As a young man, Robert Eugene Russell crossed the country with explorer John C. Fremont, helped lead a group of besieged soldiers to safety, was witness to the first session of the state Legislature, testified in a court-martial in Washington, D.C., and later worked as a guard at San Quentin.

He was a California pioneer trying to step out of the overpowering shadow cast by his father. This is the story of a soldier, mountaineer and early prison guard.

Lost in a legacy

Colonel William Henry Russell, father of R.E. Russell, cut a broad swathe in the history of California as well as the nation.

“He was a member of the Legislature of (Kentucky) in 1830; and was mainly instrumental in securing the election of (Henry) Clay, an old political opponent, to the U.S. Senate in 1831; so acknowledged by Mr. Clay himself,” wrote Robert J. Walker in an 1867 letter to U.S. President Andrew Johnson, recommending the colonel for appointment to the post of U.S. Consul-General in Havana, Cuba.

“In 1846, he went to California at the head of a large emigration. … In 1849, Col. Russell returned to California, where he was made an honorary member with Gov. Waller of the Convention that framed the State Constitution. In 1851, he was appointed Collector of Customs at Monterey,” Walker wrote.

“In 1861, he was appointed by (President) Lincoln (to) U.S. Consul at Trinidad de Cuba, which office he held until (the president’s) assassination.”

The elder Russell also served as a U.S. Marshal. The younger Russell had a role model in his father, but also had big shoes to fill.

Young solider refuses to surrender

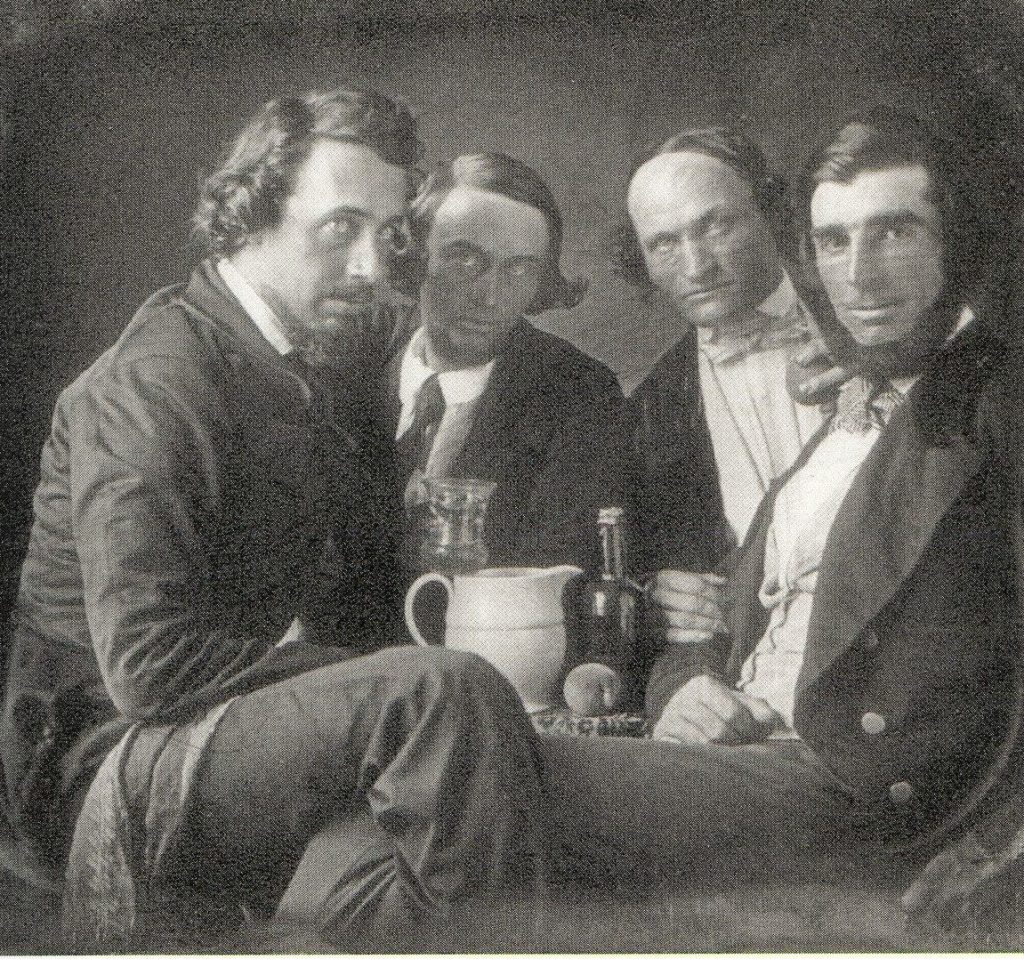

Along with his father, R.E. “Gene” Russell served under John C. Fremont.

