Ben Merritt had long law enforcement career

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Office of Public and Employee Communications

One of the early correctional officers at the state’s two prisons survived an attack by a notorious inmate, helped track down an escapee and sought to get a pardon for someone he believed was wrongly convicted.

His story, like many early correctional staff, has been lost over time but their experiences helped shape today’s CDCR. As part of an ongoing effort to honor the memories of these pioneering penologists, Inside CDCR took a closer look at Ben Merritt.

In 1895, Madera County Deputy Sheriff Merritt went to work at San Quentin as a correctional officer. He had already been a deputy for 14 years.

While at San Quentin, Merritt was one of the staff members attacked by inmate Jacob Oppenheimer. When unlocking his cell, Oppenheimer lunged at Merritt and began choking him. Merritt overpowered the inmate with “superior strength,” as the newspaper reported.

Inmate breaks trust, escapes over women’s ward wall

Merritt also helped capture an escaped inmate in 1898. Today, if an inmate escapes or walks away, CDCR’s Office of Correctional Safety is involved. Back then, no such office existed.

“(Alton Gould) escaped from San Quentin Sept. 18 by getting into the women’s ward and climbing over the east wall of the yard. He was recaptured on Sept. 23 by Constable Louis Hughes of San Rafael and Guard Ben Merritt, two miles north of Camp Taylor, after a running flight,” reported the San Francisco Call, March 4, 1899.

In his own words, Gould described the escape.

“On Wednesday, Sept. 14, 1898, I made up my mind to get away from San Quentin. The following Sunday evening the opportunity came and I took advantage of it. With my rope and muffled iron hook, I scaled the east wall of the prison and made my way along the road toward Schuetzen Park,” the newspaper reported. “Then I heard the alarm bell and took to the hills. Guards passed close to me that night repeatedly. I had on convict garb and had to get along without being seen. I subsisted on grapes and fruits which I stole from the orchards. Often I became bewildered and went in a circle, knowing nothing of the country. Monday night, with my stripes still covering me, I met a hunter, but he paid little attention to me. Tuesday I grew faint and exhausted, and made little headway. I slept in an orchard, and Thursday I broke into a cabin and stole a shotgun, shirt and pair of pants. Then you bet I discarded the old stripes. I got an old overcoat too. Thursday night I walked all night and was still walking when Guard Merritt surprised me.”

Prison staff, K9s track escapee for days

“Gould (escaped) at 7:30 o’clock in the evening. Guards and bloodhounds were on his trail half an hour later. Gould is a tall man with blue eyes and confiding manners. Prior to his escape he was made a trustee in Captain Edgar’s office, and soon had the confidence of all the officers. Just after the sun went down that autumn evening, this blue-eyed burglar smashed his way through the transom of the captain’s office, into the female wards, and disappeared over the walls by means of a hook and rope, found dangling in the breeze shortly after. He went right under a Gatling gun. The women had all seen the clever little ‘job’ and listened breathlessly for the rattle of the big artillery on the hills around the prison. But Gould was safe that night. Mounted men rode through the hills all night and for four succeeding days and nights, searching every foot of underbrush, every cabin and farmhouse, far and near. The manhunters were getting discouraged when Guard Benjamin Merritt saw his convict going along the road near Tocoloma, carrying an old gun and dressed in a shabby suit. ‘Halt!’ and a bullet from Merritt’s Winchester (rifle) only made Gould take to his heels. He ran across a high trestle, stopped and leveled his gun at Merritt, changed his mind suddenly and made for the brush with the guard in hot pursuit. Inside of five minutes the escaped convict was looking into the barrel of a rifle with his hands in the air,” reported the Evening Sentinel, May 12, 1899.

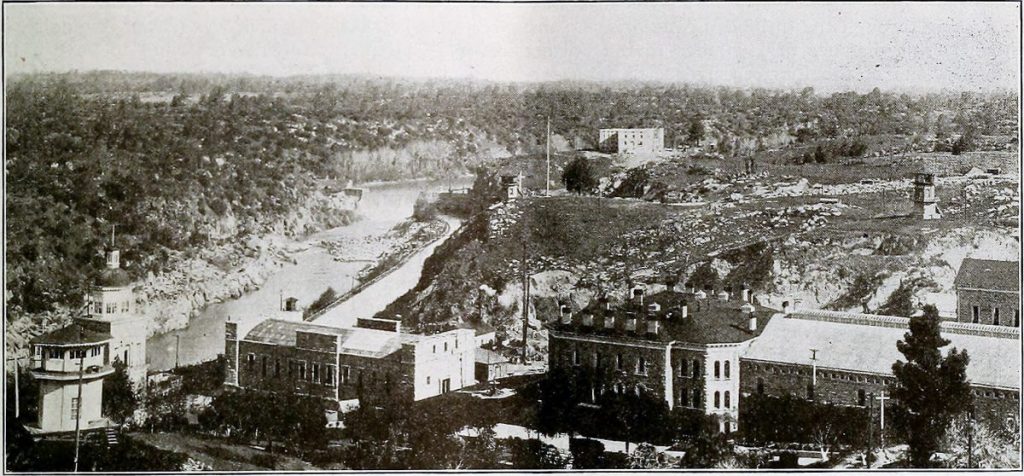

After a decade at San Quentin, Merritt was let go but was only out of a job for a few months. He was asked to come to work for the new warden at Folsom Prison.

“Ben Merritt, formerly of this city, and within two months ago, a guard at San Quentin, has accepted a position under Warden Yell of the Folsom Prison,” reported the Marin Journal, June 29, 1905.

By 1909, he had been promoted to captain. His other life changing event was saying “I do.”

“Captain Ben F. Merritt, a member of the warden’s staff at Folsom penitentiary, married Mrs. Spano of Fresno last Saturday,” reported the San Francisco Call, Dec. 21, 1909. “Captain Merritt has been identified with the sheriff’s office (and) the Folsom penitentiary for upward of 30 years, having taken an active part in the hunt for Evans and Sontag some years ago. Captain and Mrs. Merritt spent yesterday in San Francisco and will return to Folsom today.”

Capt. Merritt advocates for pardon

Captain Merritt even advocated for a pardon on behalf of a convicted murderer serving a life sentence at Folsom Prison. Merritt wasn’t the only one to believe in the man’s innocence as the first two juries couldn’t reach a decision.

Jose Verduzco was 20 when he was convicted of murder in the shooting death of a Millview man in 1909.

Unfortunately, Merritt died before he could fully push for Verduzco’s release. He was 63 when he passed on Nov. 11, 1915. He was born Feb. 1, 1851 and worked for the state’s two prisons for a full two decades.

“Benjamin F. Merritt, husband of Elizabeth Merritt, … a native of Maine. Funeral from his late residence of Represa … interment in citizens’ cemetery, Folsom,” reported the Sacramento Union, Nov. 13, 1915. Today, the cemetery in Folsom is known as Lakeside Memorial Lawn Cemetery. He was survived by his wife, four daughters and two step-daughters.

In 1919, the inmate was pardoned.

“Jose Verduzco was of a quiet disposition, never carried weapons, made no attempt to escape, and insisted that he was innocent before and during the trial and while in prison. While in (prison), he was a model prisoner,” reported the Madera Weekly Tribune, Feb. 27, 1919. “After watching the prisoner for a few months, (Merritt) was convinced of his innocence (but) died before use could be made of his belief.”