A tale of confidence men, swindlers, and a clairvoyant crime ring are part of the historical fabric of San Quentin.

One early 1900s case involved a network of clairvoyants, fraudulent sales of radium mining stock, and tall tales told by a smooth-talking mystic. The convoluted tale reads more like a movie script than a piece of history.

Beginning of end for clairvoyant crime ring

“Confident of acquittal, ‘Reverend’ Oscar Haas, so-called ‘(spirit) doctor,’ charged with having obtained money under false pretenses, today permitted his fate to be placed in the hands of the jury without taking the witness stand himself or calling a single witness on his behalf,” reported the Los Angeles Herald, March 9, 1915.

According to the news report, Hass “pretended to go into a trance and while in that state had permitted ‘White Eagle,’ supposed to be the spirit of a deceased Indian chief, to use his voice to induce (victims) to purchase some ranch property Haas had for sale.”

Deputy District Attorney Keetch said the victims claimed Haas, while supposedly under a trance, spoke nonsense words meant to “represent the spirit messages advising immediate purchase of the land.”

“He (induced one victim) to pay $300 per acre for land in Riverside County (claiming) the spirit of (the victim’s) deceased mother advised the purchase,” reported the Herald, March 20, 1915. “Haas had purchased the land for $20 per acre.”

Another victim said Hass claimed “spirits of the dead (informed him) real estate he owned near Banning was to become very valuable,” according to the Herald, Aug. 9, 1915. “He met his victims in a little church he (built) and witnesses said he frequently appeared to go into trances. This continued for several months (until) the district attorney (learned) about it. Haas’ arrest, conviction and sentence (soon) followed.”

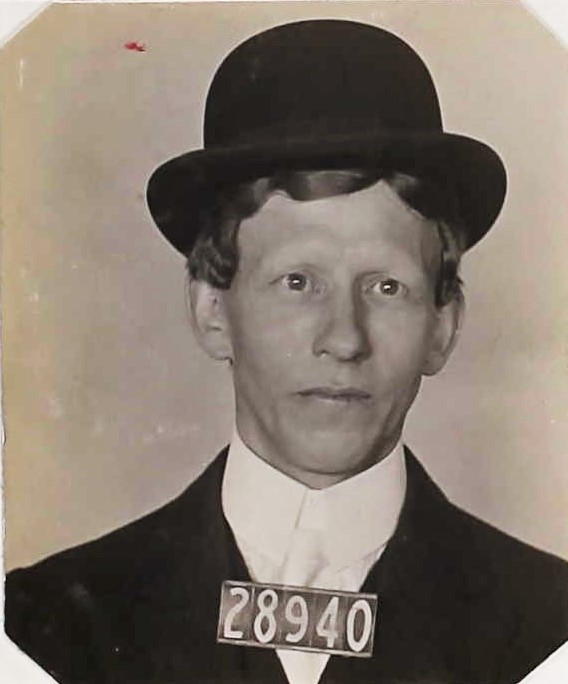

He was sentenced to two years in San Quentin State Prison, received Oct. 15, 1915. Haas, 28940, is listed as 44 years old and his occupation was “physician.” He was discharged June 15, 1917.

Detectives discover widespread clairvoyant crime ring

Investigators believed the fraudulent clairvoyant’s scam went beyond the realm of one con-artist. After four years of investigation, detectives uncovered a ring of con men using spiritualism to swindle people out of money.

“Concluding an exhaustive investigation into the alleged operations of ‘(spirit) doctors,’ mediums and clairvoyants, the county grand jury today returned three secret indictments,” reported the Herald, Jan. 30, 1919. “Bail was set at $5,000 for each person accused. It was indicated that a number of arrests probably would be made within a few hours.”

One of those named in the indictment was Carlos “Charles” de Alvandros.

For roughly 20 years, perhaps longer, he had been leading a life of crime.

Alvandros and his decades of scams

Alvandros’ con-artist career was long. In 1897, he and a female accomplice rented rooms in a hotel in New Jersey, ran a scam for a few weeks, then skipped town.

