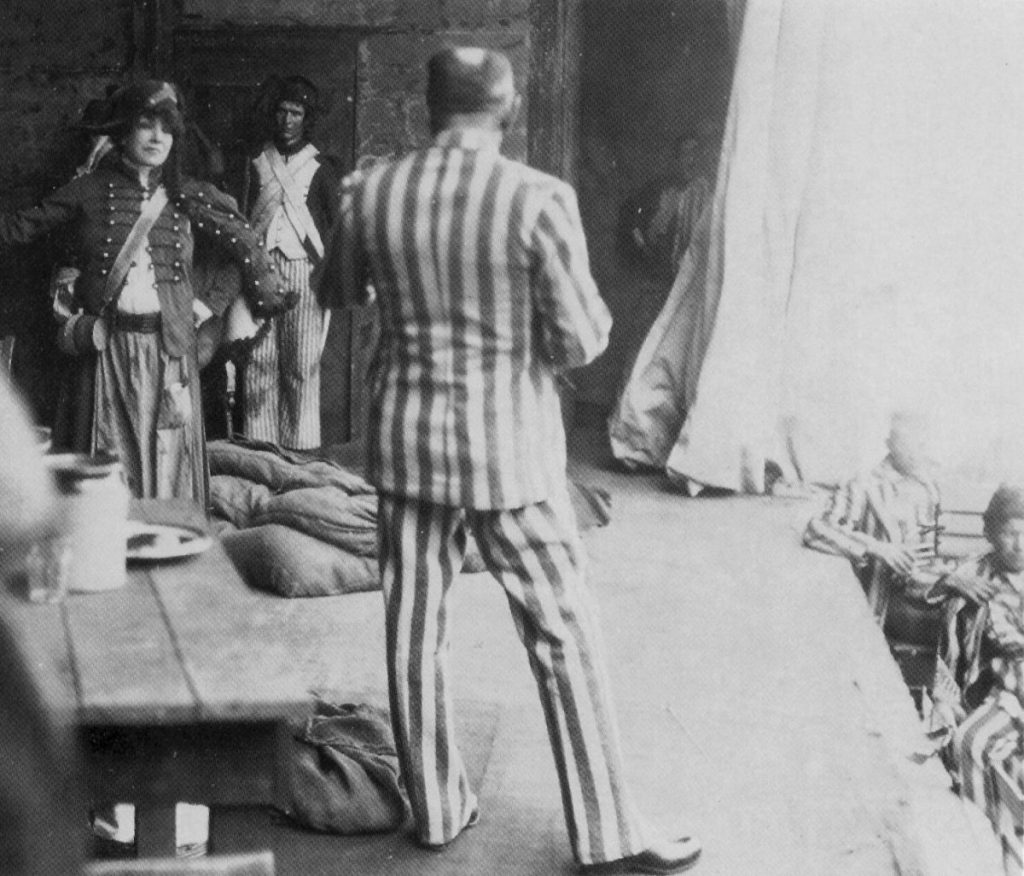

Abe Ruef reads a letter of thanks to actress Sarah Bernhardt, 1913, San Quentin. (San Quentin Museum Association.)

Sarah Bernhardt smiles while speaking with Abe Ruef, who represented the incarcerated audience.

Inmates gather to watch actress Sarah Bernhardt perform at San Quentin, 1913.

At the closing of the show, an inmate came upon stage and presented her with flowers picked on prison grounds and sang a song to her titled “Down from the Hilltops.”

Abe Ruef, a well-known inmate at the time, wrote an address to the actress, which was read on stage.

“Today, for one short hour, these walls of stone have vanished and – thanks to your marvelous personality and your enchanting art – we have been at perfect liberty in soul and mind, and captives only to the singular genius and incomparable art through which you have justly gained the title of ‘The Divine Sarah.’ For one short hour we have been free and untrammeled in our communion with the spirit of human greatness,” he wrote. “We present to you our thanks for the glories and splendors of the art which have graciously enabled us this day to enjoy.”

The actress also starred in a few silent films and has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. She died in 1923 and was buried in France.

War, flu suspend performances

Art in prison was eventually put on hold as serious events began to consume other countries and threatened to pull the U.S. into the fray. On June 28, 1914, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, lighting the powder keg that would become World War I. Soon the prison’s inmates would be put to work helping the national war effort through construction of a state highway system to ensure better transportation of troops and materials.

War wasn’t the only deterrent to art as rehabilitative programming. In 1918, public gatherings were discouraged as influenza, spread by servicemen returning from the front, swept across the globe. More people died from the flu pandemic of 1918-1919 than all those killed in the first World War.