With the closure of the two previous reform schools in San Francisco and Marysville, the state established two new schools using what were considered modern approaches at the time. One school was opened in the southern part of the state and the other in the north. Part of the Unlocking History series, this installment takes a closer look at those schools and their incarcerated wards. These early efforts eventually became today’s Division of Juvenile Justice.

Southern California reform school opens

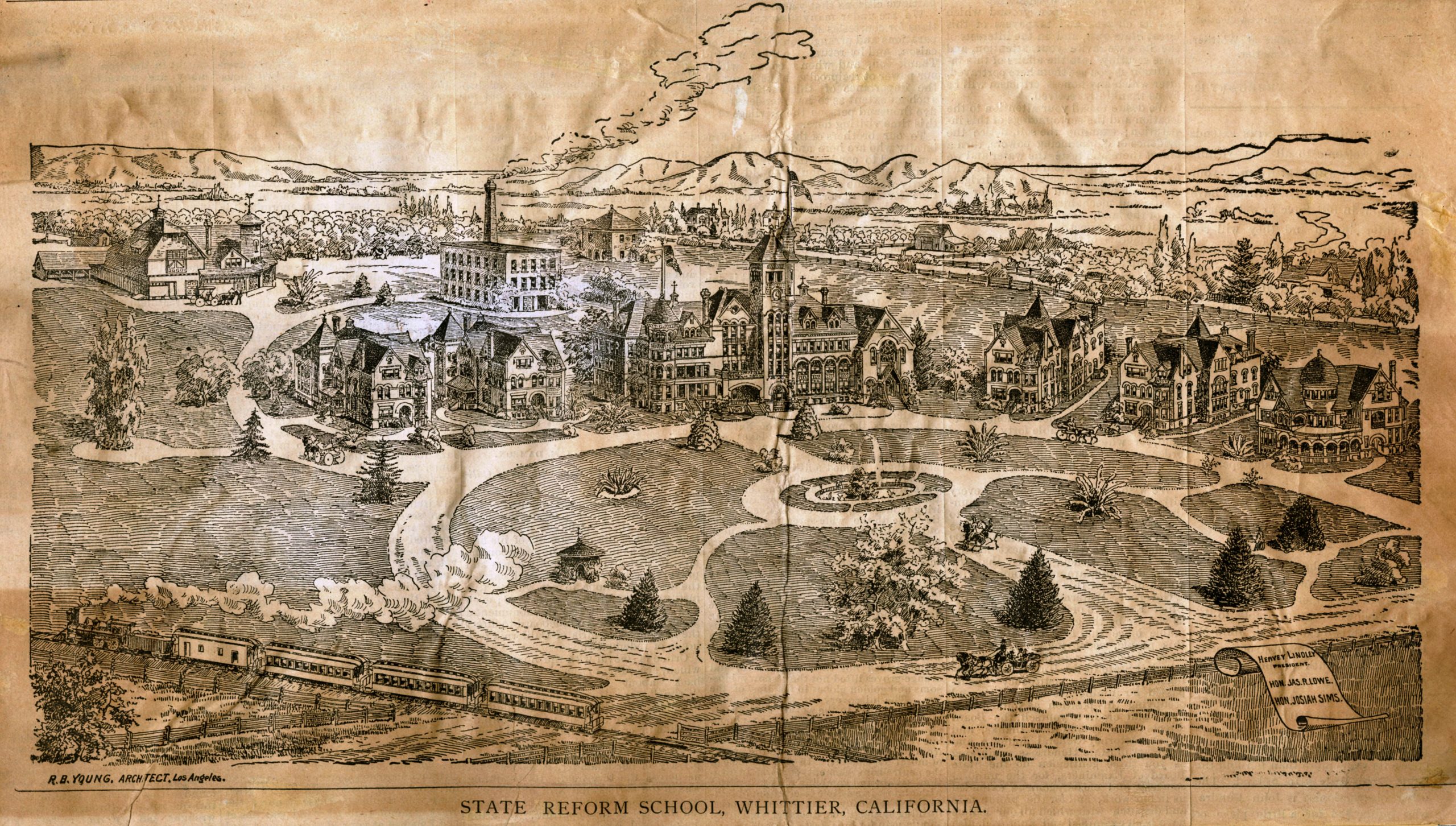

In southern California, the state established the Reform School for Juvenile Offenders in Whittier.

