Leo Stanley served as a doctor for San Quentin State Prison through much of the first half of the 20th century, modernizing the medical department.

The year was 1913. Woodrow Wilson became the 28th President of the United States and the Ford Motor Company instituted the world’s first moving assembly line to crank out the Model T. Meanwhile, 27-year-old Stanley was appointed resident doctor at San Quentin.

He served as the San Quentin doctor until 1951, only leaving for a brief time to serve in World War II. When he retired, Harry Truman was in the White House, the Korean War was raging and America was tuning in to watch the first episode of “I Love Lucy.”

Coming into a prison seemingly stuck in the 19th century with outdated medical methods and equipment, the young doctor quickly pushed the prison into the modern era.

Love, life and a career

Choosing to study medicine, Stanley followed in his father’s footsteps. He earned his medical degree from Cooper College in 1912. The same year, he also tied the knot.

“I fell in love with Romaine, (and needed to get a job),” he recalled in 1974. “We were married a month before I graduated medical school. Being an intern, (I earned) no money at all, only my board. When this offer for a position came along (at) San Quentin at $75 a month to be an assistant, we jumped at that.”

He didn’t plan to stay long, maybe a few years, and then open a private practice.

“I felt (San Quentin) would be a good place to get some experience (but wanted) to become a country practitioner, not a city specialist,” he said.

At first, his goal was simply to get established in the medical field.

Tuberculosis has personal connection

In his book, “My Most Unforgettable Convicts,” Stanley recounts early efforts to stop the spread of tuberculosis. Thanks to Stanley and his newly implemented medical screening procedures, 60 tuberculosis patients were identified in his first year.

“With the help of Warden James A. Johnston and a sympathetic Board of Prison Directors, we built an open-air hospital of 4,800 square feet. (It was) without bars and with sun areas open to the sky, on the flat roofs of three of the original buildings surrounding the plaza. Here we moved both the active and (early-stage) patients. The accepted treatment for tuberculosis in those days (was) no work and the best food.”

His drive to learn as much as he could about tuberculosis was personal.

“My interest in this dreaded disease was more than humanitarian. (My wife) developed tuberculosis shortly after we went to San Quentin (and) was bedridden in our home on the hill above the prison,” he wrote.

The sudden turn in her health meant Stanley needed to offer stability.

“At San Quentin, she had the best of care. We had our own home (and a convicted) murderer assigned to our place. He became (her) nurse and prepared our food,” he said. “He took great care of her and lived with us until 1926. She improved enough that we felt we could move to San Rafael. She and the (helper) made a model of the house she wished to have built.”

Trustee for San Quentin doctor

The trustee helper was Lim Foon, someone the doctor took under his wing and eventually helped him petition for a pardon.

“When he was only 18, he had been sent up from Stockton for murder. In a (gang) war, a Chinese man had been killed on the street in front of a poultry store (where Lim was visiting a friend). Frightened, he fled by the back door and hid in a large chicken coop. Police found the sweating, shaking boy and interpreted his fear as a sign of guilt. He was convicted in a court where he was badly represented and sent to us,” Stanley wrote in his book, “My Most Unforgettable Convicts.”

An elderly man on his deathbed later confessed to the murder.

“After much investigation and at considerable expense, I was able to get a full pardon for him from Governor Friend Richardson,” he wrote. “Years before his pardon, prison staff were allowed to have a cook or (assistant) from among the prisoners and Lim Foon was assigned to us. He soon developed a special fondness for Mrs. Stanley, who taught him to read and write from her sickbed.”

Cruise ships become an option

After his wife died, Stanley remained a bachelor for a dozen years. Lim Foon stayed with the doctor, continuing to help. When Stanley remarried, his helper took a different job.