“More than 100, most of them women and some of them prominent socially, have been made the victims of a pair of swindlers who advertised themselves as clairvoyants and spirit mediums (in New Jersey),” reported the New York Sun, July 30, 1897. “The pair passed as man and wife, Charles Alvandros and Marion C. Golden. (They) came here about three weeks ago, (rented) rooms in a house and advertised their business extensively.”

The clairvoyants would convince victims to leave a valuable personal item so they could improve the readings. The victims were instructed to return in three days to pick up the object and finish their fortune-telling session.

“Wednesday afternoon was the time set for some (the victims to return). Others had appointments (for later),” the newspaper reported. “The swindlers left town suddenly on Tuesday evening.”

Manages to convince gossip columnist with his tall tales

In 1899, the fanciful tales spun by Alvandros caught the attention of a Nebraska gossip columnist. He often passed himself off as a descendant of royalty.

“I am on my way to Honolulu to see what the prospects are for the production of coffee,” he said over dinner, according to the Omaha Daily Bee, Jan. 16, 1899. “This was the explanation given in good conversational English of his presence in this city by Don Carlos de Alvandros, of Para, Brazil.”

He told the columnist he left Brazil the year prior, on his own personal steam yacht. He also bragged of already having traveled around the world twice.

“The party came in from Chicago and will go to Kansas City and thence to Denver and Salt Lake,” wrote the columnist.

“I think the American people are the best in the world, the most courteous and obliging,” Alvandros said.

Running a con in Kansas City

At least part of his story was true as a few months later, he ended up in Kansas City, rapidly separating several people from their hard-earned cash. By now, Alvandros was using the names Cecil Miller and William Benn.

“Alvandros, ‘the world’s renowned clairvoyant,’ and his (accomplice) George Duboise were taken before Judge Spitz,” reported the Kansas City Journal, Sept. 22, 1899. “(Alvandros) and his pal’s photographs now adorn the rogues’ gallery. Each was fined $5, and (Alvandros) refunded the money to each of his victims and agreed to leave (the city).”

The victims did not want to press charges.

Claims marriage after drugging a drink

In 1908, he was accused of slipping a powerful sedative in a woman’s drink in New Jersey. When she awoke the next morning, he told her they were married. Rebecca Cummings, the infuriated mother of the bamboozled bride, took matters into her own hands and shot Alvandros. The gun-toting mother, the drugged bride and her real-life husband were all arrested. Meanwhile, Alvandros claimed it must have been a conspiracy to kill him.

“Martha Hurd, whom Alvandros says he married in New York three months ago, and Edwin Hurd, said to be her husband, were held,” reported the New York Tribune, March 11, 1908.

“I first met Alvandros about a year ago, when I went to him to have my fortune told. He invited me to have a drink with him in a saloon. I remember nothing after taking the drink and I am sure I was drugged. Next morning, Alvandros said we were married,” Martha told the newspaper.

Edwin and Martha had been married for three years when Alvandros entered the picture. Cummings served a year in prison for the shooting.

Reports of a different crime then had law enforcement turning their attention to Alvandros.

“Detective Howry holds a warrant for the arrest of Alvandros on a charge of grand larceny,” reported The Sun, March 12, 1908.

According to the newspaper, Alvandros, going by the name of Imro Palma, swindled Florence Foye out of $50, worth roughly $1,700 today. After losing her job, Foye went to Alvandros hoping he could help her get reinstated.

“Alvandros said he would do this (for a) $13 fee. She paid and subsequently, she says, he induced her to buy 100 shares of mining stock he was selling, for which, she says, she paid him $50. The stock, she says, proved worthless,” the newspaper reported.

Tries to become lawyer in New York

In 1910, he attempted to gain his law license in New York but was shut down by the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court in Brooklyn.

“(The court) has refused to allow Alvandros of Tottenville, Staten Island, to practice law in this state,” reported the New York Tribune, March 6, 1910. “Alvandros, it was alleged, (deals) with fortune tellers and clairvoyants. The court committee learned, they said, that Alvandros not only had fortune tellers for his clients, but that he was one himself, under the name of Esteban Verne.”