The school, established in 1890, was renamed the Whittier State School three years later. The school was activated in 1891.

“Dedicated by Governor R.W. Waterman on Feb. 12, 1890, the corner stone was laid before a crowd of 12,000 spectators,” according to the book, “Fred C. Nelles School: The First 100 Years.”

“The laying of this cornerstone will mark, I strongly hope, an important epoch in the future prison management of this state. May this stone, which has been so long refused by so-called prison builders, become the head of the corner of a great prison reformation,” said Secretary of State W.C. Hendricks.

In authorizing the school, the legislature provided for the “discipline, education, employment, reformation and protection of juvenile delinquents (sentenced before their sixteenth birthday),” according to the book.

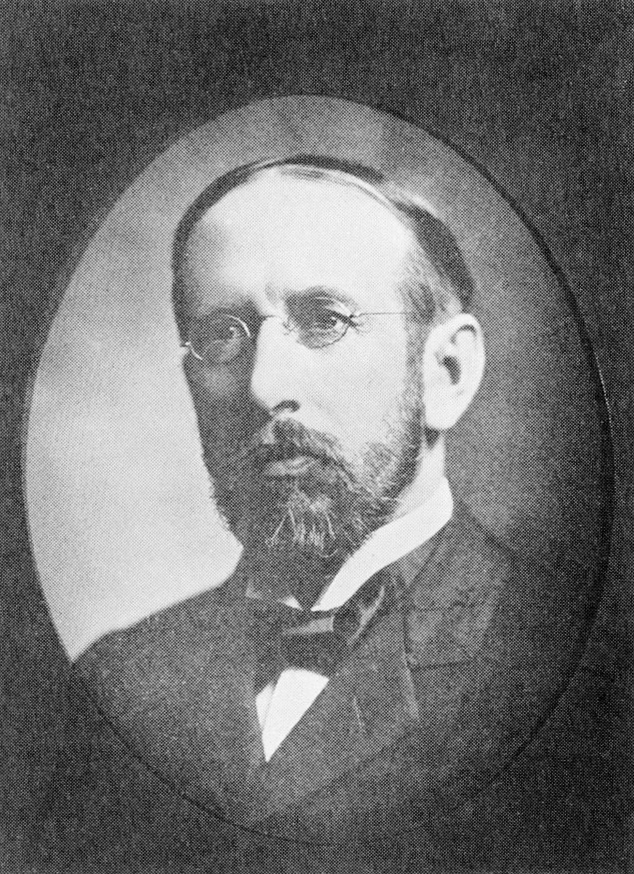

The first superintendent, appointed in 1891, was Walter Lindley, a physician and prominent citizen of Los Angeles.

“On the first of July, the Whittier Reform School will be ready for active operations,” said Walter Lindley, San Francisco Call, June 18, 1891, “and we can then accommodate 300 boys. Three teachers will be employed at the outset and it is the intention to devote from three-and-a-half to four hours a day to the instruction of the inmates. As the school fills up, the number of teachers will be increased as it is intended to provide on an average one for every 40 boys. Then, too, they will be taught trades, and in that the lineage and proclivities of the boys will be carefully studied, then they will be placed in departments best suited to their inclinations. While preparing for the work entrusted to me, I have visited the principal reform schools of the east, and will endeavor to introduce the best features of all.”

Two children sent to Whittier included 10-year-old Arthur Cervantes and 13-year-old Ralph Morse.

“Cervantes (set) fire to his parents’ home on Kearney Street, was convicted of vagrancy and will be committed to the new Whittier Reform School in Los Angeles County. (Also,) Ralph Morse … will not remain at home. (They) will enjoy the distinction of being the first offenders sent from this county to the reform school,” reported the Los Angeles Times, Aug. 24, 1891.

The boys were divided into military-style companies. Officers for each company would be selected from the boys as recognition of good behavior.

The girls’ department was overseen by Mrs. C.B. Jones, previously the superintendent of the Los Angeles school system. Other staff members who opened the facility included the boys’ housekeeper Agnes Cornell, Teacher Mrs. John A. Davis, commissary Mr. McCormack, farmer T.J. Lockhart, deputy farmer Capt. John A. Davis and gardener Louis Le Grand, well-known landscaper of Los Angeles, reported the Los Angeles Porcupine, July 4, 1891.

