Just eight years after the Wright brothers took their historic 1903 flight in North Carolina, a California aviator took to the skies for his own record-setting flight, including two flyovers of San Quentin State Prison. This is the story of how a letter penned by incarcerated aviation enthusiasts helped plot the route flown by pioneer pilot Weldon B. Cooke.

Young aviator sets record

Dubbed the youngest of the notable flyers of his day, Cooke was a self-taught pilot. He was also the first in Northern California to be awarded a pilot’s license and only the second person in the state to hold one.

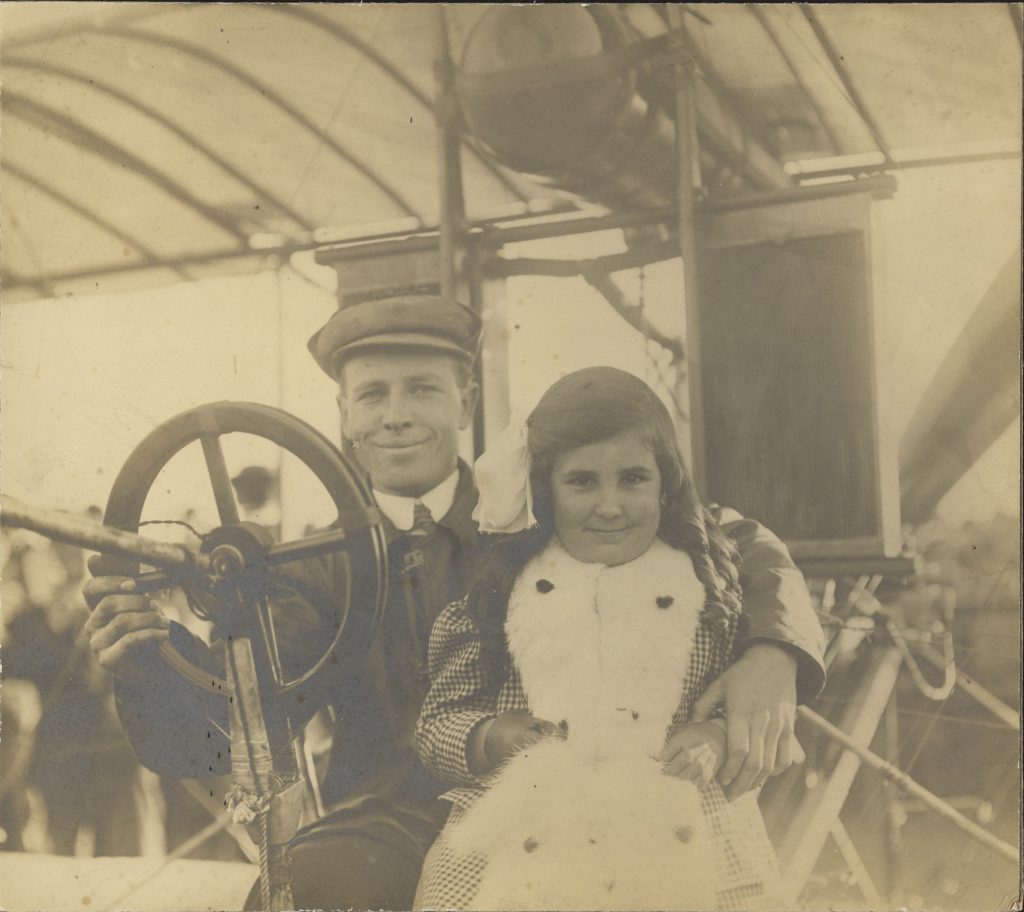

“Weldon Cooke, the daring young Oakland aviator who first came into prominence a few months ago, and since that period has startled, with great regularity, residents about the bay, will make what is really his first public appearance at the Oakland Motordome on Sunday,” reported the Oakland Tribune, Nov. 30, 1911. “(He) holds the distinction of being the youngest of the present group of prominent sky pilots.”

Cooke was 27 when he made his record-setting mark on aviation history.

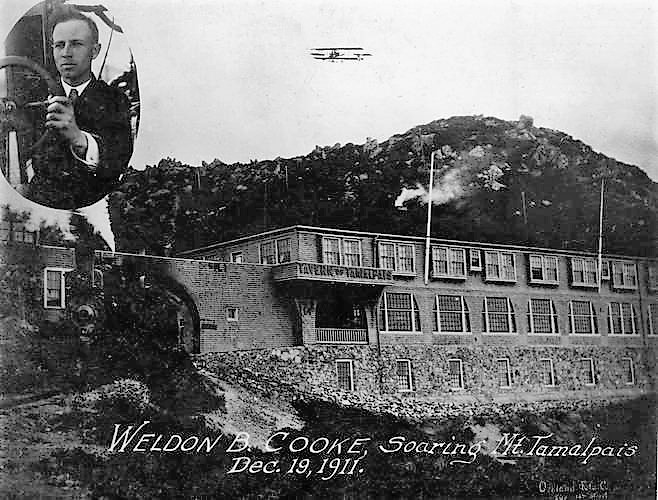

“On Dec. 19, 1911, (Weldon B. Cooke) left the Oakland Motordome, near Elmhurst, flew over Oakland, Berkeley, Richmond, across the bay, over San Quentin prison, around (Mt. Tamalpais) and landed in Mill Valley at 5:30 p.m. after being in the air one hour and 20 minutes and covering a distance of about 60 miles. His altitude from the time he was over Berkeley until he had circled around the mountain was 4,000 to 4,500 feet,” according to B.P. Lanteri’s letter published in Aero and Hydro: Aviation Weekly, Jan. 20, 1912.

