(Inside CDCR takes a closer look at Charley Parkhurst, a gender-nonconforming stagecoach driver who helped transport early criminals to prison.)

Today’s CDCR transportation units rely on buses and cars traveling over paved roadways, but this wasn’t always the case. When transporting inmates in the 1850s, there were generally two methods – ship or stagecoach. One of the state’s early stagecoach “whips,” as drivers were called, was “Six-Horse Charley” Parkhurst.

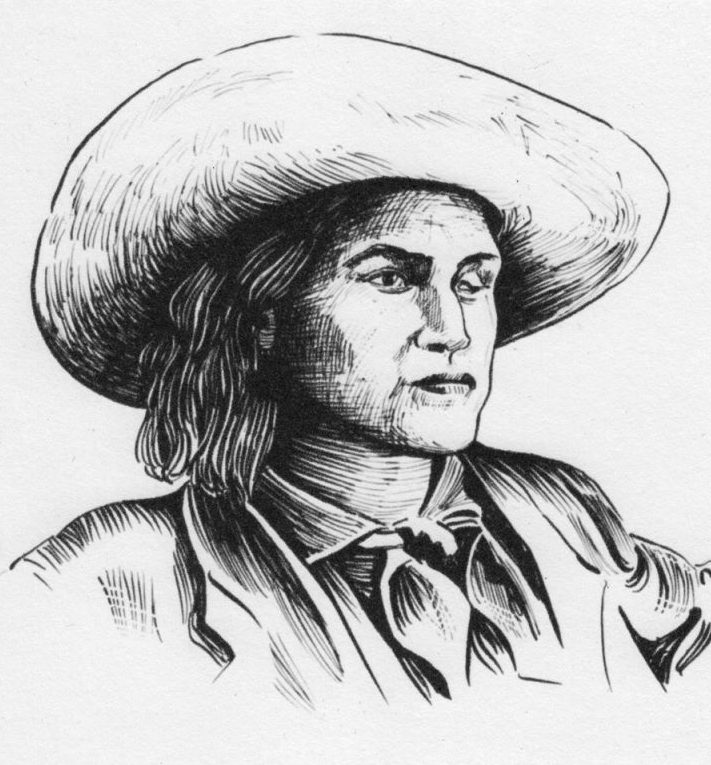

The cigar-smoking, tobacco-chewing whip drove stages in northern California, Nevada and sometimes across multiple states. He was ranked among the best drivers in California, alongside Henry J. “Hank” Monk and Clark Foss. He helped transport patients to the state asylums as well as the state prison at San Quentin. Parkhurst was a sort of early contracted Transportation Officer. Parkhurst’s stage driving career ended when trains began to crisscross the state.

He retired from the road, occasionally hauling something for neighbors, but got into the lumber and ranching business. Decades of hard living finally caught up to Parkhurst, who succumbed to cancer in 1879. It was only then friends discovered Charley’s given name was Charlotte and he’d been born female.

This is the story of a person who migrated west during the Gold Rush to blaze new trails, break stereotypes and live life on his own terms.

From orphan to stagecoach driver

Born in Vermont in 1812, Charley Parkhurst lost both parents at an early age. He was placed in an orphanage along with his siblings. Chafing under the controlling reins of an institutional environment, the young Parkhurst swiped boy’s clothing and ran away. Many accounts claim he sought excitement, freedom and the opportunities only afforded men at that time.

The Providence, R.I. Journal provided a glimpse into Parkhurst’s early life, reprinted in the Santa Cruz Sentinel, February 21, 1880.

“He discovered boys have a great advantage over girls in the battle of life and desired to become a boy. He borrowed a suit of boy’s clothes and (fled) with them from the (orphanage). In the character of a boy, he went to work in Ebenezer Balch’s stable at Worcester, and remained there until Balch moved to Providence. Charley had proved himself faithful and efficient, (so) Balch brought him to the What Cheer stables. Charley soon became an expert whip. His judgment as to what could and what could not be done with a wagon was always sound. (Also,) his pleasant manner won him friends everywhere. He was fond of a six-in-hand (six-horse team).”

Already a successful stagecoach driver, Parkhurst heard exciting tales of opportunity in California. Some of his fellow coachmen re-established themselves in California, providing much-needed transportation during the Gold Rush. Parkhurst soon followed. He took a job with the new California Stage Company, started by some of his former coworkers. At the time, the only way to reach the gold field was by foot or hoof. The most efficient method was the stagecoach. He started running stage lines around the San Francisco Bay area and the Sierra foothills.

Using stagecoach services, county sheriffs transported convicts from their county jails to San Quentin. Some took the last part of their journey by steamships traveling the rivers or the coast. According to some accounts, Parkhurst even landed a few bandits in prison himself.

