Historic San Quentin prison records give a glimpse into jobs lost to time.

When inmates were received at state prisons, physical characteristics were noted but they also logged the person’s occupation.

An 1887 San Quentin report reveals some forgotten jobs. Titled “Occupation of Prisoners when Received,” the report breaks down the job titles of 1,220 inmates. Inside CDCR takes a closer look at some of the jobs that no longer exist or have faded to obscurity as part of the Unlocking History series.

Amalgamator

In the 1880s, stamp mills processed ore from the mines. Mercury, also known as quicksilver, helped separate precious metals from the less desirable material. Amalgamators were part of the team, earning $3.50 per shift in some larger operations. Chief amalgamators earned $4. Workers placed the slush into cloth bags and hand-squeezed the mercury from the mixture, leaving behind balls of gold amalgam.

Blacksmith

While still a profession today, it isn’t in such high demand as it once was. When America pushed west, blacksmiths were crucial since they were able to craft tools and mining equipment. They earned $50 to $60 per month at the time. In 1887, there were 18 listed at San Quentin.

Button maker

While no details are given on the listing, button makers used a variety of materials including ivory, wood and metal. They also made buttons for uniforms, complete with emblems, such as for the military. Working alongside them were button-hole hand stitchers, who cut and sewed button holes into clothing. An 1899 San Francisco newspaper advertisement sought a “button-hole maker on custom made coats.”

Cigar maker

This must have been a popular position since 24 listed it as their occupation. Cigar makers also taught apprentices. Working alongside the cigar maker and apprentice were box makers, tobacco strippers and cigar sorters.

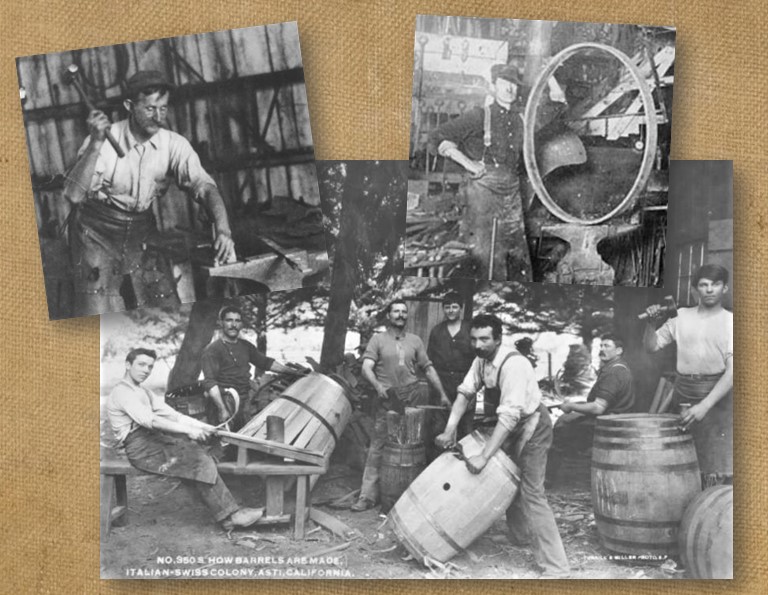

Cooper

A cooper was someone who built or repaired barrels, casks, tubs and vats using metal hoops and wood in their craft. Barrels were the preferred cargo shipping containers of their time, transporting everything from alcohol to whale oil.

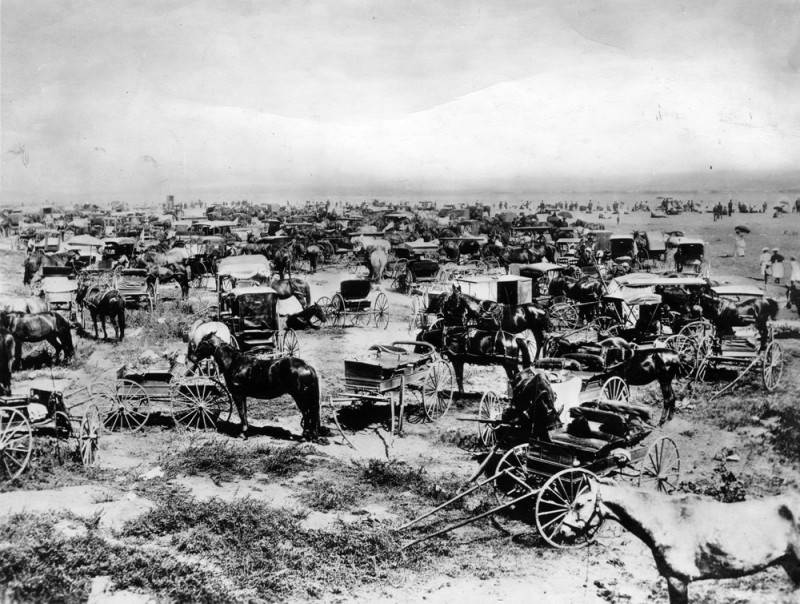

Hackman

While only one is listed in the report, the hackman was someone who drove a carriage, also known as a hackney. Passengers paid a fee for each trip, much like ride-share businesses today.

Harness maker

As the name implies, this person built harnesses, usually for horses. There were 15 incarcerated at San Quentin. According to the 1880 Harness Makers Illustrated Manual, a harness maker earned around $300 per year. “The manufacture of saddlery and harness … stands 34th in the magnitude out of the 258 specified industries tabulated in the census report of 1870. At that time there were in the U.S. 7,607 saddlery and harness establishments, (employing) 23,557, producing goods to the value of $32.7 million,” the book states. According to reports in 1891, harness makers earned $2 to $4 per day.