“In 1845, Eugene Russell joined Fremont’s topographical engineers and came out to California. (After war was declared against Mexico), he was transferred to Fremont’s mounted battalion, volunteers,” reported the San Francisco Call, reflecting on his life, June 14, 1894.

At Santa Barbara in 1846, R.E. Russell was part of a nine-member garrison, commanded by Lt. Talbot. As Manuel Garfias and his 200-strong army marched from recently recaptured Los Angeles, locals rushed to warn the Americans. The Los Angeles garrison had surrendered, turning over their weapons and agreeing to remain under surveillance.

Garfias sent word he wanted the Santa Barbara garrison to surrender, hand over their weapons and remain “on parole,” just as the Los Angeles unit had done. The soldiers had other ideas.

The 22-year-old Russell refused to surrender and persuaded his fellow soldiers to head for the hills.

“All the men but one, Russell, favored surrender at first; but as he declared his purpose to escape, the rest concluded to go with him,” according to History of California by Hubert Howe Bancroft.

“Talbot and his men decided to (retreat) and thus avoid the necessity of a parole. They started at once, met with no opposition … and gained the mountains (Sept. 27, 1846). They were experienced mountaineers. … They remained a week in sight of the town, thinking that a (U.S. naval) man-of-war might appear to retake the post. Their presence was revealed … by their attempts to obtain cattle and sheep at night.”

American soldiers harass the enemy

Enemy forces tried to flush out the soldiers, coming so close at one point, “a horse was killed by a rifle-ball.”

Walter Colton, at Monterey, wrote about the garrison’s journey in his book “Three Years in California.”

“The guard of ten, commanded by Lt. T. Talbot, and posted at Santa Barbara to maintain the American flag, arrived here last evening. When the insurrection broke out at the south, they were summoned by some two hundred … to surrender,” Colton wrote in his journal dated Nov. 9, 1846. “They contrived, however, under cover of night, to effect their escape. Their first halt was in a thicket, to which they were pursued by some fifty of the enemy on horseback. They waited (until) the foe was within good rifle shot, and then discharged their pieces with terrific effect.”

The Americans drove off their pursuers, at least for a brief period, so the small garrison pushed east “several leagues … and gained a new ambush.”

“(The army) rode here and there, penetrating every thicket, but the right one, and to prevent their escape at night, set fire to the woods. But one ravine, overhung with green pines, covered them with its mantling shadows; through this they made their noiseless escape,” Colton wrote.

Rough journey to safety

“Fire was set to the mountain chaparral, with a view to drive them out,” Bancroft’s history book states. “They crossed the mountains, receiving aid and guidance from a Spanish ranchero, reached the Tulares, and proceeded to Monterey, where they arrived Nov. 8, having suffered many hardships on the long journey.”

Colton’s journal reveals much more of the story.

“(On their trek to Monterey,) they suffered greatly from hunger and thirst: the rugged steeps, among which they were straying, yielded neither streams nor game,” Colton wrote.

Eventually, the crew met a friendly ranchero who guided them over the hills and into the hands of a friendly band of Native Americans, who fed the starving men and tended to their wounds.

“Lieut. Talbot and party, guided by Indians, now held their course through the valley of the San Joaquin. Their progress was delayed by the sickness of one of their companions, whom they were obliged to carry on a litter. They subsisted entirely on the wild game which they killed,” Colton wrote. “They were all on foot; and after traveling nearly five hundred miles in this manner, reached Monterey, where they were welcomed to the camp of Col. Fremont with three hearty cheers.”

Defending Fremont

There was a power struggle between Maj. Fremont and Capt. Phillip Kearny, as well as a governorship on the line. Fremont served as Military Governor of California from January to February 1847. Kearny wrested control from Fremont, who fought back with the power of the pen. His leadership claim was complete with a petition signed by many in the fledgling territory, most hailing from the southern region of California.

Kearny alleged Fremont disobeyed direct orders through his actions. On Sept. 17, 1847, Fremont reported to Washington, “calling for the charges against him and demanding an early trial,” according to Bancroft’s book.

The court-martial convened Nov. 2. To testify on behalf of his commander, R.E. Russell traveled to Washington, D.C.

Fremont was convicted of the charges but President Polk commuted his sentence and reinstated him. Fremont resigned from the U.S. Army and moved to Monterey. When California was admitted to the U.S. as a state, Fremont became one of the first two elected senators.

Legislature’s first sergeant-at-arms

After testifying on Fremont’s behalf, Russell returned to California.

“On the first Legislature being held at San Jose (in 1849), he was appointed sergeant-at-arms. At this time he was intimately associated with such old-timers as Joe McKibbin, Col. Henley, James Crawford, Gov. Bigler and Gov. Burnett,” reported the San Francisco Call, June 14, 1894.

