By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

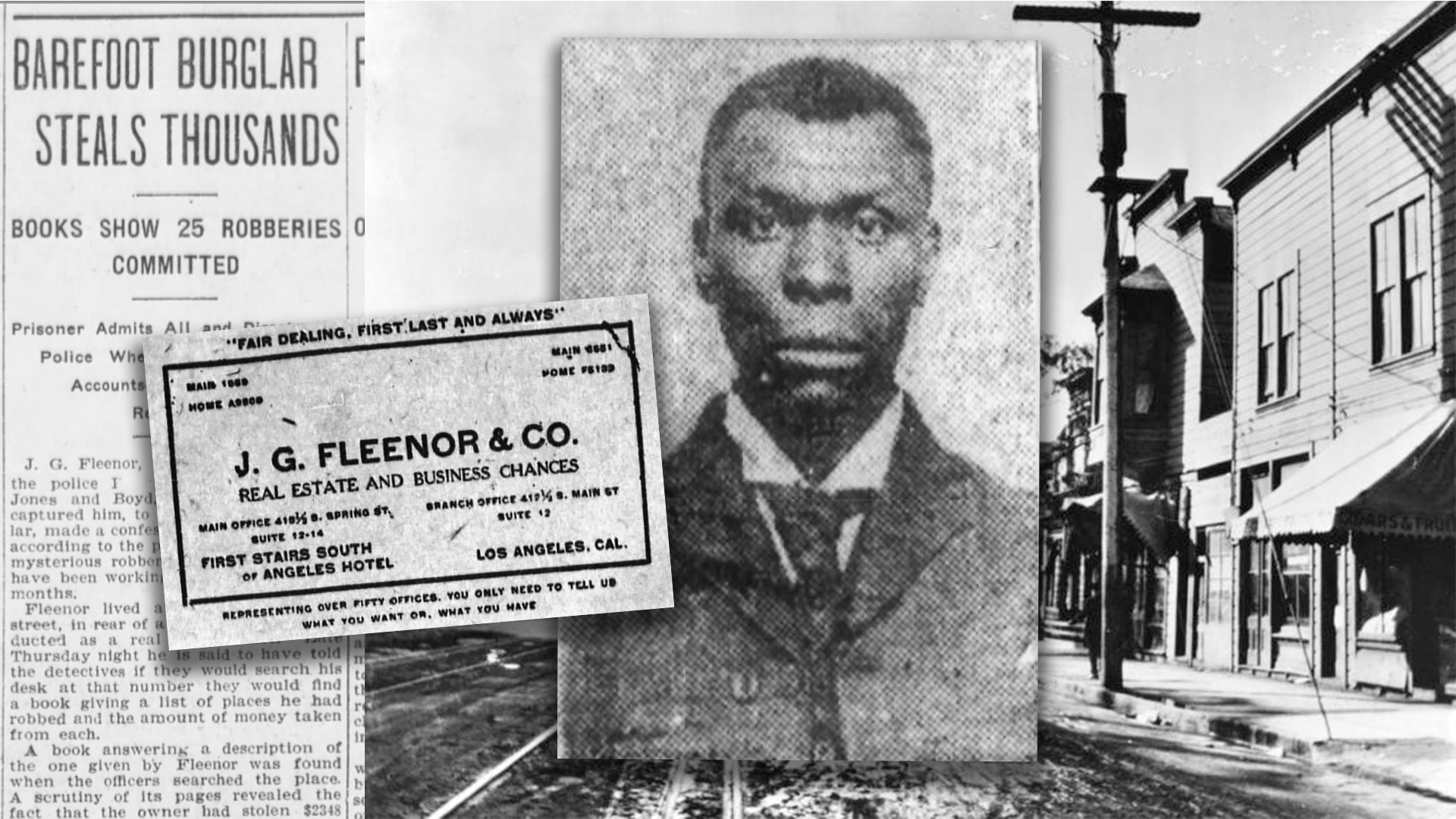

By all appearances, James G. Fleenor was a successful Los Angeles area real estate agent, owning several rental properties. By day, he appraised homes and helped others sell their property. By night, he burgled the homes of those he’d been casing for weeks. In 1905 and 1906, Fleenor burglarized nearly 100 homes. He was arrested, tried and sentenced to 14 years in state prison. This is the story of a seemingly prosperous businessman who was instead a career criminal.