While in the air, he dropped two letters, making him the first to deliver mail by airdrop in California. One letter was addressed to his brother while the other was for his college. He wasn’t the first to carry mail in a plane. Another pilot earlier that same year carried a bag of U.S. mail during a flight sanctioned by the postal service.

Historic flight over San Quentin prison

“(Cooke’s) flight took him directly over San Quentin prison, where there are men who have never seen an aeroplane,” reported the San Francisco Call.

Inmates may have been able to catch a brief glimpse of the daring aviator through the fog, but Cooke reported he couldn’t clearly see the prison.

The notion of flying over the prison was actually introduced by the inmates in a letter to organizers of the January 1911 aviation meet in San Francisco, the city’s first.

“It has been reported here that during the coming aviation meet in San Francisco a flight is to be made to San Rafael, which is three miles from here, and that the return is to be via San Quentin point. There are hundreds of men confined here who have never seen an aeroplane and some of us probably never will unless by courtesy of the aviator who will come this way,” states the letter signed The Prisoners of San Quentin. “With permission of the warden, (we ask) if it can be arranged for the machine to circle over the prison, so (we) have the opportunity to see it.”

While it took almost a year to fulfill their request, Cooke did fly over the prison. He then passed over the mountain and circled.

“(He was) so close that he could hear the whistle of the little locomotive that carries tourists up and down (the mountain),” reported the Call.

Forced to land in a field

Since he’d gotten a late start, he was forced to set down in a field in Mill Valley where he waited a few days for the weather to improve. He later said he didn’t want to ship his plane back to Oakland. He was determined to return via air.

“The hardest part of the flight was just after I left Mill Valley. The winds were strong there and the currents treacherous. The wind would sweep over the top of a mountain and bear me with awful force toward earth,” he told the Oakland Tribune, Dec. 23, 1911.

Second man in state to hold pilot’s license

When he earned his pilot’s license Jan. 13, 1912, he was recognized with a “loving cup” by Oakland’s leaders. He was the first aviator in Northern California to receive an official pilot’s license, according to news accounts.

He retired his four-cylinder plane for a more powerful six-cylinder model built by Fred J. Wiseman. Cooke also packed up and relocated to Ohio in 1912, where he established an airplane manufacturing company. His focus turned to water planes.

He also began flying in other states such as Nevada, Utah and Colorado.

“Weldon Cooke, the boy aviator, made a beautiful flight of 11 minutes duration. Ascending from the hay field, he soared out to the shores of the lake and back again. Directly after the last race, he went up again, circling over the grandstand and lagoon as swiftly as an eagle,” reported the Salt Lake Tribune, July 21, 1912.

Stunts didn’t suit him. By 1914, he criticized those performing dangerous feats in the air, saying it harmed the fledgling aviation industry.

Cooke dies in Colorado crash

During an exhibition flight in Colorado, Cooke’s career was cut short.

“Cooke, the fearless young aviator, met his death at the Pueblo State Fair in Colorado,” reported the Alturas New Era, Sept. 23, 1914. “He was 2,000 feet high when his machine struck an air pocket, turned over and (crashed), killing him instantly.”

Prior to his death, he set a Colorado state record for flying 44 miles from Colorado Springs to Pueblo.

The 30-year-old pioneer pilot was buried in the family plot in Lockeford.

What became of the plane?

In 1933, his original plane was displayed at the Oakland Municipal Airport.

“The (Black) Diamond airplane in which the late Weldon Cooke made the first flight over Mt. Tamalpais and established duration and altitude records (in) 1912, is a the gift of Mrs. Anna L. Miller and Capt. L.B. Maupin of Tudor,” reported the Oakland Tribune, Oct. 25, 1933. “Back in 1910 when the ship was constructed at Pittsburg by Miller’s former husband, the late B.P. Lanteri, and Capt. Maupin, the Oakland woman assisted by cutting and sewing the wing fabric for the craft. Since the plane was given an honorable retirement in 1912, it has been carefully preserved and, according to Capt. Maupin, is in perfect shape today.”

In 1948, the plane was acquired by the Smithsonian where it was disassembled and crated for storage. In 1998, the crates were opened. The Smithsonian then returned the plane to California.

Volunteers restored the plane, displaying it at the Hiller Aviation Museum in San Carlos.

Did you know? November is National Aviation History Month.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Office of Public and Employee Communications

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.