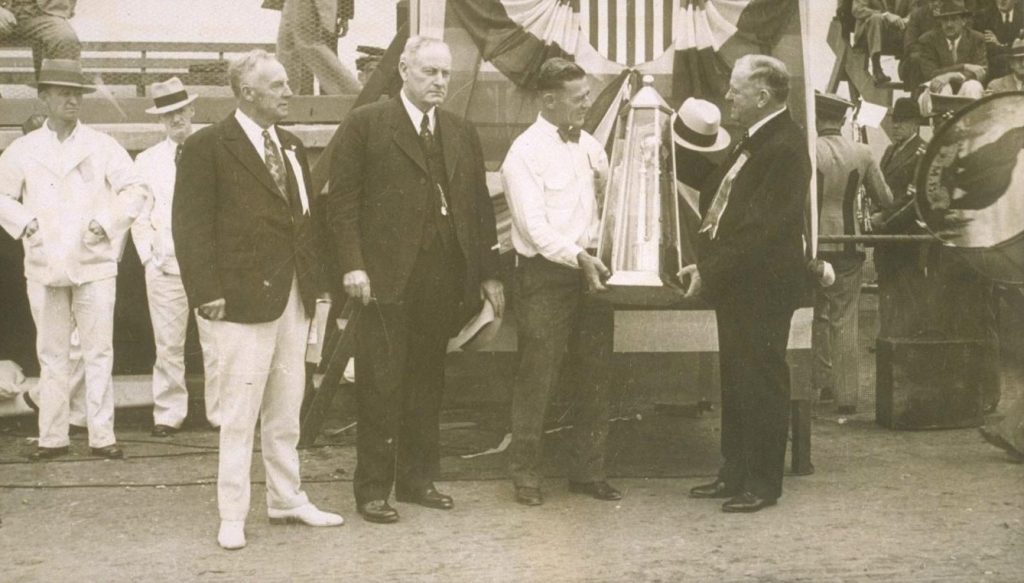

To take a break from the day-to-day operations of the prison’s medical department, in 1929 Stanley took a temporary job as ship’s surgeon on the SS Malolo.

The 1929 excursion was revolutionary for its time. The ship’s owners worked with the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce to organize the first “Around the Pacific” cruise, visiting 14 countries.

“On (Sept. 21), 356 millionaires set sail from San Francisco on an ambitious 90-day, 24,000-mile odyssey aboard the fastest and most luxurious ship in the Pacific,” according to the Pioneers of Santa Clara County. “Thirty-eight days into the tour, somewhere between the American-Governed Philippines and French Colonial Saigon, passengers received news about stock markets crashing all around the globe.”

Improving San Quentin’s conditions

When he was appointed resident physician in 1913, the young doctor immediately sought improvements at the prison.

First, he sought to improve the chances of people post-release by improving their overall health while incarcerated.

“(We intend to have) men in a physical condition superior to that with which they entered. The medical department has made favorable and encouraging progress,” Stanley wrote in a 1914 prison report. “The hospital has become a modern and up-to-date institution where the latest methods of treatment are in use.”

He often performed plastic surgery on inmates as a way to improve their self-image and help their post-release reintegration into society.

“Considerable plastic surgery has been done, particularly for deformed noses (and) and ears,” Stanley wrote in a 1918 report to the warden.

The men’s appearances were so transformed, police weren’t sure they’d be recognizable from their earlier photographs.

“When Stanley began remodeling the wrecked features of sundry gentry to whom fate, (and violence) had been unkind, he (didn’t think) of making trouble for the cops. So he restored many a nose which was off its bearings,” reported the Riverside Daily Press, Dec. 12, 1917.

Because of this, the warden ordered all prisoner be re-photographed when their sentences were complete.

Experiments tarnish San Quentin doctor’s legacy

What garnered interest from the public as well as the medical community were his efforts to restore youth and vitality.

“Youth is returning to the man who received the ‘life-giving’ gland from Tom Belton, the Merced murderer hanged last Friday. The prison physicians stated that he had a better appetite and increased pulse,” reported the United Press Dispatch, Oct. 21, 1919.

Other medical professionals were also pursuing similar treatment for older patients, often using animal glands.

“Dr. Serge Voronoff (of France) urged municipal cold storage plants be built to (preserve) life-giving interstitial glands taken from hopelessly injured men. He said even the dead can donate because organs do not die immediately when the heart stops,” the report stated. “The transplanting of glands, he says, gives renewal of human youth and strength.

“Stanley has become an international figure in the surgical world. (He has had) success in rejuvenating old and senile prisoners by transplanting the (testicles) of (executed) prisoners.”

Decades later, this research was debunked and the experimental practices forever tarnished the doctor’s reputation.

“During his tenure at San Quentin, Stanley performed medical experiments on prisoners involving testicular transplants, attracting national media attention. This notoriety would cling to him until his death in 1976,” according to California State Archives.

San Quentin doctor saves warden’s life

He briefly served as San Quentin’s warden in 1933 while Warden Holohan recovered from illness.