Establishes law practice in Chicago

He pulled up stakes and reestablished his law practice in Illinois. In Chicago, his name made headlines again when Loretta Conroy accused him of swindling her out of $400.

“Miss Conroy caused a warrant to be issued for his arrest on a charge of confidence game,” reported the East Oregonian, July 20, 1912. “It was also recommended by the judge that disbarment proceedings be started against the lawyer before the Chicago Bar Association.”

The man behind the crime ring

Alvandros also faced charges for leading a ring of Chicago clairvoyants. His arrest resulted in a massive probe of police corruption and the termination of a few officers.

“Chicago police implicated in ‘white envelope’ graft fund,” reported the Sacramento Union, May 16, 1913. “(Alvandros) is said to have acted as chairman of weekly meetings held by clairvoyants where the ‘white envelope fund’ was collected for distribution to the politicians and detectives who protected their operations.”

According to reports, the con man “led a dual existence, posing as a lawyer (while also) operating as a (clairvoyant). As a lawyer he had an office downtown; as a clairvoyant he is said to have maintained three mystic parlors in which he appeared disguised to those who had met him in his capacity as an attorney. As a lawyer, he is alleged to have directed his victims to consult (his alter ego, the clairvoyant). Thus, he was able to make surprising disclosures to his victims. The less important cases were handled by assistants.”

When any of the group of mystics ran afoul of the law, Alvandros usually handled court matters.

While he and five others faced charges in Illinois, he again pulled up stakes. This time, he headed to the Golden State.

California clairvoyant ring crashes

Six years later in Los Angeles, he was up to his old tricks. Alvandros faced new charges as the leader of yet another fraud ring.

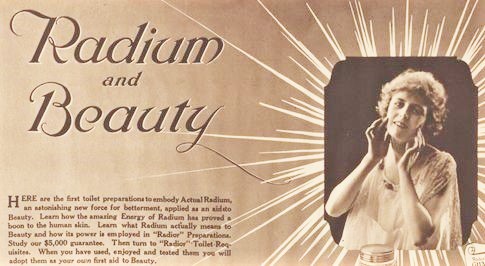

Radium mining stock also factored into the California scam since radium’s popularity was on the rise. This time, he used the aliases Professor Herold and Leon Alvandros.

Of those charged, Alvandros was the first one convicted, reported the Los Angeles Herald, April 10, 1919.

“Alvandros and (others) were arrested following the murder of Reuben Fogel, a money lender. The district attorney’s detectives uncovered what they declared was a ring of ‘(spirit) doctors’ organized as a church, but whose main purpose was to separate men and women from their savings.”

According to the newspaper, “The mediums (were) charged with having fleeced (victims by) means of ‘spirit’ messages obtained from mystic seances and other alleged tricks.” One victim said he was “fleeced of $500 and induced to buy worthless radium stock.”

Alvandros used the popularity and name recognition of radium to sell worthless stock in radium mines.