Fleenor wanted more out of life

Fleenor claimed he was the son of a freed slave and raised in a city where non-white families were scarce. He told the press he and his family were still treated fairly in his hometown.

“There were only three families of colored people and we were all thought (well) of by the white people. My mother (took care) of the whole neighborhood,” he told the Los Angeles Times in a 1907 jailhouse interview.

He learned cabinetmaking and soon set out on his own. “I decided I would go out in the world (expecting to) get the same treatment (as my hometown),” he said. “I didn’t know any better.”

What Fleenor found was job discrimination based on the color of his skin.

“In place after place I offered to do a day’s work for nothing, just to show what I could do. People seemed to like me. They wanted to give me work — gardening or shoveling coal or something like that. But, well, how would a lawyer feel if someone offered him a job taking care of chickens?”

He said business owners wanted to hire him, but they feared how others would react.

“Many places I was told they’d like to put me to work but that if they did all their other workers would walk out of the shop. I am not saying anything against the unions but that was how it was. That was all. It was simply the way fate was working with me.”

It’s not clear if Fleenor was truthful in his interview since he had a prior criminal record, as well as an alias, in two other states. He neglected to mention any of this in the various printed versions of his interview.

Had record in Nebraska

This wasn’t Fleenor’s first run-in with the law. Before coming to California, he “operated extensively in Omaha” and was known by the “alias John Wesley Carter,” reported the Omaha Daily Bee, May 21, 1907.

In 1896 he was arrested, tried and convicted of burglary. He was sentenced to 10 years at the Nebraska state prison. Prior to that, he did three years at a state prison in Missouri.

“He worked in his bare feet and thus gained the title of the ‘barefoot burglar,’” reported the Omaha Daily Bee, March 7, 1907.

According to news reports, he had a way with words and often talked his way out of trouble.

According to those familiar with Fleenor, he “had a way of stirring the sympathies of judge and jury … which sometimes won his release,” the paper reported.

Barefoot burglar steps into wrong house

“Conducting a legitimate real estate office during the day and breaking into houses at night was the program carried out for the past two years by Fleenor. His cleverness many times saved him from discovery and his daring many times prevented his capture,” reported the Los Angeles Times, March 1, 1907.

The shoeless prowler finally tripped up Sept. 9, 1906, when he entered the Los Angeles house of a recently retired city official and former councilman.

“The ‘barefooted burglar’ entered the home of Thomas Strohm. The former fire chief was seated upon the front porch and heard a peculiar noise upstairs. He ascended to the second floor and leisurely walked into a front bedroom. At that moment a light was lighted and Strohm saw Fleenor,” the Times wrote. Strohm grappled with the intruder but was overpowered. Fleenor fled with the loot, including an expensive watch that would prove to be his undoing.

“Fleenor was traced to his Main Street (address) through his description obtained by detectives from … Strohm after the latter’s encounter with (Fleenor),” reported the Los Angeles Herald, March 1, 1907.

Given Fleenor’s 6-foot 4-inch frame and reported “giant stature,” detectives made short work of tracing him to the Main Street area. Investigators had far more difficulty connecting Fleenor to the crimes.

“It was through the recovery of Strohm’s watch from a pawnshop several days ago that the police secured (clues) which led to the capture,” reported the Times.

“Fleenor is far more intelligent than the average (burglar),” the Herald reported. “He veiled his actual occupation behind an alleged real estate business and maintained an office at the address where he was captured. He had a large supply of elaborately engraved (business) cards.”

