Thanks to early prison road construction camps, incarcerated crews connected communities with parks across the state.

Much like CALFIRE/CDCR conservation camps of today, in the late 1910s and early 1920s, prison road camps were overseen by the California Highway Commission and correctional staff.

The incarcerated work crews learned about road construction, similar to how crews today learn about being a hand crew for wildland firefighting.

DID YOU KNOW?

July is

National Park & Recreation Month.

Established in 1985, the observance celebrates all parks. Learn more about the National Park and Recreation Association on their website.

Prison road camps connect communities, parks

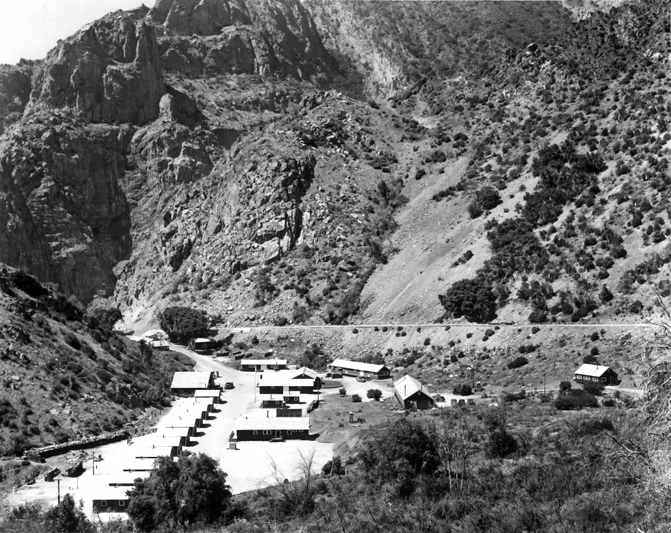

In 1923, engineers from the commission announced a new camp would be established at Briceburg “to complete the 16.7 miles of highway from (there) to El Portal.” According to the news report, “work on this final strip of road which will connect Merced with Yosemite (National Park) by highway will commence Dec. 1.”

Engineers estimated the project would take two years to complete.

“(The road) will have to be blasted from almost solid rock. The road (will be built) nearer the river and a grade of only 2 percent will be encountered by motorists. The (prison) convict camp which is now working at Shasta River will be moved to Briceburg,” reported the Sacramento Bee, Oct. 23, 1923.

Success sees growth in camps program

By 1927, more than 300 incarcerated men were assisting the highway commission in road construction.

“The last available reports (are) showing 94 men in the Redwood camp at Crescent City on the Smith River, 122 at the Bloss camp on the Yosemite highway, and 48 men at the Lake County camp on the Tahoe-Ukiah highway. Since these reports were submitted, several other men have been added to the forces in the camps,” reported the Stockton Record, June 18, 1927.

“The Legislature … specified that (the funds) be used solely for paying the men a small salary for their work on the roads. Under the convict pay system, as originated in California, the men must pay all the expenses of the camp and for their transportation to and from their work and also for the materials used, out of the wage, set at $2.10, or 40 cents below the maximum allowed by law,” the newspaper reported.

Reporter describes camps in 1920s

A newspaper described conditions and staffing levels for a road camp in 1925.

“The 16.7 miles which the state is building from Briceburg to El Portal is being carved out of the rock cliff which forms the perpendicular south bank of the Merced River. In this work only is there any suggestion of the popular (idea) of convict work. The cliff along which the seven miles of minimum 30-foot width is being constructed is so steep that in many places men are suspended with ropes while drilling blast holes or sloping off the cut,” reported the Stockton Evening Record, Aug. 1, 1925.

The paper went on to describe the general camp make-up.

