From Broadway actresses to silent screen stars, early performers raised awareness about efforts to turn incarcerated people into productive citizens.

Actress pleads for young man’s parole

Stage star Olga Nethersole sought clemency for Percy Pembroke in 1910. She was also in a handful of silent films as well as Broadway performances.

Pembroke, originally tried for murder, was finally convicted of robbing Edward Stanley. He was sentenced to 10 years at San Quentin.

“Nethersole mailed Governor Gillett a petition for clemency,” reported the Sacramento Union, Jan. 10, 1910. “The letter follows a personal call (she) made upon the Governor.”

Her argument focused on Pembroke being 15 at the time of the robbery.

“Therefore, his trial and punishment should have been a matter for the juvenile court,” she said.

A few months later, Pembroke was granted parole.

Nethersole also had a taste of incarceration after a 1900 performance of the Broadway play “Sapho.”

While the play earned critical acclaim, controversy swirled around it, engulfing those involved. She was arrested, along with the male lead, for “violating public decency.” The play became a silent film in 1913.

Pickford, Fairbanks at San Quentin

Mary Pickford, known as “America’s Sweetheart,” was often cast in roles far younger than her years. The silent screen star founded her own film company, created United Artists and volunteered to help civilian efforts during both world wars. Somehow, the highest-paid actress in the country also found time to entertain residents at San Quentin.

“San Quentin: Inside the Walls,” published in 1991, features a photo of the smiling Pickford alongside San Quentin Warden James Johnston and Douglas Fairbanks. No date is provided for the photo but Johnston served as warden from 1913 until 1924.

Why were they at the prison? Pickford and Fairbanks, along with Charlie Chaplin, actively sold Liberty Bonds during World War I.

Johnston helped the war effort as well, so they probably visited the prison for a Liberty Bond rally.

“A rousing Liberty Bond meeting was held in San Quentin. Johnston and a (guest) speaker, addressed the audience of 400. Hundreds of dollars were subscribed before the meeting closed,” reported the Marin Journal, April 18, 1918.

The following year, San Quentin helped again.

“Prisoners at San Quentin have purchased $2,050 worth of Victory Liberty Loan bonds, putting the town of San Quentin over the top,” reported the Sacramento Union, April 26, 1919.

According to Johnston’s 1937 book “Prison Life is Different,” the duo toured the prison.

“(They) did not see quite as much of the prison as planned because (of) stormy weather,” the warden wrote. “But, ‘America’s Sweetheart’ brought a ray of cheer and brightness. (My wife) invited them to our home for lunch (and) our daughters, just home from high school, were all a-flutter.”

Prison visit helps earn Academy Award

Marion Benson Owens, the first woman to win an Academy Award for screenwriting, was one of the highest paid screenwriters in Hollywood. Born in 1888, the San Francisco native began working in Hollywood under the pen name Frances Marion.

Before talking pictures, she and screen star Mary Pickford formed a close friendship and Marion became her exclusive screen writer.

In 1930, she received her first Academy Award for writing for “The Big House.” ,

To make her story about prison life realistic, she visited San Quentin. She won her second Academy Award for “The Champ” the following year. In 1937, she penned the book “How to Write and Sell Film Stories.” She died in 1973.

Incarcerated actor brings craft to prison

Robert Griffin, alias Leroy Waltham, was a stage actor who served a year in San Quentin for bigamy.

Griffin was a veteran of the 1898 Spanish-American War’s Philippine campaign. During the war, he was “badly wounded,” landing on the government’s pension rolls, according to the San Francisco Call, Sept. 13, 1908. He was 31 years old at the time of his arrest, his eyesight fading due to his injuries.

For New Year’s Eve 1908, incarcerated actors performed a Griffin-penned short play, “The Sea Breeze.”

Meanwhile, former acting partner Mabel Violet Webber worked to secure his release.