“Parkhurst waged a war upon the outlaws (along) the route of the Grass Valley stage,” according to Munsey’s Magazine, 1901. “It has been written that Parkhurst was never held up. (While) probably a mistake, he was remarkably successful in his encounters with the men who tried to stop him. He was small, but full of nerve and resource. Once a robber halted him as he was lashing his horses through a mud hole that threatened to bog him down. Parkhurst’s whip was in the air when the robber sprang out of the brush. Down came the lash across the road agent’s eyes. The fellow was picked up a day later, utterly blinded (but) they saved (one) eye so he could see well enough to pick jute during his term in (San Quentin).”

According to National Geographic Magazine published in October 1896, stage drivers were popular in the community.

“For the first 20 years in the history of California the only mode of transportation after leaving the navigable rivers and the coast, aside from walking, was by stagecoach, wagon, pack-mules (and) horses. In Sacramento and Marysville, the two principal steamboat landings, it was a daily occurrence to have to depart at break of day 50 or more stagecoaches and wagons loaded with passengers bound for the different mining towns and camps in the foothills and mountains,” reported the magazine.

“The return stages were so scheduled that they arrived back late in the afternoon or evening (so they) would be ready to leave again the following morning. The early stage-driver in California was perhaps the most unique and was certainly one of the most important personages in the community. His social standing and influence were rated (by the number of horses so) a six-horse stage-driver (was equivalent) to a mayor or governor.”

Roads were ‘Little more than trails’

The conditions endured by drivers and passengers could be dangerous. Parkhurst traveled at night, through rain or snow, and used mud-wagons when the roads were nearly impassable.

Samuel Clemens, aka Mark Twain, recounted his 1864 stagecoach experience in his book, “Roughing It.”

“(Shortly after waking in the coach and getting dressed,) the driver sent the weird music of his bugle winding over the grassy solitudes, and presently we detected a low hut or two in the distance. Then the rattling of the coach, the clatter of our six horses’ hoofs, and the driver’s crisp commands, awoke to a louder and stronger emphasis. We went sweeping down on the station at our smartest speed. It was fascinating — that old overland stagecoaching,” Twain recalled.

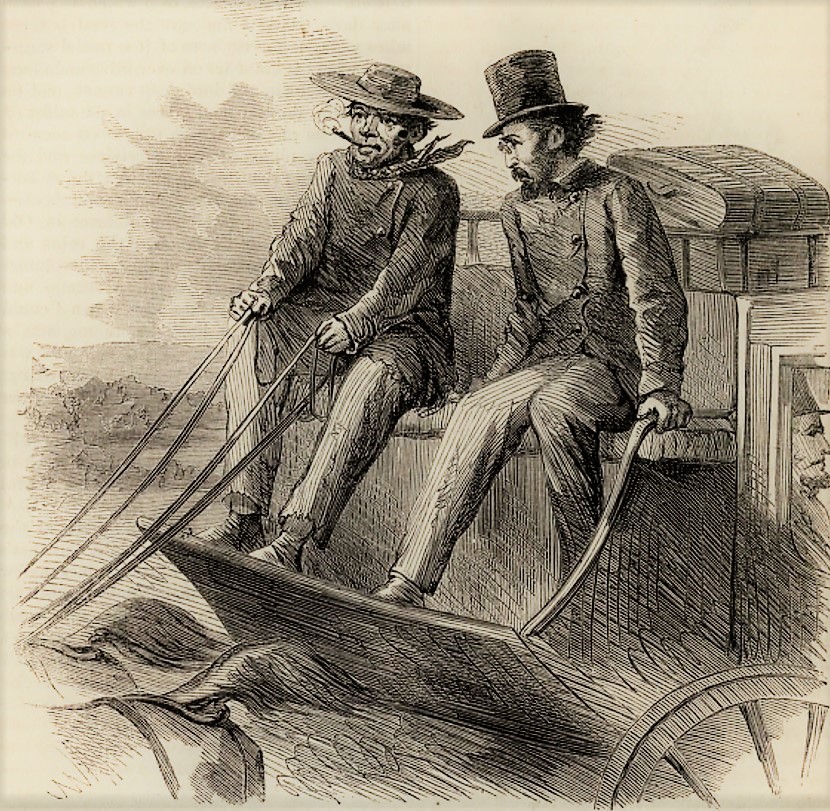

“It was drawn by six handsome horses, and by the side of the driver sat the ‘conductor,’ the legitimate captain of the craft; for it was his business to take charge and care of the mails, baggage, express matter, and passengers. We three were the only passengers, this trip. We sat on the back seat, inside. About all the rest of the coach was full of mail bags — for we had three days’ delayed mails with us. Almost touching our knees, a perpendicular wall of mail matter rose up to the roof. There was a great pile of it strapped on top of the stage, and both the fore and hind boots were full.”