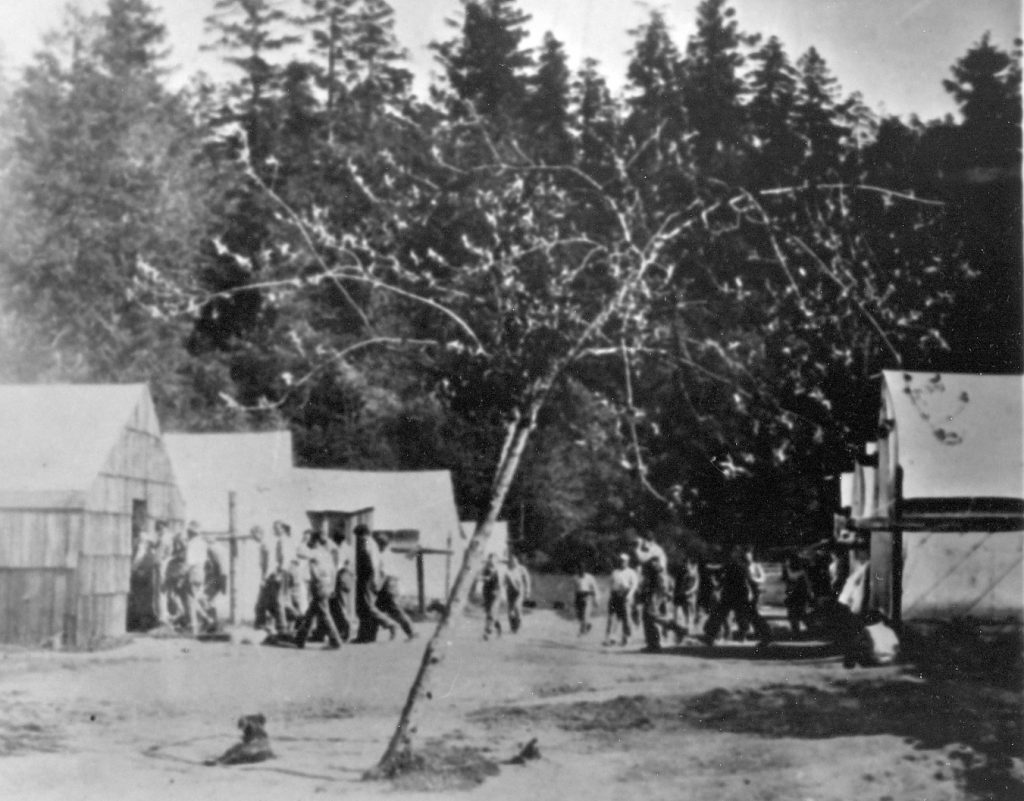

“There are 255 convicts at work. Mixed with these are 40 free men, who act as foremen, steam shovel operators and truck drivers. There are only five guards and not one of them is armed,” the paper reported.

Editor’s note: Prior to 1944, correctional officers were known as guards.

Five officers for 255 men

“Superintendent Albertson said there is no need of further guarding,” according to the newspaper. “Expressions of gloom and despair are lacking. Smiles and good nature prevail. A wave of the hand and a cheerful ‘hello’ greet the visitor.”

“Treat them right and they return the compliment,” Albertson told the reporter.

Much like today’s camps, incentives were offered.

“For every two days spent as a member of the road camp, the convict is credited with three days to his sentence. Four months in the camp and the convict has worked off six months of his sentence,” the newspaper reported.

When a fire broke out the previous year, the road crew became a firefighting hand crew.

“(During) the forest fire near the camp last year, for six days and six nights, 150 convicts were on the firefighting line. (They) had every chance in the world to escape, but every one of the 150 reported back to camp when the fight was won,” Albertson told the newspaper.

