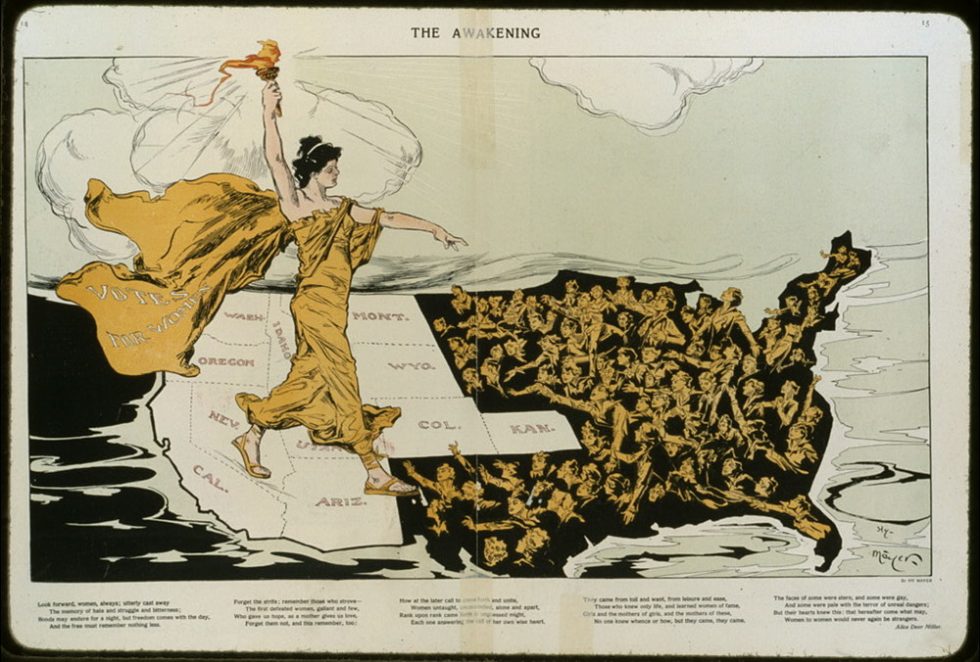

While the state created the prison matron position in 1885, job roles didn’t expand until the suffrage movement.

The first statewide push for Women’s Suffrage was in 1896, but the effort failed. In 1911, after more than a decade of campaigning and marches, women won the right to vote.

The suffrage movement saw changes in prison jobs, volunteerism, and oversight boards.

By the early 1970s, women were hired as correctional officers in men’s prisons. During the same decade, women began entering other prison jobs typically held by men.

Women fought long and hard to earn the right to work alongside men in the state prison system. Inside CDCR looks at part of their struggle.

Suffrage movement turns to prisons

Clara Shortridge Foltz, the first woman to be admitted to the California bar, was appointed by Governor Gillette to the State Board of Charities and Corrections, an oversight board tasked with keeping an eye on hospitals, jails, asylums and prisons.

“It was very good of the governor,” Foltz told the newspaper. “I feel highly honored, not because it is myself alone, but because the appointment has been given to a woman.

“Governor Gillett recently has been the subject of criticism throughout the state because of an alleged statement to the effect that he did not believe in women holding public office. I believe that I can accomplish much good on this board.”

The more specific Board of Prison Directors did not have a woman appointed for many years. They acted as direct oversight of the warden and as a sort of early Board of Parole Hearings.

Woman named secretary of board

Beginning in 1907, a woman made headlines when she was hired to be the secretary of the board.

“Woman for Secretary,” reads the headline, Sacramento Union, Sept. 21, 1907. “Word has been received at the capitol of the selection of Miss E. Herriott of Alameda as secretary of the state board of prison directors, to succeed P.H. McGrath of this city, who resigned. This is the first time that a woman has ever been elected to a position of this kind, and Miss Herriott’s appointment comes as a surprise, as there were others more prominently spoke of for the place.”