Capt. Davis left a job at a reformatory in Ohio so he could work at Whittier. “Davis will drill the boy’s military companies,” the paper reported.

“The steamer Queen sailed this morning for San Diego and way ports, carrying away a large number of passengers and well loaded down with freight. Among the passengers were Superintendent Kincade of the Industrial School, in charge of five small lads bound for the Whittier Reform School. They were Johnny Sweeny, Abe Zimmerman, Oscar Brenenian, Ralph Morse and Arthur Cervantes. The latter … set fire to his father’s house to enjoy the fun of seeing it burn,” reported the San Francisco Post, Sept. 3, 1891.

Governor Markham spoke openly about the public’s lack of confidence prior to opening the school.

“The entire idea, so far as many of our citizens are concerned, was an experiment, and in fact, until very lately was received with a great deal of skepticism in many quarters. The work that is being done … however, has compelled everyone who has visited the school to acknowledge its usefulness, and the superintendent is constantly receiving letters of encouragement,” the governor told the Sacramento Record-Union, in 1892.

Lindley retired from his post on Oct. 1, 1894, about a year after the death of his 34-year-old wife, but stayed involved with the institution through its board of trustees.

“Mrs. Lindley, the wife of Dr. Walter Lindley, died at Whittier last evening at 5 o’clock. Her death was caused by heart disease,” reported the Los Angeles Herald, March 11, 1893. “At the time of her death, she was the matron of the Whittier Reform School, of which Dr. Lindley is the superintendent. … Mrs. Lindley collected from friend over 1,000 volumes (of books for the library). There was no money with which to pay for teaching vocal music and she undertook that, and those who have heard the Whittier boys sing at Immanuel Church, Los Angeles, and elsewhere, can testify as to how well she did it. She said, shortly before her death, that she never expected such happiness in store for her as she had experienced in her work in this school. … Her great faith in these children and in their natural goodness, and in their future good citizenship, was as firm as the granite hills of New Hampshire, (where) she was born.”

In 1941, the place was renamed to honor Fred C. Nelles, who served as the school’s superintendent from 1912 to 1927.

The school closed its doors in 2004.

Girls’ department

The young women who were housed at Whittier were kept in a dorm “a few hundred yards away” from the boys’ areas, according to the Los Angeles Express, Dec. 31, 1891.

“The girls do not enter the building where the boys are, except for chapel exercises on Sunday afternoon. They are taught cooking, sewing and general housekeeping and go to school three hours daily,” the paper reported. “It was first supposed that it would be little more than a place of detention for the girls and that reformation would be hopeless; but the lady in charge told us that she had become very hopeful in regard to them. She said that the great aim would be to find them helpful homes and places of employment, after they left the school.”

According to California State Archives, the girls department of Whittier became independent in 1913 creating a separate California School for Girls. In 1925, it was officially renamed the Ventura School for Girls.

The girls’ school moved from Ventura to Camarillo in 1962. In 1990, Ventura School opened a camp program and instituted the department’s first female fire fighting crew.

Today, it’s known as the Ventura Youth Correctional Facility and is still in operation.

Early Whittier wards

F.K. Boitano, 12, was sentenced to two years at the Whittier Reform School, according to the San Francisco Call, July 21, 1891. According to the Sacramento Daily Union, Boitano was an unruly boy “who leaves his home in this city and remains away for weeks at a time, was found guilty of vagrancy yesterday on the testimony of his father.”

Roy Gould was 6 when he was charged with arson for igniting a hay fire in a stable in 1895. The fire spread and destroyed a grocery store. He was apparently fascinated by fire. “Frank Ecke, another small boy, testified to having seen Gould running around the streets last Saturday with a piece of burning paper in his hand,” reported the Sacramento Daily Union, Oct. 4, 1895. After his arrest, the boy was also accused of igniting a blaze in his cell. He was released due to his young age. “The judges said it would be a travesty upon justice to place so small a child on trial for arson and ordered his release,” reported the Los Angeles Herald, Oct. 10, 1895. That wasn’t the end for Roy. He took “four bits away from a companion” and was arrested. Judge Davis, who has postponed sentence several times, in the expectation the higher court would act in the matter, yesterday sentenced him to six months in the County Jail.” Two years later, “Roy Gould, the boy firebug, … was committed to (Whittier) by the Superior Court,” reported the Sacramento Daily Union, Jan. 24, 1897.

