A 1928 report on the education, library, religious activities and women’s department highlights the successes of early rehabilitation efforts.

San Quentin prison staff worked to carry on the rehabilitative mission started by earlier wardens. The document, a report to Warden James B. Holohan, is one of many showing the prison system’s evolution from breaking rocks to cracking open books.

The report ends by echoing the modern mission of rehabilitation through job training and education. As the report states, “the lack of (job skills and education means) that we have an obligation to make it possible for the men to (prepare for) careers when they return to society.”

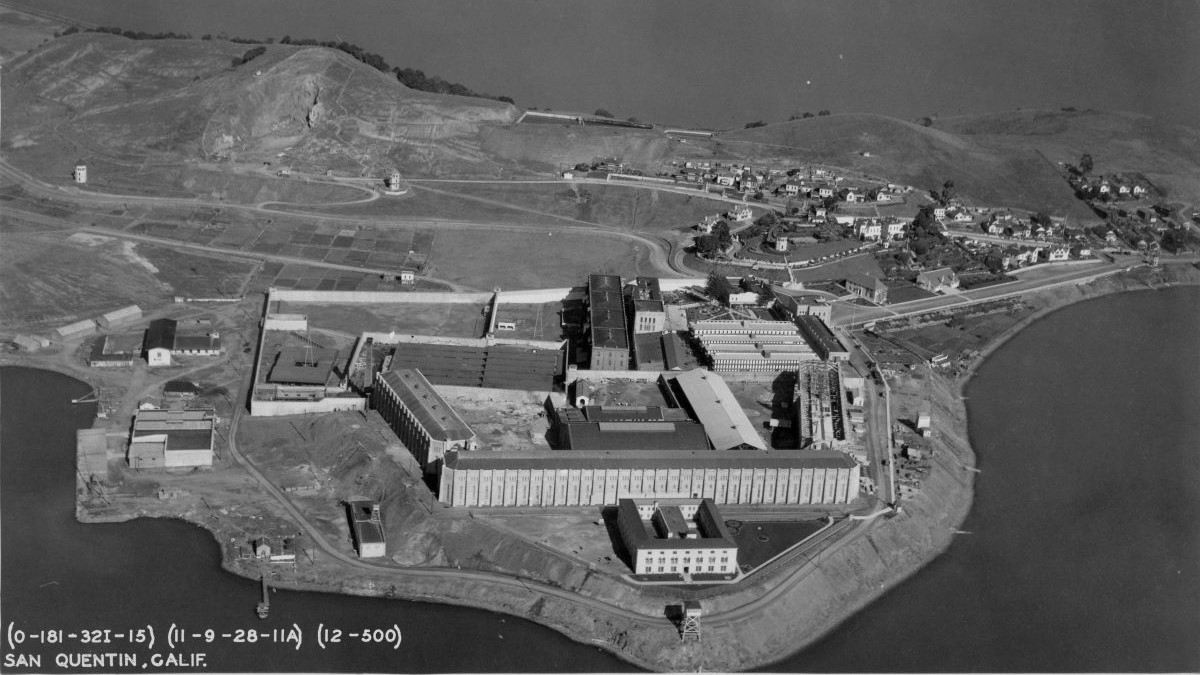

Improvements at San Quentin

“The space used for the Library and Chapel and Educational Work has been remodeled. Activities centering there are carried on much more efficiently than previous,” the July 1, 1928, report states. “The space is being used up to its maximum and we greatly need additional space.

“During the biennium, the prison population increased 34%. The increase in bona fide enrollments in educational work was 93%. All educational activities are voluntary. The completion of the new Women’s Prison has made it possible for many of the women to take up studies. Approximately 35% of the women are taking correspondence instruction under the direction of this department.”

San Quentin honor camps

Much like today’s conservation camps, many worked at the “new road camps” to build highways across California.

“Since the establishment of the new road camps, some of the men there have continued their studies. There are students in every one of the seven camps. In two camps, men who taught here have organized classes (offered) after work on Sunday,” the report states.

“Instruction at San Quentin is given in classes and by means of correspondence by (incarcerated) assistants. Classes are (held) in the chapel five afternoons a week. The men having the least formal schooling (can progress to a point where they can) continue their studies in correspondence courses. The instruction is planned for short-unit courses of 12 weeks. (There is) an intermission of one week following the completion of each term. Thus, we operate throughout the year. In the six terms which we have been operating under this plan, our chapel classes have enrolled 381. Overall, 70% have completed the prescribed courses. Completions would have been (higher) but (shifting) to road camps, paroles and discharges have (caused) men to discontinue their studies,” according to the report.

More advanced studies were offered Saturday afternoons and Sunday mornings. Subjects included English, shop arithmetic, electricity, algebra, trigonometry, navigation, soil management, vegetable gardening and dairy management. Classes in foreign languages were also offered such as “conversational French, German and Spanish. Spanish is by far the most popular. (Also,) 119 Spanish speaking inmates have (learned enough) English they can speak and read English fairly well.”

Local correspondence classes, dubbed Letter Box Courses, offered:

- arithmetic

- English

- geography

- English for Spanish-speaking people

- Spanish

- civics

- orthography

- penmanship

- soil management

- vegetable gardening

- and dairy management.

Students range from 20 to 67 years old with the average level of formal school being seven years.

Job skills and return to society

“Comparatively few (inmates) have been trained in any business, profession or trade requiring preparation comparable to trade apprenticeship. Take this fact in connection with the lack of (education) and it becomes evident that we have here an opportunity, and, an obligation to the state, to make it possible for the men to fit themselves for more useful careers when they return to society,” according to the report.

“Probably more than 90% of the men now in San Quentin will be returned to society after collectively spending, as a minimum, more than 15,000 years of time here. It is possible for them to go back better trained mentally, manually and morally. It is possible to so connect up our present prison industries and the educational work that they may work as a constructive whole.”

The report also advocated the hiring of vocational teachers.

“(This approach) would require vocational teachers who can make job-analyses of industrial work and establish checking-levels to insure that individuals shall be trained systematically in that work. Without the addition of a single industry, it is possible to analyze several of our industries so that they can be conducted on a trade basis. The expense connected with such a project would be a trifle when the social benefit is considered. To make a beginning in this work, two vocational teachers could be secured,” the report states.

Recommendations from 1928 reformers

“In order that the possibilities of training far better citizenship may be realized and extended, and that our obligation to the state may be met, so that the man in confinement and the social order to which he will return both may profit, I make the following recommendations:

- That illiterates be required, as the first duty, to acquire a working knowledge of the fundamental tools of education;

- That men unskilled in any business or trade be required to acquire some skill that will contribute to their economic efficiency;

- That adequate facilities for the realization of, consisting of

- a building capable of housing the activities of the classes, the libraries, and for use for religious, educational and other inspirational purposes;

- a corps of certified teachers to conduct the classes and vocational activities.

- That a beginning in this larger program be made by securing two additional teachers for the next fiscal year.”

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Office of Public and Employee Communications

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.