As part of an ongoing effort to tell the forgotten stories of early prison staff, Inside CDCR takes a closer look at Henry Coleman Herrill.

The California native served as a guard at San Quentin and Folsom prisons, followed by a career as a Placer County deputy constable. Later, he was tasked with helping develop the Capitol grounds in Sacramento.

After devastating personal losses, Herrill became involved in charitable organizations and volunteered his time to improve the community. His tale spans the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

From stagecoach driver to San Quentin prison guard

Born in Auburn in 1858, Henry C. Herrill was raised in El Dorado County around Placerville. According to records supplied by his descendants, Henry and his brother George were stagecoach drivers in the 1880s, running lines in El Dorado and Placer counties. The family says Henry also used some of his earnings to invest in local mining operations.

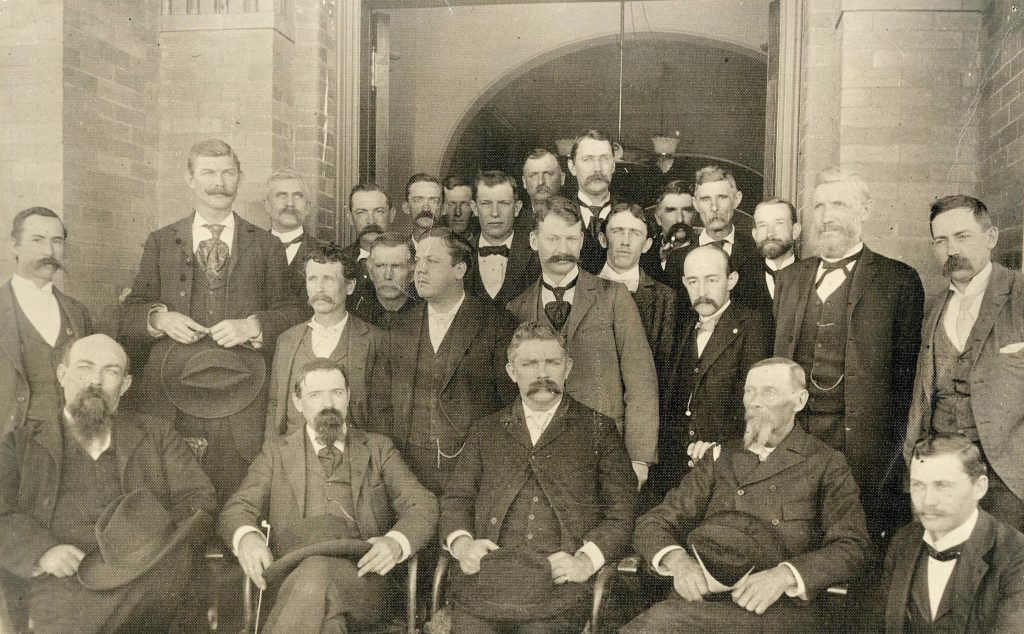

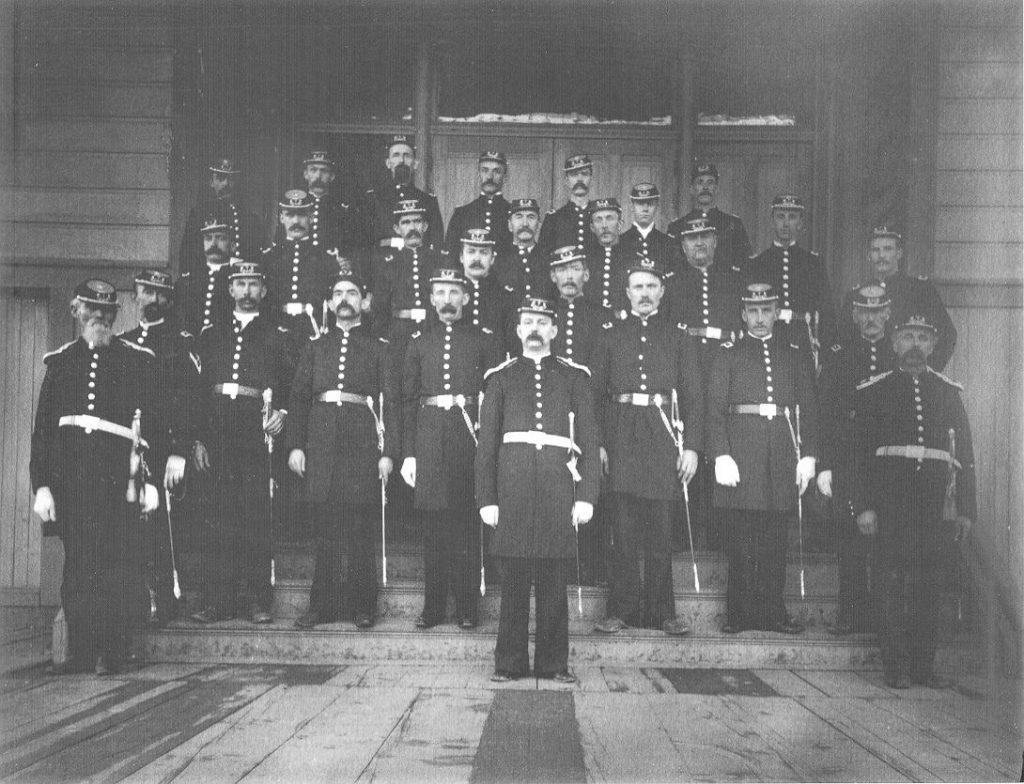

In 1891, San Quentin Warden William Hale appointed Herrill to a prison guard position.

(Editor’s note: The correctional officer job classification wasn’t created until 1944.)

Unfortunately, shortly after moving to San Quentin, the family suffered terrible losses.

Three Herrill children die in 1890s epidemic

“His friends here will be grieved to learn of his and his wife’s great bereavement in the loss of two of their little sons within the space of one week,” reported the Placer Herald, Oct. 10, 1891.

According to the newspaper, 5-year-old Guy Herrill passed away Sept. 27. On Oct. 2, they lost their 3-year-old son Henry.

Their deaths were attributed to a whooping cough epidemic.

“It is presumed the children fell a prey to (the) fatal epidemic which (has) afflicted (children across) the state,” the paper reported.

Herrill requested a transfer to Folsom State Prison so he and his wife Fannie could be closer to family.

“Henry C. Herrill, a guard at San Quentin, was in Auburn early in the week, having brought his wife up to have her visit a while with her mother at Georgetown,” reported the Placer Herald, Nov. 14, 1891.