With the Gold Rush, Russell tried his hand at mining. According to news accounts, he made “a good deal of money, which he later lost in stocks.”

Called to service

In 1851, when hostilities with Native Americans seemed imminent, a three-company battalion was formed with Russell serving as sergeant-major, under the command of James D. Savage.

“The full complement of organized volunteers, numbering two hundred and four, rank and file, reported to Major Burney at Savage’s old store near Agua Fria, February 10, 1851, equipped, mounted and ready for service. It was known as the Mariposa Battalion,” according to the 1928 book “The Last of the California Rangers.”

For a time, there were peaceful negotiations without the need for military intervention. Then, a group of Native Americans in a “deep valley” sent word they would kill or capture any non-natives who entered their territory.

Commander Savage gave the order to “mount up” and his militia headed for the unknown valley, following small trails.

“Traveling in silence, as instructed, they braved the heavy rains without a qualm. On reaching the South Fork of the Merced River, their efforts were rewarded by the discovery of “Indian signs.” It was very dark, and a terrible blizzard almost blinded them, so they camped here until morning,” according to the book.

The following morning, they left behind their animals with a strong guard and made their way to the village, under the guidance of a Native American. The village was familiar with Commander Savage, having worked for him in the past. They welcomed the group.

Stumbling into Yosemite and taking San Quentin job

The next day, they set out to find the hidden tribe and on May 5, 1851, the first non-native settlers stepped foot in Yosemite Valley.

“To the Mariposa Battalion under the Command of Major James D. Savage is to be accorded the honor of first entering the Yosemite Valley,” according to the authors. “Is it strange that these Indians of the hills and mountains were so unwilling to leave the awe-inspiring wonders of the Great Spirit and go to the plains, where malaria and mosquitoes prevailed, and where an incoming civilization that was to them new and objectionable, was gradually forcing their people away from their life of ‘real nature?”

After a few altercations, the battalion was mustered out of service in July 1851. Savage was killed a short time later, shot through the heart by a man with whom he quarreled.

Now out of the service, and out of a job, he accepted an offer of employment from an old friend – Gen. James Estelle.

Estelle was a fellow veteran of the war with Mexico and in trying to fend off accusations of staff misconduct, the prison contractor tried to recruit professionals to work at the new state prison State Prison at Corte Madera, also known as San Quentin. Russell is listed as a guard at San Quentin as of January 1856, when he was paid $86.

He filled the guard post “efficiently and bravely for three years,” according to the San Francisco Call, June 14, 1894.

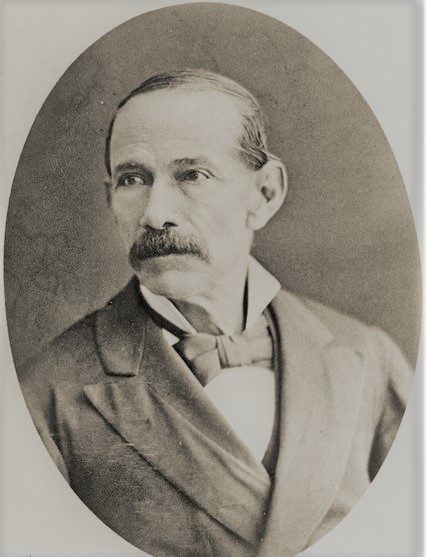

His final years spent in poverty

The old soldier earned an $8-per-month pension for his wartime service. He turned to music, writing and composing songs that proved popular among traveling bands of minstrels.

“He had also considerable talent as a musician, and in his later years, made use of it to eke out his scanty pension,” reported the newspaper. “The composer received very little money for (his songs). But poor as the old man was, he always managed to pay his way honestly.”

Russell passed away June 13, 1894. Penniless and with few close friends, he was 70 years old and never married.

“Robert Eugene Russell, one of California’s earlier timers, will be buried in the National Cemetery. In the days of gold, he was associated with the most prominent men in the land, but poverty caused him to slip out of sight. For many years, only a few faithful friends, not too prosperous themselves, were the only ones who cared to know that the once-dashing soldier of the Mexican war was still in the land of the living,” reported the Call, June 14, 1894.

According to his friend of 50 years, E.J. McCourtney, “Eugene Russell had borne the poverty of his later years while never refusing to others any help in his power.”

On his deathbed, he handed McCourtney as small sum of money and asked him to settle an outstanding debt.

“He left enough to pay it and have a dollar to two over,” the friend told the newspaper.

The last few months of his life left him blind in one eye and suffering from paralysis.

“The disease developed unfavorable symptoms and a fortnight ago he was removed to St. Mary’s Hospital, where he breathed his last on Tuesday,” reported the Call.

He was buried in grave number 477 on the west side of the National Cemetery in San Francisco.

His father, Colonel Russell, died in Washington, D.C., on Oct. 13, 1873.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.