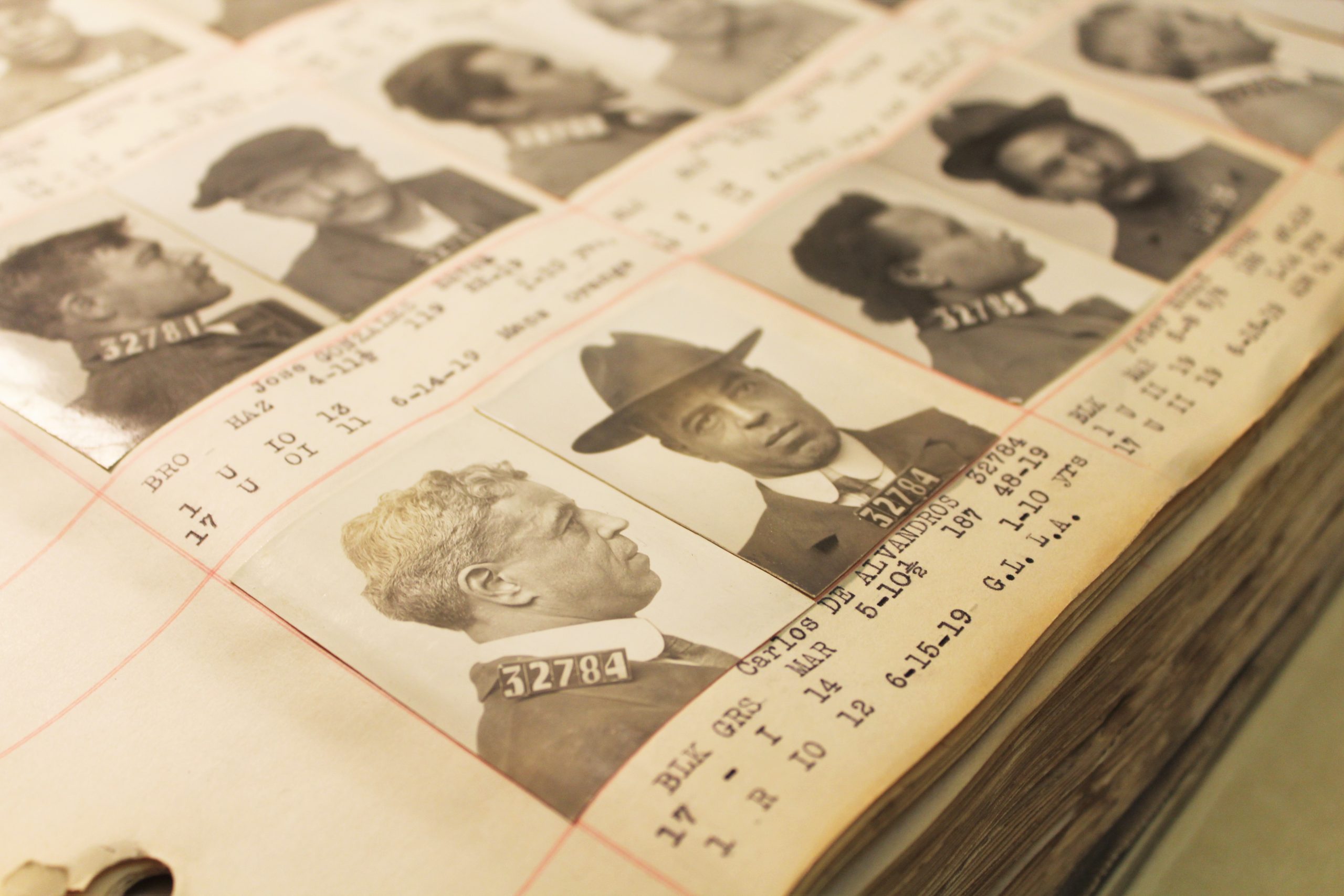

The 48-year-old Alvandros was sentenced from one to 10 years in San Quentin for grand larceny. He was received June 15, 1919, and released Jan. 15, 1923.

For Alvandros, his life of crime appears to have ended after his incarceration in San Quentin State Prison. A Brazilian-born man with the name Carlos de Alvandros turns up in a 1940 census, married and living in Seattle, but there are no further references to him as a clairvoyant or an attorney.

What is radium?

Marie Curie, the first woman to win a Nobel prize, and her husband Pierre discovered radium in 1898.

“Another extraordinary property of radium is to throw off rays not only of heat, but of light like those of the glowworm or firefly,” reported the New York Tribune, April 19, 1903. “The most puzzling property of radium is that its properties of emitting heat and light are inexhaustible.”

Madam Curie died in 1934 from radiation exposure.

Despite warnings, radium was used in health remedies, hair tonics and to paint glow-in-the-dark clock faces. Hospitals stockpiled radium to treat patients. It wasn’t until the mid-1920s when the government banned its use in health products. The glow-in-the-dark clocks were finally phased out in 1968.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Office of Public and Employee Communications

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.