“The regular warden, Holohan, was sick, so I was chosen to administer the prison. I did not want to do anything (the warden) would think (undermined) him and his policies,” Stanley wrote. “I made numerous tours of the prison, which Holohan, because of his ill health, had been unable to attend to. Clean-up (crews) were organized. These, under the supervision of a reliable ‘con boss,’ did wonders in policing the grounds. And the men in these work (crews) were kept busy and out of trouble.”

Stanley returned to his regular role when the warden was well enough to return to duty.

Warden fights for life after attack

A few years later, Stanley worked feverishly to save the warden’s life after he was gravely injured.

“Doctors today gave James B. Holohan, warden of San Quentin, a better than even chance to recover from serious injuries received in yesterday’s prison break. He was not yet out of danger. (Holohan) had a frontal fracture of the skull and 19 lacerations on his scalp. He (had been) struck from behind by a revolver in the hands of Rudolph Straight, the convict later killed in the escape plot,” reported the Madera Tribune, Jan. 17, 1935.

“When he regained consciousness, Holohan told of the vicious attack which had felled him and split open his skull. ‘I was struck from behind,’ he said. ‘I turned quickly to put up resistance when the blond man, the leader of the gang, swung a gun over his head and hit me with the barrel. (So,) I dropped to the floor, losing consciousness apparently for I don’t know what happened after that. It all came in a flash.’ Stanley used all his skill to pull the warden through a critical period immediately after the beating.”

Through this tumultuous time of the 1930s, Stanley fell in love again.

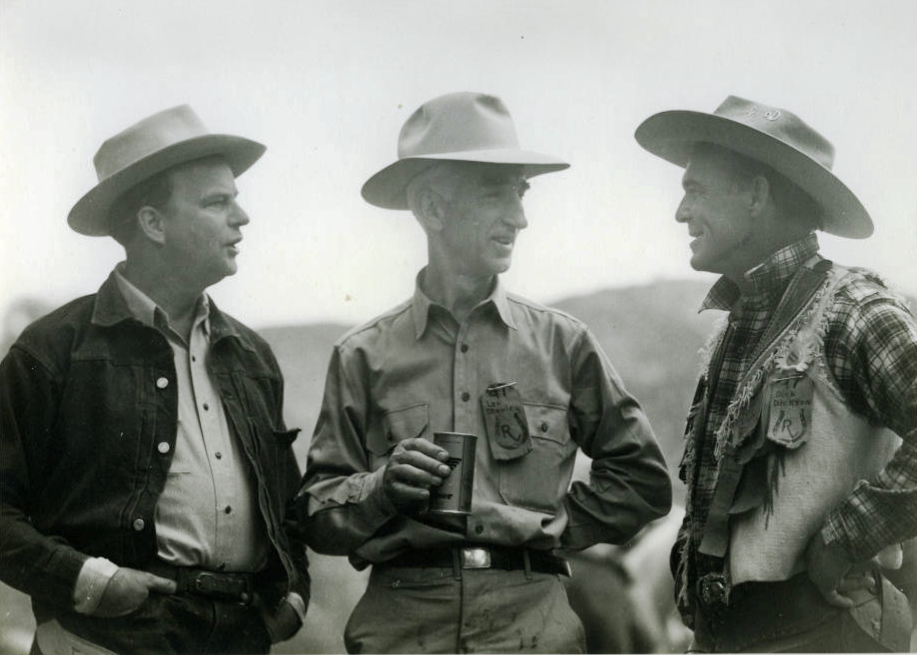

“Being a bachelor for a long, long time I (would) travel around the country a good deal with Warden Holohan inspecting prison camps and so forth,” he recalled in 1974.

Stopping at a pear orchard, he met Bernice. They married in 1938.

After only a few years of marriage, the country was plunged into World War II.