“Griffin’s sight is gradually forsaking him and in a short time, will be totally blind,” newspapers reported. “Webber played in historical productions with Griffin on southern stages. She considered him a great actor. During his trial in Oakland for bigamy, she made a strong effort to prevent his incarceration. Having failed in that she has constantly endeavored to secure his pardon.”

Webber’s efforts were not in vain. The board recommended Griffin’s sentence be commuted.

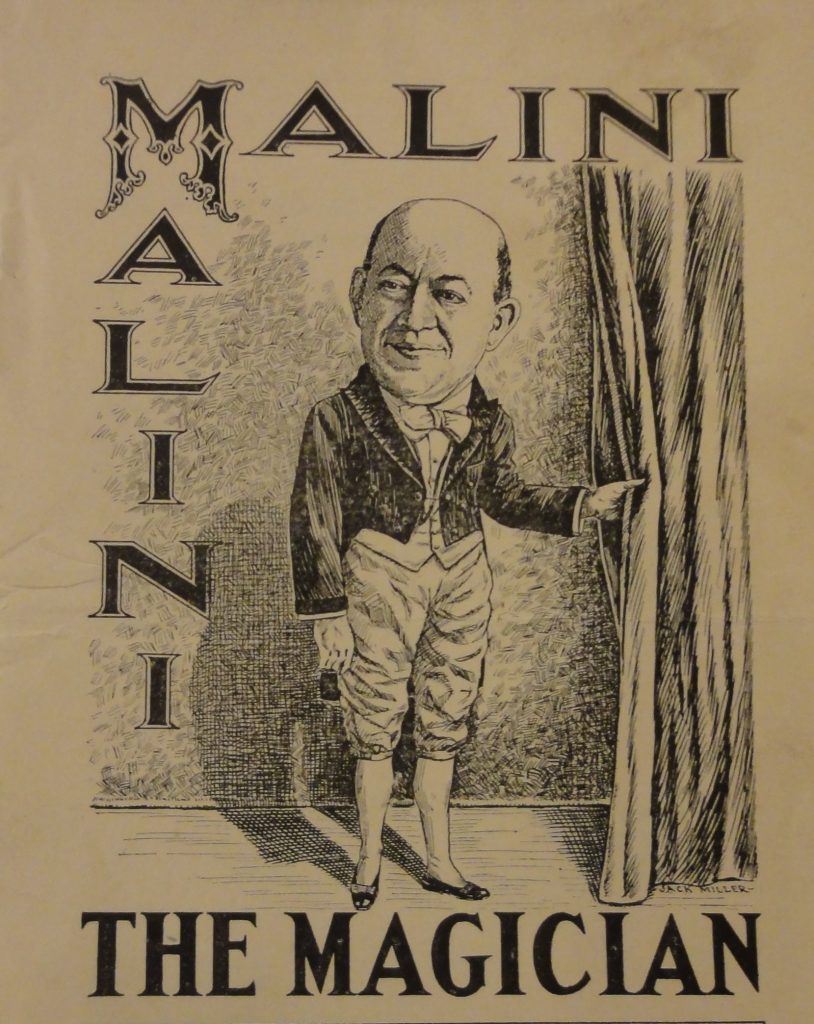

Malini amazes with magic

Four years after magician Harry Houdini wowed inmates with his performance at San Quentin, another magician took to the stage behind the walls of the famous institution.

“Professor Malini gave the inmates of San Quentin an exhibition of magic art (on Sunday, Dec. 14),” reported the Marin Journal, Dec. 18, 1919.

“Grouped in the prison theater were 1,700 men garbed in convict gray,” reported the San Francisco Examiner, Dec. 15, 1919. “He fairly startled some of his audience. (Many) had been behind the bars for so many ears that Malini was like a mystic to them.

“He ran the full gamut of tricks and the men in gray laughed and cheered. The show was made possible by the effort of Chief of Police D.A. White, through the cooperation of Warden James A. Johnston and the prison officials. It was under the immediate direction of Captain Randolph.”

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.