No struggle when arrested

When detectives entered his office, Fleenor offered no resistance. “Well, you’ve got me, fellas,” he said.

“Fleenor lived (on) South Main Street in rear of a place which he conducted as a real estate office,” reported the Los Angeles Herald, March 2, 1906.

As a businessman, Fleenor kept excellent records, including his targets.

“A book … was found when the officers searched the place. A scrutiny of its pages reveal the fact that the owner had stolen $2,348 in money and 25 watches during his stay in Los Angeles,” the paper reported. Fleenor told detectives where they could find some of the loot.

“Detectives yesterday made a more thorough search of the rooms. Inside the window casing they found a number of watches, many rings and several revolvers and razors. Fleenor claimed all the jewelry he had stolen and not disposed of is now in the hands of the officers,” according to the newspaper.

His real estate business brought in enough revenue so Fleenor wasn’t in a rush to relieve himself of the stolen goods.

“Believing that sufficient time had elapsed since the Strohm robbery, Fleenor took the watch to a pawnshop and secured a loan on it. A few days later the police noticed the number of Strohm’s watch on the pawnshop files,” reported the Times.

Fleenor had two offices and both contained hidden loot from his robberies.

The trial made headlines for months.

Vows to escape

While in Los Angeles County Jail, he enlisted the help of two other inmates to try to escape.

“Ernest G. Stackpole, convicted murderer; James G. Fleenor, ex-convict and burglar; and William Borne, burglar with prior convictions on the same charge, regarded as the three most desperate prisoners in the county jail, were surprised (trying to escape at) 1:30 this morning by George Gallagher and Oscar Norrell, the guards on duty. (During) the fight which ensued, the prisoners armed with iron bars and the officers with 38-caliber revolvers, Fleenor was wounded in the head and Borne was shot through the hand,” reported the San Bernardino County Sun, April 5, 1907.

The three hatched their plan when they were transferred to a holding tank to separate them from the general population.

Fleenor broke off a piece of plumbing pipe. To keep water from spraying into his cell, he stuffed the busted plumbing with soap and rags.

“With this piece of pipe, he reached through the bars of the cell and wrenched a large padlock loose, giving him access to the corridor of the cell, which is not more than 15 feet square. Free himself, Fleenor pried off the lock on Stackpole’s cell and the three men set to work to tear down the masonry and wood about the window. By 1 o’clock in the morning, working intermittently between the visits of the guards, they had torn away the window casing, weights and much of the brick work,” the paper reported.

Gunshot in the dark

That’s when the two officers arrived. The area was dark but the officers heard sounds and figured something was amiss.

“The lights were out and the officers shifted carefully to the right, hugging the wall. ‘Grab him now,’ Gallagher heard a voice behind the door whisper. Fleenor … lunged at Norrell,” the paper reported.

Norrell fired a shot, grazing Fleenor’s forehead and going through Borne’s hand. Just one shot was fired and the men surrendered.

Fleenor slips custody

On his way to San Quentin to serve his 14-year sentence, the Los Angeles deputies lodged Fleenor in the San Francisco Harbor Police Station for a quick overnight stay. The deputies expected to get started across the bay early the following morning to deliver their prisoner. One of those deputies was Martin Aguirre, former warden at San Quentin and longtime sheriff in Los Angeles. After a stint in El Salvador supervising prison construction there, he had returned to Los Angeles to serve as a deputy.

Aguirre impressed upon the police the importance of keeping a close eye on Fleenor. The officer took offense at the suggestion that they were in any way lacking for security. With assurances made, Aguirre and the other deputy turned in for the night, confident their man would be waiting for them in the morning.

By 1:40 a.m., Fleenor was gone, having used a bench to pry open his cell door.

Talks to officer outside jail

An officer was returning to the jail at the time and saw Fleenor calmly walk into the night. The officer spoke to the man but generally paid him no attention. When he made his way inside, he asked another officer how their new prisoner made bail.

