On October 10, 1890, a group of Lake County miners seeking revenge killed a woman and shot her husband. To conceal their identities, they wore sacks over their heads, earning a moniker more closely associated with vigilante groups in other states: The Whitecaps. It ended with four of the men going to San Quentin State Prison. Their violent acts helped push legislators to enact laws forbidding the vigilante practice, otherwise known as vigilance committees.

Revenge plot hatched

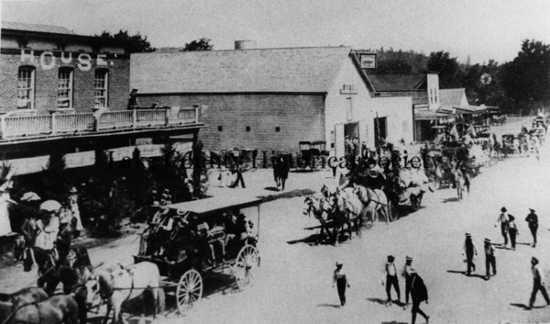

Miners in Lake County often blew-off steam at the Campers’ Retreat, a local tavern. The business was located on 62 acres near the Bradford quicksilver mine, close to Middletown.

J.W. “Stephen” Riche and his wife ran the busy gathering place for the often rowdy miners. To keep the peace, they relied on Fred Bennett, a big man who also owned interest in the Bullion Mine.

One night, after a particularly rough evening, a group of miners caused a ruckus, requiring Bennett’s intervention. After getting into a futile brawl with the bar’s burly bouncer, the miners were ordered to leave. Believing they’d been disrespected, mining foreman Cornelius E. “Charles” Blackburn set his coworkers on a course that would end in bloodshed. In early October, they met to plot revenge.

Campers’ Retreat raid

What should have been a busy Friday night for the bustling Lake County tavern was unusually quiet. A large dance was happening in town, drawing most of the locals.

Different newspapers at the time published various accounts of the circumstances surrounding that night. According to most reports, the Riches’ quiet October 10 evening was shattered around 8:30 pm by people wearing sacks over their heads as they broke into Campers’ Retreat.

Startled, Mrs. Riche ran into the room to confront the men. The first man inside had a pistol and the second had a double-barreled shotgun. Others filed in through the open door. Two men stood watch at the front door while two more men were at the rear.

The woman demanded they leave but the first man grabbed her, attempting to gag her and bind her hands. She fought back, snatching off his burlap mask. At that point, Bennett arrived, tackling one of the intruders. That’s when the shooting started.

The unmasked intruder threw the wife to the floor, firing a round into her chest. The shot, whether accidental or intentional, caused others to begin shooting. The man with the double-barreled shotgun, later identified as Bichard, fled as soon as the shooting started.

One of the raiders, still outside, shouted, “Who is doing that shooting?”

Mr. Riche ran into the room, shotgun in hand, firing at the intruders. The raiders returned fire, striking Riche in the side.

When the gun smoke cleared, the masked intruders were gone, one of them lying dead on the front porch. While Bennett rushed into town to seek help, Riche cradled his dying wife.

Police respond quickly to Lake County establishment

The sheriff and his deputies happened to be in Middletown attending the dance when Bennett rode in with his tale of the attack.

Within hours, the sheriff was on scene, his deputies surrounding the tavern while others searched McGuire’s cabin, the dead man found on the Riches’ porch.

Investigators narrowed their focus to about a dozen men, thanks to the slain wife unmasking one of the raiders. During the scuffle, Bennett recognized him as Henry Arkarro, one of the Bradford miners.

Husband dies two months later

Mr. Riche pushed for the prosecution of the Whitecap raiders, but his life was also cut short.

“Late Monday afternoon (December 29), the citizens of Middletown were thrown into a flutter of excitement over the announcement of the sudden death of Stephen Riche, who had for some time been (recovering) at the home of his friend, Heinze, a harness-maker.

“Riche had been complaining considerably during the day from pains in his head and back (so went into another room to rest).

“Mrs. Heinze heard him make unusual noises and upon (entering) his room, found that he was in great distress and apparently in a very dangerous condition. She hastened for assistance but by the time other persons had arrived, he was dead,” reported The Weekly Calistogian, December 31, 1890.

The coroner claimed the gunshot wound was not the culprit in Riche’s demise.

His death was caused by “apoplexy,” today referred to as a stroke or brain hemorrhage.

“He was of course greatly interested in the prosecution of the raiders and his death will very likely be considered a fortunate occurrence for them. With him and his wife out of the way, there remains only one person, Bennett, who was in the saloon when it was raided. He is somewhere in California but we are told that no dependence is placed upon him as a witness and that it is not probable that he will be present at the trial,” the paper reported.

1890 Lake County Whitecap raiders stand trial

“Arkarro was arrested and confessed, giving the names of those who were with him, but denied that he was in the house. Two others of the crowd, Osgood and Evans, also confessed,” newspapers reported.

Another confession came from John Francis, who did not participate in the raid but had been asked to join.

When asked to repeat their confessions at B.F. Staley’s trial, they refused. The jail in which they were held did not have enough cells to keep the men separated, giving them ample time to get their collective story straight.