San Quentin doctor goes to war

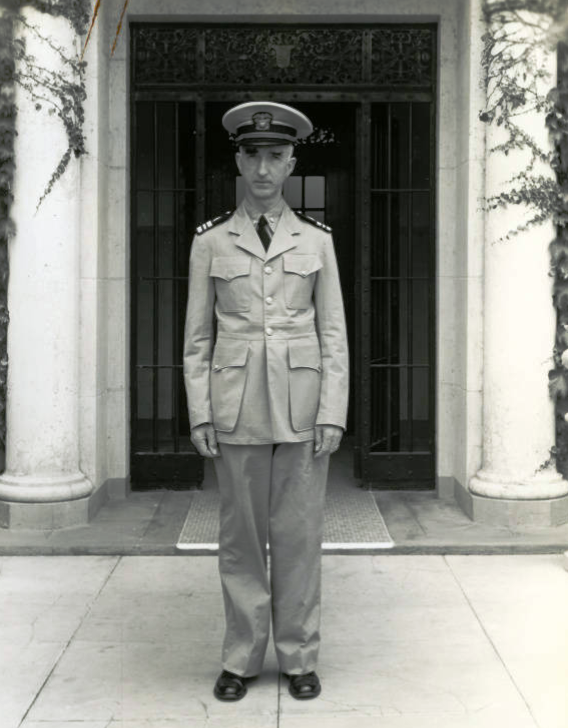

Less than two weeks after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Stanley was called into service as a lieutenant commander in the US Navy.

“As soon as war was declared, I was assigned to the Naval Hospital on Mare Island. I served there about three months, and was assigned to the office of Naval Officer Procurement in San Francisco. In that office it was necessary for me to interview many of the applicants for office,” he said.

“(In 1942,) my orders were changed and I was assigned to the Naval Hospital at Pearl Harbor. I remained there a year taking care of the casualties from the South Pacific. At the end of that year, I was assigned to the hospital ship Solace and remained on her for a year. She traveled all over the Pacific (participating) in the battles at Eniwetok, Saipan, Guam and other places.”

Hospital ships, positioned next to destroyers as they shelled beaches, tended to the wounded, staying just outside the active combat zones.

“In a battle, the battleships went in first and strafed the island. The transports went in and were unloading their troops with landing boats that went ashore. The Solace was right in behind them waiting to receive the wounded (coming) from shore. Outboard from that were some of the destroyers which were lobbing shells over into the island.

After taking part in other military assaults, he was ordered to report to the Naval Hospital at Treasure Island.

“I was there almost a year before the ware ended and was in charge of the so-called ‘sick officers’ quarters,” he said.

San Quentin doctor returns to prison post

After the war’s end, he took a year to acclimate himself to civilian life before returning to San Quentin.

“Two of San Quentin’s well-known officials are returning to their former posts, according to an announcement from Warden Clinton Duffy. Stanley, long-time chief surgeon at the penitentiary, plans to return to his old post with the title of chief medical officer about Oct. 1. Stanley took a leave of absence during the war, serving with the navy as a captain in the Medical Corps, and has since been taking a year’s absence for rest. Also returning to his post as assistant to Dr. Stanley will be Dr. Alex Miller, who also took a leave for duty in the armed forces. Dr. David Schmidt of Larkspur, who has been serving as acting chief medical officer during Stanley’s absence, will return to his former post as chief psychiatrist,” reported the Sausalito News, Sept. 4, 1947.

Post-war slice of paradise

He and his wife purchased some land after he returned from the war.

“Well, when I came back from the war in ’46, after being out for almost four years, (my wife experienced) a pretty hard time in San Rafael. (There had been) sugar rationing (and) gas rationing,” he said. She requested they leave the city and seek a quiet life in the country.

“In Fairfax and here on the top of the hill 800 feet above sea level she found what was then called ‘Crest Farm’ and still has that same name,” he recalled in 1974. “(Purchasing the property) took all of my funds which I had accumulated all of my life. We love it very much; it’s really a paradise. We have 10 acres (with) fruit trees, redwoods, gardens, about everything that one would want.”

The prison in the post-war era had drastically changed, as had the medical practices he established. He officially retired his post in 1951, his career touching five decades.

Life after retirement

The sea called again and he returned to being a ship’s surgeon aboard cruise lines.

“(After retirement,) I did a little private practice in San Rafael but the opportunity came for me to be relief surgeon on these trans-Pacific liners. (They were) going to (east Asia) two or three times a year. I met many wonderful people and the experiences on-board were very interesting.

“Because the ship surgeon, you might think it’s an easy job but it’s far from that because you have a passenger list of 400 to 500 and a crew of 300 or 400. You’re on your own out there and you have to do everything. I (have) delivered babies and taken care of coronaries, broken bones, cuts, everything that you would have to do in general hospital,” he said in 1974.

Stanley died in 1976 at 90 years old.

Learn more about Marin County at the Anne T. Kent California Room of the Marin County Free Library.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.