Stagecoach jostles a journalist

Journalist John Ross Browne caught one of Parkhurst’s stages in 1864, which he documented in Harper’s Monthly Magazine a year later. Seated beside the crusty stagecoach driver, Browne had plenty of questions. Throughout the tale, he refers to the driver as “Charlie.”

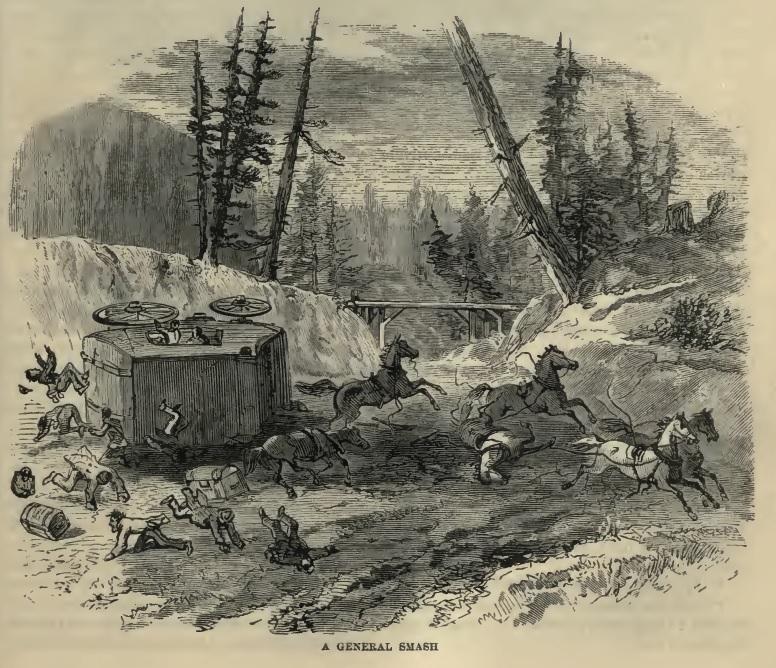

“‘Do many people get killed on this route?’ said I to Charlie, as we made a sudden lurch in the dark and bowled along the edge of a fearful precipice. … ‘Some of the drivers mashes ’em once in a while, but that’s whisky or bad drivin’. Last summer a few stages went over the grade, but nobody was hurt bad – only a few legs (and) arms broken. Them was opposition stages. … Some of the opposition boys did it last summer; but our company’s very strict. They won’t keep driver, as a general thing, that gets drunk and mashes up stages. … A stage is worth more than two thousand dollars.’”

Parkhurst explained the methods he used to drive stage in the dark over steep and rough mountain passes.

“Fact is I’ve traveled over these mountains so often I can tell where the road is by the sound of the wheels. When they rattle, I’m on hard ground; when they don’t rattle, I generally look over the side to see where she’s a going,” he said. “I calculate to quit the business next trip. I’m getting well on in years … and don’t like it so well as I used to, before I was busted in.”

By busted in, he was referring to broken ribs received a few years earlier when he “mashed,” or overturned, his coach on a sharp curve. In yet another trip, a horse kicked Parkhurst, causing him to lose an eye. This earned him the nickname “One-Eyed” Charley.

Newspaper reporter George F. Weeks, afflicted with tuberculosis, came west in 1876 to seek relief for his condition. Some 50 years later, he was encouraged to jot down his memories. By the 1920s, railroads and automobiles had replaced stagecoaches, but his descriptions of stage travel colorfully describe the challenges faced by passenger and drivers.

“Gone are the rough, stony, rutty, crooked, steep … roads, little more than trails hewed and hacked from hill and mountain side, or hub deep with drifting sands of the desert. Gone, all gone! Only their memory remains,” wrote Weeks in 1928, who later became the owner and publisher of several newspapers.

“They have given way to the high-priced, ornamental auto stage, well and even luxuriantly equipped in every respect, moving rapidly and comfortably over wide and smoothly paved roadways, whether on mountain or in desert, covering in an incredibly small number of hours the distance that it once required days to accomplish.

“Naught does the younger generation of today know of the old-time stagecoach traffic. And few enough are now living who were obliged to resort to that method of travel when necessity drove, for of a surety few, if any, ever undertook such journeys merely for pleasure.”

In the traffic hubs of Sacramento, Stockton and Marysville “were centered the stage routes leading to the northern, the southern, and the intermediate mining regions, from the far-off Trinity and Klamath, to the headwaters of the Feather, the American, the Yuba, and their various forks, the San Joaquin and its tributaries,” Weeks wrote.

Rough roads in the West

Another trip proved extremely bumpy for the writer. The rough roads caused physical problems for those driving and traveling by stage.