On Feb. 17, 1891, the jailed conspirators “entered into a compact, had sworn to it and shaken hands (agreeing) they would not tell the story of the crime. Each bound himself to preserve an absolute silence regarding the events of the night of the 10th of October last,” reported the San Francisco Examiner, Feb. 18, 1891. “Besides this they agreed that if anyone did break the compact, all the others should go upon the witness stand and swear that that one killed Mrs. Riche.”

When put on the stand, Osgood answered each question with, “I have nothing to say.”

Prosecutor Clay Taylor pressed the defendant, even asking, “Has anybody undertaken to intimidate you.” Osgood’s response was the same, “I have nothing to say.”

The testimony of Arkarro went the same, with each answer being “I have nothing to say.”

According to Taylor, Osgood burned his mask and returned to the mine, his face still black, as each had darkened their faces around the eye holes.

Tale of plot unfolds

One of the armed men, E.A. Bichard, said he was carrying a breech-loading shotgun, supplied by Blackburn. When the shooting started, Bichard ran, later returning the gun to Blackburn, still loaded with its two cartridges.

John Francis testified he was approached by Blackburn to join the raid but thought it was a bad idea. He told his wife about the plan and she discouraged his participation.

“He told about the (Oct. 9) meeting at Bichards’ house. Staley was there as well as McGuire, the man who was killed on the Riches’ porch, Blackburn, Archer, Osgood, Cradwick, Bichard and Frank Bradford, son of the owner of the mine. Some gunny sacks were procured, and Staley, Osgood and the witness were measured for burlap suits. The sacks were cut roughly into coats. Others were fixed something like trousers. The three tried on the disguises … and the faces of all three were blackened. Blackburn and McGuire were particularly active about the disguises, and said that their own mothers would not have known them. … McGuire showed Francis the cat-o’-nine tails and said that they would give Bennett 20 lashes with it. Blackburn read a couple of letters, one to be sent to Riche and the other to Bennett,” according to Francis’ testimony.

The letter to Riche warned he would get the same treatment as Bennett if he did not “keep a better house.” Francis backed out the morning of the planned raid.

Staley first to fall in Lake County murder case

Staley’s trial drew large crowds with many believing the jury would be unable to reach a verdict since prosecutors couldn’t legally prove the defendant was at the scene of the crime.

The defense pushed their theory that Bennett planted evidence in Staley’s cabin as part of a mining rivalry since the two were partners in the Bullion mine.

It took the jury 18 hours to reach a verdict.

They finally settled on second-degree murder “with a recommendation to the Court’s mercy,” reported the San Francisco Examiner, Feb. 22, 1891.

When the verdict was read, Staley “turned to ex-Judge Hudson, his attorney, and said, ‘That’s pretty tough.'”

The damning piece of evidence was Arkarro’s sworn statement made at the initial inquest.

He said the “band gathered a few moments after the raid (and) Staley said that they had butchered the job and that they ought to go back and finish the work and then burn down the Campers’ Retreat.”

Staley’s guilty verdict paved the way for prosecutors to move forward with the other trials.

