During a 1965 conference of Federated Women’s Clubs, the superintendent of the California Institution for Women discussed the history of women in state prisons.

According to Superintendent Iverne R. Carter, the first woman sent to the Waban prison ship was Agnes Read, a dance hall entertainer.

“In the very early days, women offenders were held in local or county jails,” Carter said. “She served one year on the (state) prison ship, (housing) both males and females convicted of felonies. The women were later moved from the ship to a small house on the shore where they were assigned to do laundry for the prison.”

Carter also described how incarcerated women were relocated as San Quentin expanded. They started on the Waban, the state prison ship, then were moved to a small house on shore, and then to other areas of the prison.

“Progressively they were moved to quarters near the wall (then) to quarters over the captain’s office with a small outdoor courtyard (where) they could get fresh air and sunshine. (Later), they were moved to the second floor of what is now Neumiller Hospital, San Quentin,” she said.

Rehabilitation was difficult in early days

Carter also listed various reasons why women didn’t have many rehabilitative programs:

- the small number (of women)

- prison practices of those days

- women housed in a men’s institution must be greatly restricted in their movements.

“There was practically no program available (except those) created by the ingenuity of the prisoners and the custodial staff,” she said. “The immediate custodial staff, of course, were women (but) all planning and making decisions was in the hands of the male staff.”

According to Carter, “the population grew from just a few women offenders until by September 1933, there were approximately 142 women housed in the San Quentin unit.”

After advocating for women’s mental health facilities, the federated clubs in 1915 began urging the state to establish an “institution for the care and rehabilitation of (women) in conflict with the law.”

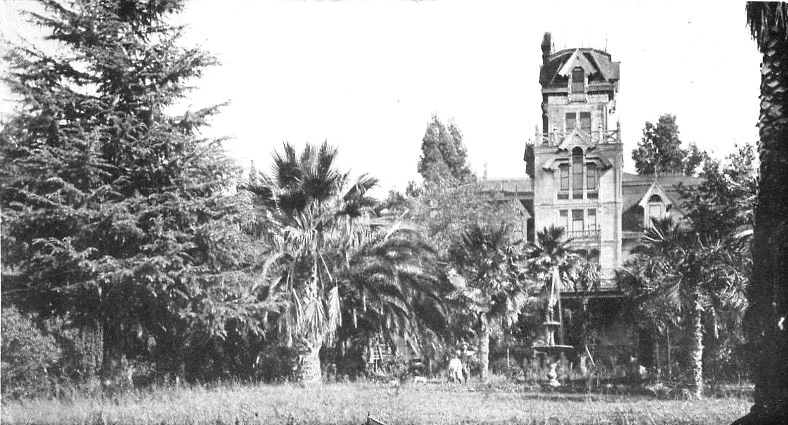

Sonoma County industrial farm for women

The first real effort came in 1922, just two years after women earned the right to vote.

“United efforts of a number of women’s organizations in the state culminated in the passing of a bill appropriating $80,000 for an industrial farm for women in Sonoma County,” she said.

The farm burned down in 1923 and wasn’t reopened.

>> Read our 2021 story on the farm.

For five more years, proponents lobbied and pushed with the help of other women’s organizations. A committee with established by Governor C.C. Young to more closely examine the issue. In the end, his committee recommended a separate institution for women.

The committee’s recommendations included many efforts considered commonplace today but were revolutionary for their time.

Reentry and rehabilitation:

- small rate of pay for incarcerated workers

- recreational, religious, and educational programs be established

- parole be granted for good behavior, determined by experts, making it probable “the woman would succeed when returned to society”

Farm plants seed for women’s prison

While the industrial farm didn’t last long, it set in motion the framework for what would become the California Institution for Women.

“The first buildings were completed in June 1932,” she said. The following year, the state legislature “enacted changes in the law, permitting the prison to open in September 1933 under the jurisdiction of the State Board of Prison Directors.”

For two more years, various women’s organizations urged the state to implement rehabilitation programs at the California Institution for Women at Tehachapi.

“They presented to the governor the rehabilitation program which included vocational, educational, and physical activities. They assisted in securing a thoroughly trained superintendent. (Under the) leadership of Florence Monahan and (later) Alma Holzschuh, the plans (were) approved by the legislature. (Then the plans) were initiated and a program gradually developed,” Carter said.

Women’s organizations continued fighting for the institution to be turned over to a female-led board. In November 1936, “the amendment (to the state constitution) was ratified by the people (and) the original Board of Trustees assumed responsibility for administration.”

>> Check out photos of California Institution for Women through the years.

War, economy impact prison for women

By the early 1940s, World War II and the Great Depression were having a serious impact on the institution. Overcrowding, difficulty recruiting staff and a lack of medical professionals were all problems in operating the institution.

Again, the women of the state petitioned for the institution to be relocated to a less remote area.

In 1944, the institution became part of the new Department of Corrections under the leadership of Richard McGee. By the early 1950s, a new institution was under construction, completed in late 1952. Prior to its completion, a severe earthquake at Tehachapi made the buildings uninhabitable.

The women stayed in tents on grounds until the new institution was ready. “Then almost 350 women were relocated to the new California Institution for Women, which was at that time constructed to house 400,” she said.

Carter also highlighted the need for improved relations between staff and the incarcerated population.

“(We) need more knowledge in the areas of human dynamics and understanding various culture patterns,” she said. “As an institution grows larger and its organization more complex, it is difficult to maintain the close professional relationships within staff and between staff and (incarcerated individuals) which are basic to the changing of behavior patterns.”

Foreshadowing modern efforts, she hinted at the concept of normalization.

“Finally, there is a continuing need for the resident in a penal institution to understand community expectations through contacts with responsible citizen groups,” she concluded.

Who is Iverne Carter?

She began working for the Federal Bureau of Prisons in 1942 as an officer at the federal reformatory at Alderson, West Virginia, then as the assistant warden at the federal prison at Terminal Island in Long Beach. Carter served as the superintendent (today known as a warden) at California Institution for Women from 1960 to 1971. After 11 years, she retired, returning to her home state of Minnesota. Carter, who passed away at 94 years old in 1998, was considered an expert in penology.

Story by Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Office of Public and Employee Communications

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.