She retired three years later.

“Miss Elizabeth Herriott, for the last three years secretary of the state board of prison directors, has tendered her resignation to take effect Feb. 1. Miss Herriott will leave San Francisco Feb. 5 on the steamship Cleveland, when that vessel sails for a trip around the world,” reported the San Francisco Call, Jan. 22, 1910. “It is the intention of Miss Herriott to leave the (steamship) in Europe, where she will spend several years studying history and language.”

Pressure to appoint woman to board

In 1914, women attorneys rallied to pressure the governor to appoint a woman to serve on the Board of Prison Directors.

“Women attorneys, who requested Governor Johnson appoint a woman on the state board of prison directors, received the endorsement of several judges,” reported the Los Angeles Herald, Jan. 23, 1914.

Their attempts were unsuccessful.

In 1922, the fight for a woman on the prison board was still underway.

“Governor-elect Friend Richardson will be asked to appoint a woman as a member of the state board of prison directors. (The) board always has been composed exclusively of men. (They supervise) the cases of 4,000 male convicts as compared to 60 women,” reported the Chico Record, Nov. 23, 1922.

Women’s correctional roles expand

In 1933, California Institution for Women’s (CIW) opening sparked the notion of women taking on more correctional duties statewide.

“Mention was made of the possible appointment of a woman as a member of the State Board of Prison Directors. Specifically (they mentioned Rose B.) Wallace, (current) head of the Board of Trustees of (CIW),” according the Sausalito News, Sept. 39, 1933. “We have been aware of the good work (Wallace) has done in getting the Legislature to establish this reformatory for women. (She also has a) deep interest in this kind of work. It might not have been considered as a woman’s place some years back. Now we have women on juries who weigh evidence by which both men and women are sent to prison. A woman could certainly serve her state in assisting to administer its penal institutions.”

In 1941, state senators sponsored a penal reform bill, including the creation of a department to oversee the prison system. The bill called for a female to have a regular seat on the board.

“Designed to promote improved administration, a bill creating the State Department of Corrections has been adopted by the Senate,” reported the Sausalito News, May 15, 1941.

The department wasn’t created until 1944.

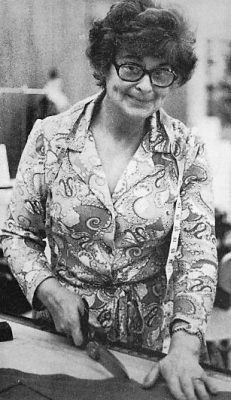

Female hired to run prison factory

Factories saw women workers during World War I and World War II, but they didn’t break into law enforcement until much later.

After the first women began working in male prisons in the 1970s, they also began to take on other jobs in traditionally male-dominated fields.

One such post was running a factory at San Quentin. In 1974, Pat Schecter was tapped to be the first woman to do just that.

“Santa Monica College student Pat Schecter will become the first woman in the United States to be a textile factory supervisor in the state correctional industries. She will be working directly with the inmates of San Quentin State Prison,” reported the Santa Monica College Corsair, Oct. 9, 1974.

“She will supervise the instruction and making of garments such as the orange vests worn by street construction workers. Prisoner-made products are not sold to the public. Other duties will include managing personnel and public relations.”

Schecter spotted a help-wanted ad and the notion of working in a prison piqued her interest. After applying, taking a series of tests, and an interview, she was offered the job.

Del Brown, manager of San Quentin State Prison Correctional Industries, made the job offer.

“Now 54 years old, (the British native) received her training in technical college,” the paper reported. “In 1964 (she moved to Los Angeles) to continue work in the fashion industry. Schecter is a bit modest about the whole thing but hopes it will pave the way for women”.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Office of Public and Employee Communications

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.

Related Content

Echoes from the Past: Restoring history’s missing pages

While researching stories for the Unlocking History series, we often find damaged documents, missing photos, or incomplete information. One example…