Ironer

While this job might appear to have something to do with forging or black-smithing, it is actually part of the laundry industry. An ironer was someone who could properly iron and press garments. Machines for pressing, called manglers, were in heavy use but their operators were paid far less than their hand-ironing counterparts. “The manglers are the great hungry machines — nests of cylinders heated with steam — into which the girls feed sheets and towels and such things at the rate of 10 or 12 a minute all day long, standing through their 12 hours,” reported the San Francisco Examiner, Aug. 19, 1900. Quality ironers, according to reports, were difficult to find. San Quentin had seven on its list. In the 1890s, hand ironers were paid $20 to $35 per month, depending on the quality of their work. “The ‘hand-ironers’ are the women who handle the pieces which cannot be done on machines,” the paper reported.

Molder

Three were incarcerated at San Quentin. They usually worked in foundries where hot metal was poured to into molds to cast various products. The Risdon Iron and Locomotive Works advertised wanting molders but cautioned, “no members of the union will be employed,” according to the San Francisco Chronicle, Jan. 26, 1870. The year before, iron molders at the company went on strike because their pay was being reduced from $4 to $3.50 per day. San Quentin had a foundry as well.

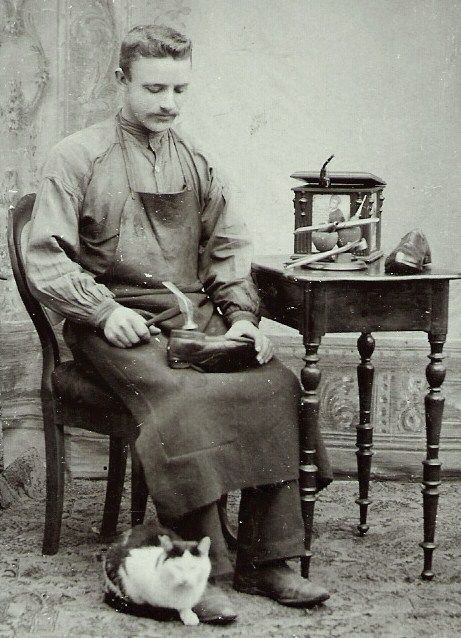

Shoemaker

Today, most shoes are created using mass production factory methods but at one time, shoes were made by hand, one pair at a time. By the late 1800s, the custom shoemaker occupation, also known as a cobbler, was beginning to fade. “There’s 10 pair of ready-made shoes worn now to one 10 years ago. Othello’s occupation’s gone — that’s me, the custom shoemaker, (a man without purpose). All that remains for me to do is patch up, repair and make new shoes out of old, while you … and all the rest of mankind do the opposite as fast as they are turned out of the big factories,” a shoemaker told the San Francisco Examiner, Dec. 19, 1886. “One can buy a pair of shoes so cheap now ready-made that it hardly pays to get old ones repaired. We are not benefited by the strides of commerce and the new inventions for making shoes. … Shoe making is an art which takes years to master. I’ve been at it these 40 years.”

Stagecoach drivers

These daring drivers crossed treacherous mountain passes, deserts and remote bandit-infested roads to get passengers, parcels and supplies where they were needed. Today’s equivalent job might be a truck driver.

Tanner

Those who tanned and finished animal hides were known as tanners. Railroads often had tanners on call to help replace belts used in the steam-powered machinery.

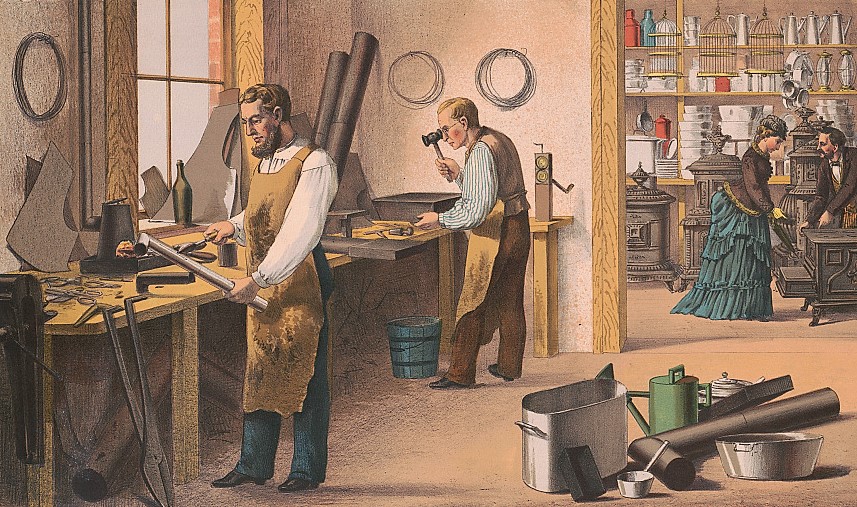

Tinsmith

Tinsmiths, also known as tinkers, created items from light metals. Their creations ranged from cookware to washbasins and metal chimney pipes.

Vaquero

There were 37 inmates who listed vaquero as their occupation. The vaquero drove cattle, particularly in the west, southwest and Mexico, but their traditions were rooted in Spain. When introduced to Hawaii in 1794, cattle flourished, eventually becoming a problem for farmers. To help manage the issue, Hawaii’s king hired vaqueros in the 1830s. They trained Hawaiians to herd cattle and ride horses. When Americans began settling the west, vaqueros served as the foundation for what would become the western cowboy.

Wheelwright

Running to the local tire store wasn’t an option at the time so wheelwrights crafted or repaired the wood-and-metal wheels for carriages, wagons and farm equipment. Wheelwrights in 1882 earned $75 per month.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.