“I was going from Grant’s Pass, Oregon, to Crescent City, California, a journey of two nights and two days over the mountains and through the great redwood forests. I was the only passenger. The road across the mountains was crude and rough. It was not much traveled, and was full of stones and stumps and humps and hollows. I had never before been over such a bad road, and the driver at last told me that I was likely to have serious physical trouble unless I ‘held myself’ as he did when the road was rough – leaning forward with the lower part of my arms resting on my legs and relaxing my body completely, letting it sway and move with every jar and jolt of the coach,” he wrote.

“I should not try to hold myself rigid as I had been doing, by bracing my feet against the bottom of the dashboard and my body against the back of the seat. Once before I had taken a long stagecoach journey of five days and four nights, and at the end had to stay in bed several days before I was able to walk around. But (after learning this method), such a thing never happened to me again.”

When British writer J.G. Player-Frowd wrote “Six Months in California” in 1872, he also traveled by stagecoach through much of the mountain areas.

“Indeed, from Sacramento many very crack stages started daily, with their six horses, driven by Western men, who would go down the mountain roads full gallop, and, unless anything broke, would take you safely a long way up the opposite slope without hardly slackening their speed. The Western stage-driver (has) iron nerve and rough coarse manners. Reckless, and daring, he is yet more to be trusted than a less bold and more cautious driver.

“The only way to go down those mountain grades is to rush it. The turns in the road are so sharp, and the incline so steep, that to venture timidly is to risk upsetting the coach. Sometimes, at a bend in the road, the leaders’ heads, when there are six horses, will almost look into the windows of the stage. (Meanwhile,) there sits the driver, with one foot firmly pressed on the break, his horses well in hand, taking them round the corners,” he wrote.

The writer was not a fan of stagecoach travel.

“I recommend all travelers … have as little to do with stages as possible. The roads are rough and dusty. … In short a stage journey is an infliction to be borne in order to travel from one place to another; you are choked with the dust, starved by the dirt and badness of the meals, wearied with the ceaseless jolting, and bored to death by the monotony of the scenery,” Player-Frowd wrote.

Parkhurst’s later years

“I’m no better now than when I commenced. Pay’s small and work’s heavy. I’m getting old. Rheumatism in my bones – nobody to look out for old, used‐up stage drivers. I’ll kick the bucket one of these days and that’ll be the last of old Charley,” he told Browne.

A decade later, as improved roads and interconnected railroads began to crisscross the state, Parkhurst gave up the six-in-hand reins.

“By 1873 the railroad was rapidly replacing the stagecoach and consequently Charley Parkhurst gave up his line. For a while, (he) operated a horse changing station about halfway between Santa Cruz and Watsonville. This enterprise was later given up for a cattle raising operation. By 1876, Charley had become a tired old man – 64 years old – crippled with rheumatism to the point of deformity,” said Edward Pfingst, May 24, 1958.

He eventually sold his property and moved into a small cabin on the Moss Ranch, owned by the Harman family, about 60 miles north of Watsonville on the Santa Cruz Road.

Parkhurst retires, falling ill

“After over 30 years as a rugged (stage driver), Charley retired with such high praise as the ‘best damn driver in the West.’ (While staying with the) Harman family, several (time he said) he had something to tell them but kept postponing. Eventually it was too late as he could no longer talk.

“During the early part of 1879, Charley complained of a continuous sore throat. He was urged to see a doctor but he would have none of it,” said Pfingst during his 1958 lecture. “The story is that whenever Charley felt sick, he treated himself using the same remedy he (used) on his horses. (Otherwise, he used) the same medicine friends used for what could be a like (condition). (Unfortunately,) none had any effect. His ailment grew gradually worse, however. He finally consented to be taken to Soquel, (where he was diagnosed with) cancer of the tongue and throat. (An operation was) recommended (to insert) a silver tube or pipe in his throat but Charley refused. Gradually he became weaker and he died December 28, 1879.”

Birth gender revealed after death

While preparing his body for burial, his birth gender was revealed. Parkhurst lived his life as a man, in the body of a woman. Some news reports on the revelation could be considered ahead of their time.

“In (Parkhurst’s) case, it is evident the masculine character is present in the fullest sense. Such a woman is very much more a man than anything else. In adopting male clothing and habits, she only obeys the law of her nature, which is in such cases no doubt the safest guide,” according to The Record-Union, Jan. 3, 1880.

In an opinion piece published in Rhode Island, the paper defended Parkhurst and others like him.

“The only people disturbed by the career of Charley Parkhurst are the gentlemen who have so much to say about ‘woman’s sphere’ and ‘the weaker (sex).’ It is beyond question that one of the most expert drivers in this state, and most celebrated of the world-famed California stage drivers, was a woman.”

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Read more about others who helped shaped today’s CDCR such as Artie Baker and Rattlesnake Dick or explore the department’s history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.