In July 1892, they were hit again, losing their infant daughter, Verdi. All three children are buried at Mt. Tamalpais Cemetery in San Rafael.

Prison guard Herrill becomes deputy constable

In 1893, Herrill was appointed as an Auburn deputy constable post. According to the Placer County Archives, constables were essentially township police officers and not part of the sheriff’s office.

“Constable A. N. Hoffman appointed H.C. Herrill for his deputy. (He) made his first arrest at the depot while the 2 o’clock train was at the station. Mr. Herrill will make a good officer,” reported the Placer Argus, Feb. 3, 1893.

When horses were the common mode of transportation, aggravating them was considered a crime. In Nevada, for example, to protect horse traffic, camels were banned from public highways.

(Lean more about the failed Army Camel Corps experiment.)

Herrill’s horse was no exception, becoming skittish when they spotted an unusual animal.

“(On the road) to Rocklin, (Herrill) met (a man) with a trick bear. The horses became frightened and Herrill a little angry. Throwing open his coat so that his tin star was plainly visible, he (took the man to) a (judge). (The man was) found guilty and sentenced to pay $15 or go to jail. As the man had no money, the commitment was made out,” reported the Placer Herald, Feb. 25, 1893.

“(Herrill) turned to the prisoner and in his sternest voice said, ‘Come on!’ The (man) said, ‘You take good care of my bear.’ This was too much for Herrill. For the first time he realized that he had a bear on his hands, and it didn’t take him long to have the commitment cancelled,” the paper reported.

Ex-prison guard Herrill runs for office

In 1894, he ran for the Constable post, shelling out expenses totaling $7.50. He didn’t land the job but continued serving as a deputy constable.

In August 1895, he also took on the role of Placer County’s Poundmaster, the equivalent of a modern animal control officer. Back then it was less about rounding up stray pets and more about protecting stray livestock.