That’s when the alarm was sounded and a posse formed. Fleenor still managed to make it to the railroad depot and hop a train. Unfortunately for Fleenor, that train wasn’t heading north or east, it was headed south.

“I was fair about the whole thing,” Fleenor told the Times. “When the officers left (Los Angeles) I told them I would escape but they (didn’t) realize I meant what I said. When they placed me in that cell in San Francisco station, I walked about and inspected it. Awaiting my time, I pried open the door. Walking out I met an officer and he stopped to talk. I was in an awful hurry but I did not let him know it and after he talked to me for a minute, I walked out of the driveway, took a car and went directly to the railroad yards.”

When he arrived in Los Angeles, he swiped some blankets. Approached by rookie police officer Ray Robbins, Fleenor feigned drunkenness and gave the name George Thompson.

“On a charge of suspicion, Fleenor was taken to the city jail. As the patrol wagon pulled into central station, Fleenor leaped out and made a dash for liberty. Patrolman Jarvis started after him and caught him. Fleenor offered no resistance,” reported the Times, May 20, 1907.

He was booked into the city jail’s drunk tank.

Hopped the wrong train

For 24 hours, Fleenor went unrecognized until jailer O.L. Gilpin identified him. He was immediately removed and sent to the county jail for transport to San Quentin. Many had theories regarding why Fleenor returned to Los Angeles, some claiming it was for the love of a woman.

“I am not going to prison of my own consent,” Fleenor told the press. “If officers do get me there, the guards will have a hard time keeping me.”

Fleenor said he had not intended to return to Los Angeles, denying any love interest gossip.

As for accidentally returning to Los Angeles, he said he “simply jumped the first freight train I could find after breaking out of the northern jail and I did not know where that train was going. As luck would have it, I arrived in Los Angeles, the last place on earth I wanted to come to. I don’t want to kill any one and Sheriff Hammel has treated me well since I have been here. He will have to keep a close watch over me on the trip north, though, for I will lose no chance to escape.”

The second trip proved easier as the sheriff and Deputy Aguirre delivered him to San Quentin. Despite vowing to escape the state prison, a news report in 1914 indicates he was still serving his sentence.

Other barefoot burglars

- George Ward was sentenced to 20 years at Folsom Prison after a string of Oakland burglaries. Ward earned the nickname “The Barefoot Burglar” because he “worked without shoes,” reported the San Francisco Call, July 12, 1913. “He told the police of entering rooms in which people were asleep and taking money … and escaping. In several instances he climbed to a window, (using) a long-handled rake to hook trousers and other garments from rooms, rifling the pockets and making his escape,” reported the Oakland Tribune, June 7, 1913. His total haul was roughly $1,800 from 28 burglaries. He previously served a 30-year sentence in Alabama but escaped and fled to California, where he continued his criminal pursuits.

- Harry McDonald, a former French correspondent for the Western Canadian Coal Company, “confessed to having entered 12 homes in Los Angeles. In each case the police declare that they had found traces of his bare feet,” reported the Oakland Tribune, Nov. 5, 1914.

- Walter Zelenick, 23, used his crimes as an alibi against similar heists in Oakland, Berkeley and Alameda. “He admitted copying the idea from the phantom prowler (in Oakland but said), ‘You can’t pin those jobs on me. The same nights that fellow was robbing places in Oakland, I was in San Francisco robbing places,” reported the Oakland Tribune, May 23, 1940.

- Rudolph V. Holly, “known as the ‘barefoot burglar’ because his footprints were found at the scenes of many of his jobs last year, … told police he had entered ‘too many places to remember’ since he returned to San Bernardino after serving his sentence (at Preston) for previous crimes,” reported the San Bernardino County Sun, July 18, 1944. The 18-year-old burglar admitted to at least nine burglaries.