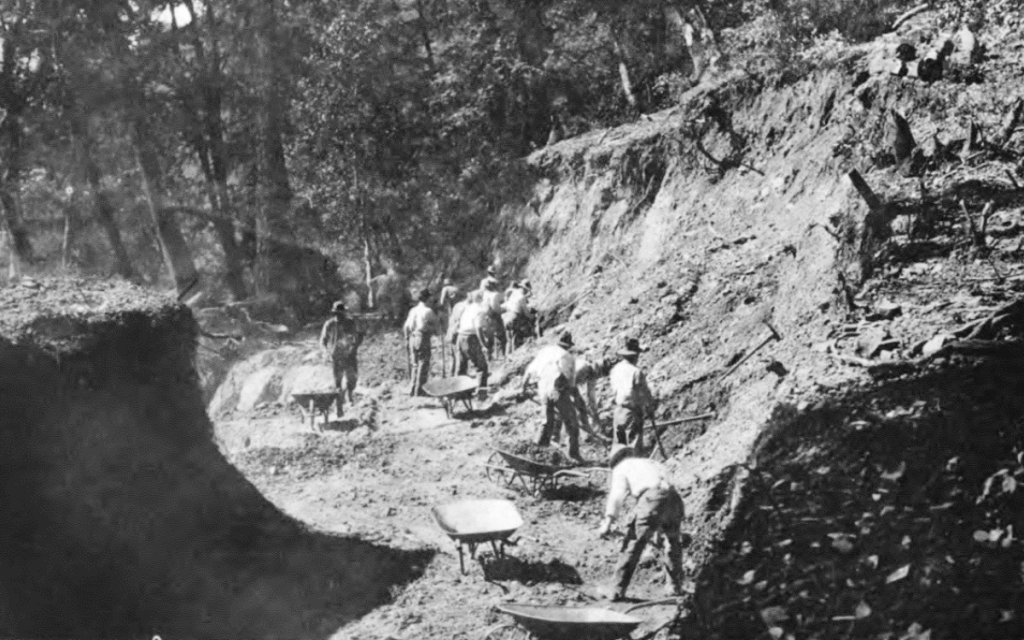

How they built the roads

“The construction work entails the use of three steam shovels and 26 trucks, purchased from the U.S. Army,” according to the 1925 news report. “Steam shovel number one follows close on the heels of the advanced powder gang. With its yard and a quarter scoop, this powerful machine does about 80 percent of the work.

“Just ahead of the shovel are the powder gang and the drillers. All day long, compressed air drills peck holes into the rock. These are burned out by small dynamite charges, and then drilled deeper.

“Muckers precede the compressed air driller and still one step ahead are the hand drillers. The advanced guard consists of brushers and trail markers. In this connection, it is interesting to note the only convict foreman is the man in charge of the brush gang,” the newspaper states.

Supporting the road crews is the commissary.

“Twelve meals are served daily, beginning with the first breakfast at 3 o’clock in the morning, when one shift gets ready for duty. There are three cooks and half a dozen convict helpers in each camp,” according to the newspaper. “The food served is better than prison food. There is plenty of it, ranging from fresh meat to milk. On Sunday, special foods are in order such as bananas and roast pork. Cakes and pies are on the daily menu.

“The camp (also) maintains an emergency hospital. This is in charge of a well-known doctor, imprisoned several years ago. The sick list is not large (while) injuries are comparatively few.”

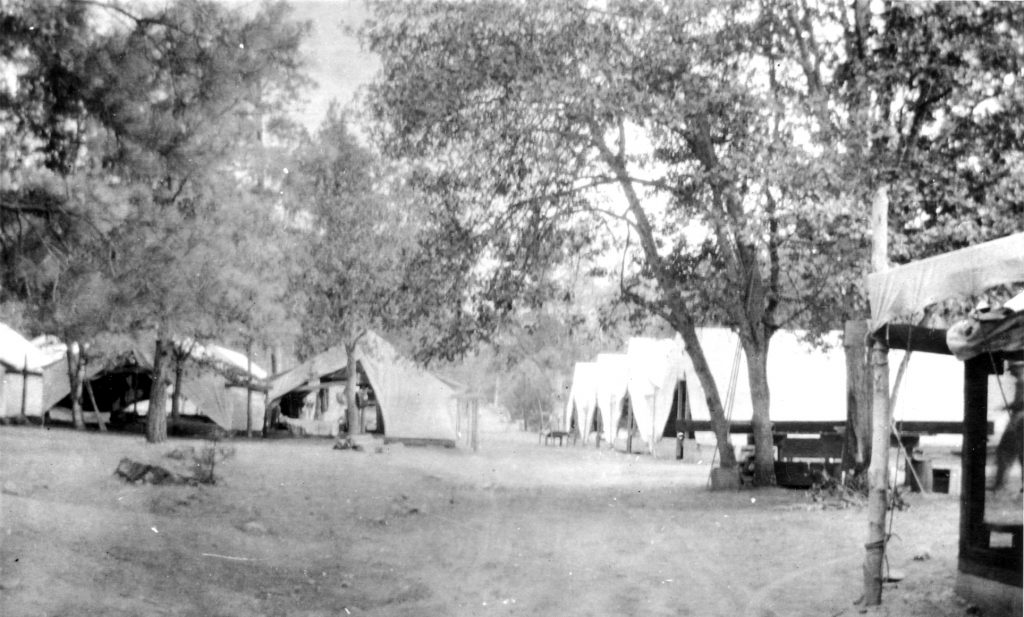

Reporter tours camp, tents

“A trip through the tents of the men is an eye opener. Everything is neatly arranged and clean. Beds are made, clothes washed, carefully folded away and shelves for personal effects lined with paper,” according to the article.

“The camp boasts a library in which there are a large number of books and magazines. A librarian has charge of issuing the books and the magazines are spread around on reading tables.”

Story by Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.