He often worked with law enforcement partners at the county level. One of those was 6-feet 7-inch tall Placer County Sheriff Deputy Frank “Big Dip” Depender.

“Constable Herrill and Deputy Sheriff Depender arrested a quartet of (men). Justice Wills imposed various sentences on them ranging from fifteen to thirty days. (The men) were (train hoppers),” reported the Placer Herald, May 29, 1897.

Another difficult time

Summer 1897 proved a difficult time for Herrill, beginning with a fellow law enforcement officer attempting to take his own life.

“Constable Frank Abbott created considerable excitement in Newcastle (by) attempting to commit suicide,” reported the Placer Herald, June 5, 1897. “He had been drinking heavily (and) not in his right mind when he committed the act. (An) unfortunate circumstance in connection with the affair was the arrest of Abbott by Constable Herrill on a charge of embezzlement, proffered by T.F. Hunter, of Penryn.”

On July 3, the Herrill family lost their infant daughter, Edna May.

Herrill left his post and went to work in Sacramento as a state employee.

According to the 1900 Census, Herrill was a “state official, gardener” in Sacramento. The former guard was part of a Capitol grounds’ improvement team. The job also gave him a break from law enforcement. The break didn’t last long.

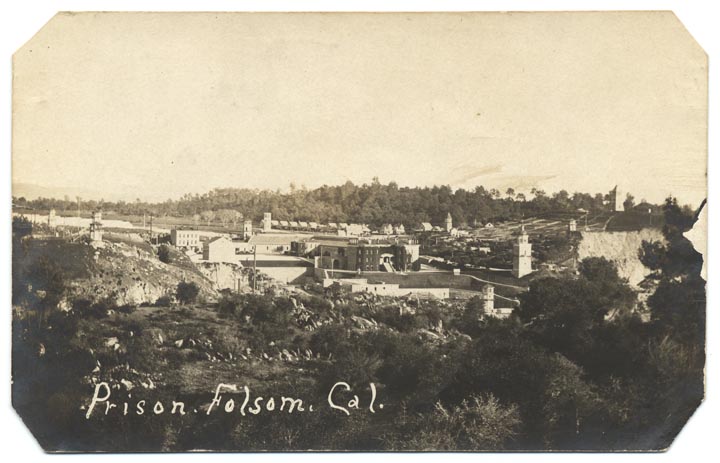

Life at Folsom Prison

In 1906, he accepted a job at Folsom State Prison, moving with his family to housing on prison grounds.

“He understood his job would be Turnkey but instead it was as a guard,” according to a 1979 letter written by his daughter, Freda.

“The farm barn was alongside of our house and to the front of us. (The barn provided) prisoners with meat and milk,” she wrote.

One day, one of Herrill’s children dressed a bull in the striped clothing worn by the incarcerated population.

“Papa almost lost his job for this,” she wrote. “The trustee convicts also lived on the farm. Mr. Woods, our neighbor, seemed like a good person and had a small house near us. He was in for murder of a man who had assaulted his sister.”

After two of his children fell ill at Represa, Herrill left his post during the summer of 1908, moving his family to Sacramento.

There he found a less stressful career as a custodian at an Oak Park school.

Becoming involved in the community

His involvement in charitable organizations started early. During the 1890s, he was a member of the Native Sons of the Golden West, acting as pallbearer at numerous funerals for members in Placer, Nevada, El Dorado and Sacramento counties.

Herrill became very active in the Knights of Pythias organization as well as the Independent Order of Odd Fellows.

“H.C. Herrill was up from Sacramento Friday night last to attend the celebration of the Knights,” reported the Placer Herald, Jan. 16, 1904.

The organization helped fund charitable activities in the region. He traveled from Sacramento to lodges within a 100-mile radius. Continuing the tradition of helping others, the modern Knights are sponsors of the Special Olympics.

Herrill’s later years

In the 1910 Census, the 52-year-old Herrill listed his occupation as gardener. He and Fannie reported six children living in the household, ranging in age from 4 to 20 years old.

By 1930, the 71-year-old Herrill was Deputy Assessor at the Sacramento County Courthouse.

Herrill passed away at 78 in October 1936.

Learn more about the organizations

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.