AC McAllister spent life serving public

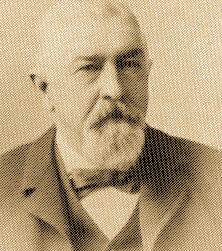

Captain of the Yard Archibald Charles McAllister earned the respect of the incarcerated at San Quentin then went on to serve the indigent and elderly in Marin County. McAllister spent most of his adult life devoted to public service.

From Assembly, to firefighter to San Quentin official

AC McAllister was born in England in 1831, left New York aboard a steamer for California in 1852. Six years later, he arrived in Marin County. In 1861, he was elected to the state Assembly but the election was contested and he lost the seat a few months later. He tried his hand at business and a newspaper story indicates he owned a saloon in the 1860s and early 1870s. In 1869, he served as a Justice of the Peace in San Rafael.

McAllister was instrumental in the founding of the township at San Rafael, including acting as treasurer for the newly founded Hook and Ladder Company.

“June 3d (1871), a Hook and Ladder Company was formed, with the following officers: C. W. J. Simpson, Foreman; O. D. Gilbert, First Assistant; J. O. B. Williams, Second Assistant; J. A. Barney, Secretary, and A. C. McAllister, Treasurer,” according to the History of Marin County, published in 1880.

McAllister was a charter member of the Marin Lodge, No. 200, of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, formed Feb. 24, 1872.

On Dec. 5, 1874, McAllister was officially a member of the of the newly named San Rafael Hose Company, No. 1.

He went to work at San Quentin in 1875. His first year proved to be a trial by fire. A devastating blaze ignited at the institution in 1876 but thanks to McAllister’s quick thinking, he was able to enlist the help of the inmates to contain it. He promised he’d recommend them for special consideration if they helped instead of using the confusion to escape. The inmates succeeded in saving many buildings and lives. In return, McAllister made good on his word.

The governor commuted the sentences of more than 100 inmates who participated in the fight to save the prison. The Brotherton Brothers saw two years knocked off their sentence, as did many of the others.

This is the same model used decades later when the California Institution for Women (CIW) suffered a disastrous earthquake in 1952. The female inmates were kept in tents until they could be transferred to a new prison. Based on their good behavior, the governor commuted a portion of their sentences.

From at least 1875 to 1880, McAllister was Captain of the Yard at San Quentin. He was also appointed as a trustee for the San Quentin school district.

McAllister “crusaded against opium and drove the (prison) price up to $60 a pound,” according to the 1961 “Chronicles of San Quentin” by Kenneth Lamott.

When he was 50 years old, he resigned his prison post.

“To the Hon. J. P. Ames, Warden California State Prison — Honorable sir : Grateful to you for your kindness toward me since your connection with this institution, hoping you are satisfied with my conduct as an officer under your charge, believing you will at least say that I have endeavored to do my duty honestly, faithfully and fearlessly. I beg of you to accept my resignation as Captain of the Yard of this institution, to take effect to-day. Respectfully, AC McAllister,” reported the Daily Alta California, June 6, 1880.

But when new management came on the scene in 1883, McAllister was asked to return as Captain of the Yard under Warden Paul Shirley. He remained until 1885, when his position was merged with that of turnkey, assumed by Charles Aull.

McAllister’s dismissal by the prison Board of Directors riled many. An editorial in the Marin Journal dated June 18, 1885, questioned the wisdom of terminating McAllister along with three correctional officer positions. The staffing reduction was part of a cost-saving measure, the newspaper reported.

“Notwithstanding over 1,000 hardened criminals are confined within the walls of San Quentin, the public have, during late years at least, enjoyed almost a perfect security against any danger of a ‘break.’ Very largely this feeling of security has been brought about by the public confidence in the experienced officers and guards employed to secure the utmost safety. Captain McAllister, as is generally known, held the responsible position of Captain of the Yard for four years under the wardenship of (Lt.) Gov. Jim Johnson, and has held a like position for two years under the present administration. Under (Lt.) Gov. Johnson’s management, it was conceded by those high in authority that Capt. McAllister distinguished himself as a prison disciplinarian.”

Serving the homeless

McAllister was appointed to run the new Marin County Poor Farm, which opened in 1880 to serve the homeless population. He wasn’t the only San Quentin employee to find work at the new farm. Prison physician Dr. A.W. Taliaferro also served the new institution.

While a farm might sound easier, working on those 94,000 acres presented other dangers.

“While repairing the water tank trestle he missed his footing and fell a distance of about 10 feet,” reported the Marin Journal, April 7, 1892. “In his fall, he grasped one of the stanchions of the trestle and his arm was wrenched from its socket.” A later report said his arm was broken in two places.

In 1893, despite a petition bearing many signatures requesting McAllister remain in his post, the county board of supervisors requested his resignation.

“The ax was raised in the supervisors’ room on Monday as soon as they assembled, and when it fell, it landed on Archie McAllister,” reported the Marin Journal, April 6, 1893. “McAllister’s letter of resignation, as requested by the board, was then read.”

He had been the superintendent of the county poor farm for seven years.

McAlister spent most of his adult life in public service. After his prison career, he was the superintendent of the county farm and for “several years before his death, he held a position in the (US) mint (in San Francisco),” reported the reported the Marin County Tocsin, July 2, 1910.

The personal side of McAllister

McAllister earned some ink in newspapers when he offered to sell a machine based on an infamous cow.

“Archie McAllister hasn’t got an elephant on his hands, but has something next door to it in the shape of Mrs. O’Leary’s cow which caused the Chicago fire. The animal is stuffed and is supplied with some sort of paraphernalia which allows ice-cold milk to be drawn off. Archie will sell the cow dirt cheap,” reported the Marin Journal, March 1, 1894.

When two of his children passed away, their headstones were vandalized.

“One of the most contemptible pieces of vandalism ever committed in this city occurred in the old cemetery on E street when some miscreant, armed with a hammer, smashed the headstones and granite work on the graves where lie the remains of Captain Archie McAlister’s two children. Capt. McAlister has no enemies here,” reported the Marin County Tocsin, July 7, 1906.

He was 80 years old when he died in 1910, buried in Mt. Tamalpais Cemetery. He was survived by his wife, Kate McAllister, and three daughters – Frances Dunn, Anna and Alice McAllister.

“The deceased was a man of sterling worth and unquestioned integrity. He led a good life and passes on life’s highway leaving behind him a spotless reputation,” according to the Mill Valley Independent, July 1, 1910.

Lamott’s 1961 book closes by noting what’s been lost through the years.

“The Garden Beautiful is gone, and so is the Porch, and with it the last physical reminder of the old women’s department and such fabled captains of the yard as ‘Rough-house’ New, ‘Sammy’ Randolph, John Edgar and McAllister,” wrote Lamott.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.