Related content

Jazz music blamed for 1925 murder

In the 1920s, a teenage girl, a mother’s murder, and jazz music made headlines when they converged in San Francisco. This is the story of how a misunderstood musical genre took center stage in a high-profile California murder trial.

San Quentin and the case of the clairvoyant crime ring

A tale of confidence men, swindlers, and a clairvoyant crime ring are part of the historical fabric of San Quentin. One early 1900s case involved clairvoyants, fraudulent sales of radium mining stock, and tall tales told by a smooth-talking mystic.

California prisons have long celebrated Easter

Celebratory events marking Easter have long played a rehabilitative role in California prisons to help reentry efforts.

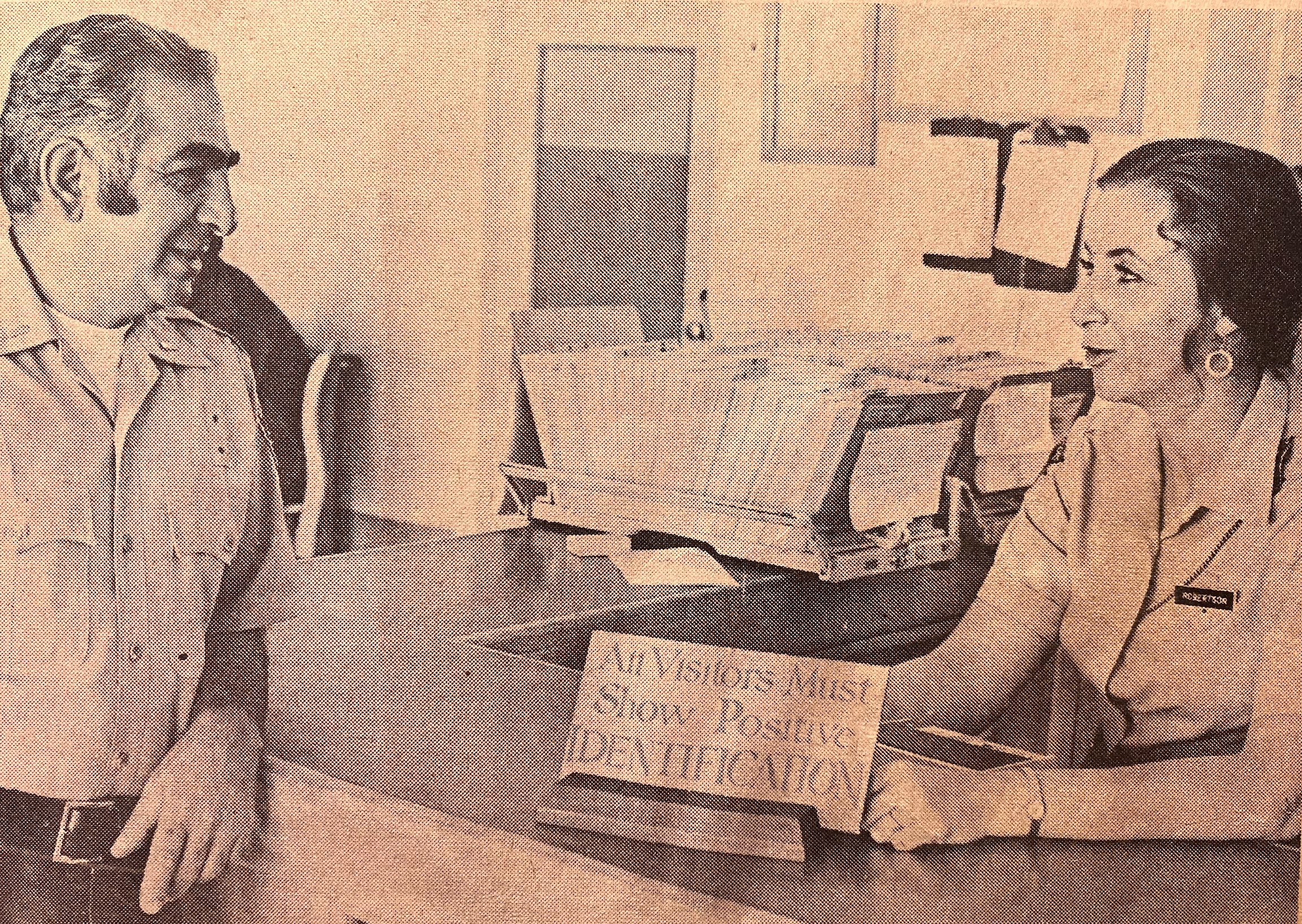

1973: DVI’s first female officer reports for duty

On June 4, 1973, Trella Robertson was hired as the first female correctional officer at Deuel Vocational Institution (DVI) in Tracy.

San Quentin evolution through the years

San Quentin Rehabilitation Center was California’s first institution to incarcerate those who’ve been convicted of breaking laws.

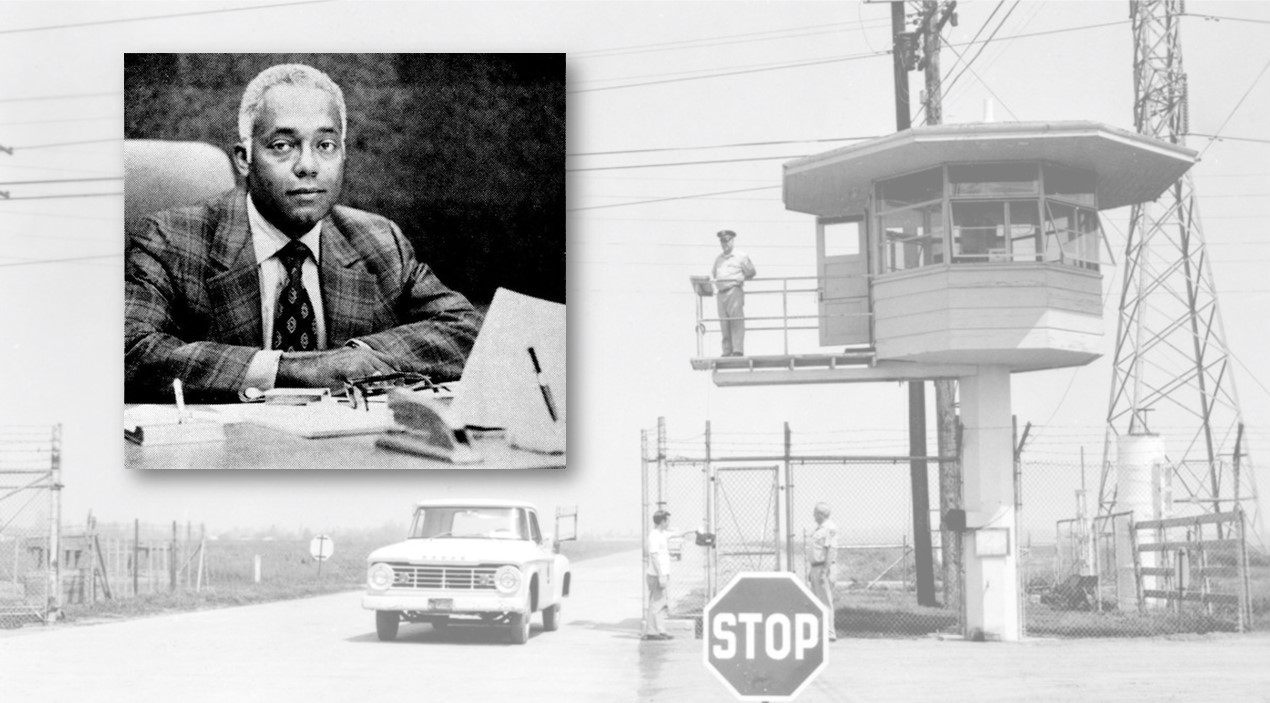

1971: Griggs was first black warden

In honor of Black History Month, Inside CDCR looks at the career of California’s first black parole administrator and prison warden: Bertram Griggs.