Ringleader found guilty

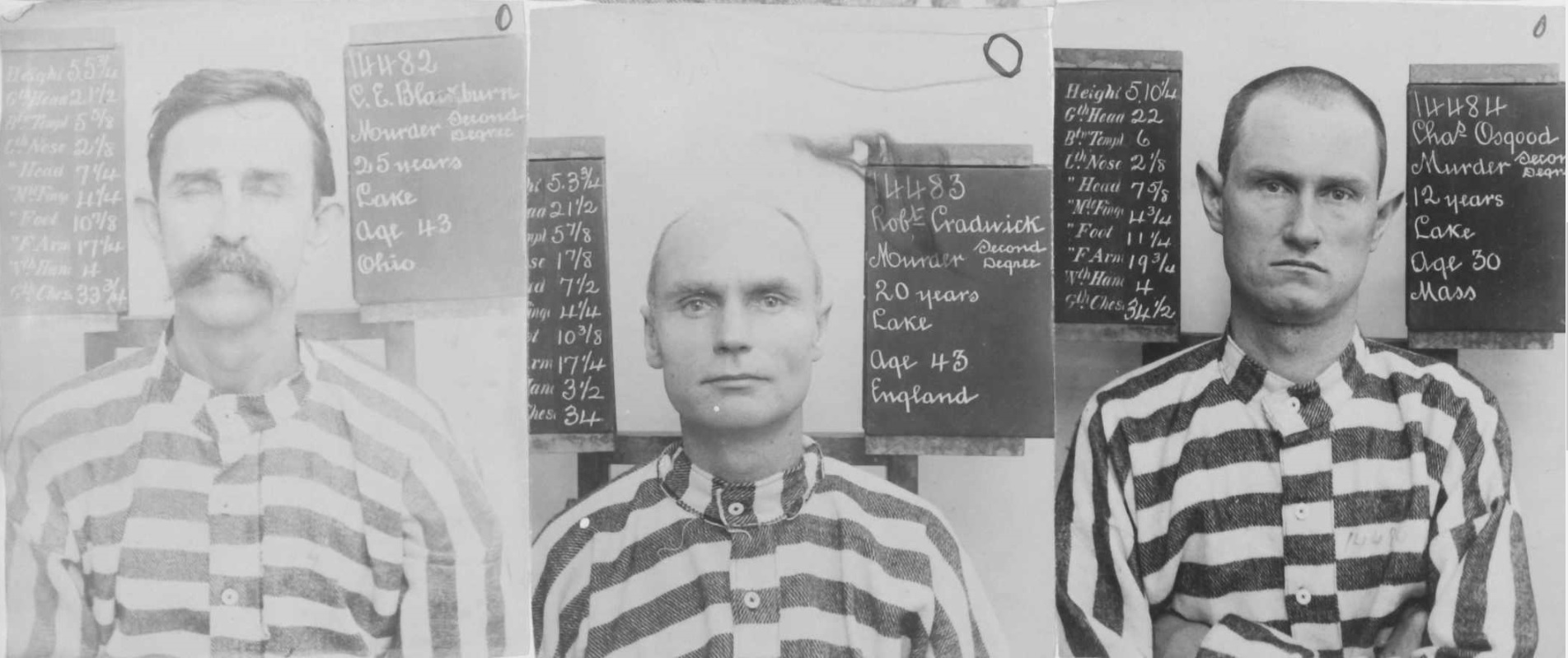

Charles Blackburn, the ringleader, was also found guilty of second-degree murder.

“The most sensational criminal case every tried in Northern California has just come to a close by the conviction of C.E. Blackburn of murder in the second degree, and by the dismissal, on motion of the District Attorney, of the indictments found against six of his accomplices. The case is known as ‘the whitecap murder case,'” reported the San Francisco Call, March 25, 1891.

“It was the old story of vengeance by a gang of miners upon a man who had incurred their dislike. … When the case opened, Francis and Osgood refused to repeat (their confessions) in the witness box, … but Arkarro, Evans, Archer and Bichard told their story frankly and under the skillful management of Clay Taylor, who was retained to assist the prosecution, a conviction of murder in the second degree was secured,” the newspaper reported.

“Then the District Attorney took up the trial of Blackburn, who was known to have been one of the leaders in the affair. His trial was long and fiercely contested. But the prosecution was able to get in evidence which satisfied 10 of the 12 jurymen that he had committed murder in the first degree. (The other two believed the crime to be) manslaughter and to reach a conclusion, the 10 had to compromise on a verdict of murder in the second degree.

“The verdict caused chaos among others caught up in the trial, with some withdrawing their guilty pleas. (For those) the prosecution dismissed the indictments on the ground that the prisoners had turned state’s evidence and secured the conviction of their leaders.”

Off to San Quentin

The four men were sent to San Quentin, sentenced on the same day.

“A final scene in the Lake county court, Thursday, has ended the most famous of local trials. The four Whitecaps found guilty of the vicious assault upon the Riches were arraigned in court and formally sentenced to San Quentin. When the Court called upon the prisoners to rise, Osgood, Cradwick Blackburn and Staley stood side by side, and they were much agitated. Staley’s face twitched nervously. Blackburn fingered one of the buttons on his coat and his face was flushed. Osgood looked down and never once raised his eyes,” reported the Sonoma Democrat, April 4, 1891.

Charles Osgood received 12 years, Robert Cradwick and B.F. Staley each received 20 years and Charles E. Blackburn was sentenced to 25 years.

Blackburn’s case popped up now and again as influential friends tried to secure a pardon on his behalf.

“The application for a pardon of C.E. Blackburn, who is serving 25 years in San Quentin, … has been rejected,” reported the San Diego Union, Jan. 16, 1893.

On Dec. 31, 1894, his sentence was commuted to 10 years by Gov. Markham.

“(Blackburn) in no way participated in the fatal results,” wrote Gov. Markham. “It is clearly demonstrated that no greater crime than that of manslaughter should have been found against him.”

He was released in September 1897 but was rearrested in 1900 on charges of horse thievery. He stole a horse and buggy a year earlier in Santa Cruz and was wanted on similar charges out of Fresno County as well as San Francisco.

As a repeat offender, Blackburn was sentenced to 10 years at Folsom State Prison.

What were the Whitecaps?

In the post Civil War era, whitecapping was prevalent in the South and Midwest, generally targeting minorities to drive them off desirable land. Under the cover of darkness, Whitecappers used whips, threats and other violent methods during their raids.

“In the outset the Whitecap realized that his mission was a violation of law and that, if detected, he would be punished. Therefore it was decided that in their criminal practices their faces should be covered with masks so that their identity would be concealed. They accordingly prepared white rags, large enough generally to successfully cover the face and head with small holes cut for the eyes, nose and mouth. … The original purpose of whitecapping was to administer punishment to (those) who lived in adultery and kept disorderly houses in the community,” wrote E.W. Crozier in the book, “White Caps,” published in 1899.

Laws were enacted across the country to help put an end to the practice. In California and other western states, Whitecap methods were used but the targets were more commonly associated with business rivalries or settling vendettas.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.