“Maude Sherer, the 16-year-old girl who broke in the residence of Mrs. Louise Burch and stole $125 in gold coin and a $50 gold watch, has been ordered sent to the Whittier Reform School, to remain until she shall reach the age of 21,” reported the San Francisco Call, Aug. 9, 1905.

“Gilbert Gardner, the 14-year-old burglar alleged to have operated in nearly every state in the Union of having stolen articles totaling $100,000 in value, was today sent to the Whittier State School to remain there until he is 21,” reported the Los Angeles Herald, Dec. 11, 1918.

Northern California reform school opens doors

Also in 1890, the state sought to purchase property in Ione for another reform school father north.

“The State Prison Directors held an informal meeting today to complete arrangements for the purchase of lands and water rights for the building of the Preston Industrial School at Ione in Amador County. … The cost of plans is as follows: cost of land, $6,900; water rights, $45,000; reservoir, $15,000; total, $66,900. The State, in its appropriation, allowed $160,000 for the purchase of land, water and the erection of buildings and maintenance of the school for the first year, thus leaving in the neighborhood of $90,000 for the buildings,” reported the Sacramento Daily Union, June 16, 1890.

“Ex-Senator Preston of Nevada, after whom the Preston School is named, spoke of the origin of the institution and the good work for which it was intended,” reported the San Francisco Call, Jan. 30, 1893. Assembly members and state senators promised they would find the money to pay to complete the necessary work.

The cornerstone held a time capsule containing the Senate Bill establishing the Preston School of Industry, the Great Seal of the State of California, numerous reports from various governmental agencies, the Constitution of California and the U.S. Constitution, a sample of silver ore from Consolidated Mine, 12 sheets of blueprints of the school, a photograph of the architect, five photos of Ione and the vicinity, and invitation and program for the laying of the cornerstone, U.S. coins, postage stamps and other various items.

The school had a difficult time through construction as money ran tight and the state opted to focus on getting Whittier completed and open first. It was delayed for nearly three years, sitting half built with a caretaker on grounds to help protect the structures from thieves or vandals. It finally opened on July 1, 1894.

The school consisted of three divisions – Academic, Military and Industrial –with each youth receiving training in all three areas.

“In the Academic course, we give to a boy of ordinary intelligence, whose stay with us is not limited, an education equal to the grammar grade in our public schools. Each boy attends school four-and-one-half hours each day, either in the forenoon or afternoon, and the other half day is spent at work, with a certain time each day for recreation,” according to the state’s 1894 Biennial Report.

“In the Military department the boys are taught daily, by competent instructors, in such branches of military training as are ordinarily used in government service, giving special emphasis to those part which secure to the cadet and erect and soldierly bearing, a neat appearance, respect for superiors, and prompt and cheerful obedience to orders.

“In the Industrial department each boy is given the opportunity to gain a knowledge of some vocation, which will be of practical assistance to him (after release), and help him to earn living wages as soon as he leaves the school.”

Of interest in this note from 1898, “Sunday, May 29 – Each cadet was given an American flag and badge containing a picture of a battleship preparatory to the celebration tomorrow.” The U.S. battleship Maine exploded in Havana Harbor in Cuba on Feb. 15 so the school was planning to honor those who lost their lives by participating in a ceremony in town.

“Monday, May 30 – This morning at 9:30 a.m. the three companies of cadets formed in front of the administration building. A large float representing the battleship Maine – most artistically gotten up by Mr. Tharsing – drawn by four horses headed the procession; then came the school band followed by the cadets, under command of Major Blair, who marched to Ione and took part in the exercises of Decoration Day. The school contingent was the main feature of the day’s proceedings.”

Grub at Preston

The average meal served at Preston in 1904 included:

Breakfast

- mush

- hotcakes

- bread and butter

- coffee and milk for breakfast

Lunch

- milk toast

- roast beef

- cabbage

- bread

- milk

Dinner

- Stewed beans

- bread and butter

- pie

- tea

Most of the food consumed at the school was produced on the school’s farm.

In 1906, the school updated to “a complete telephone system over the extensive grounds and buildings, with central switchboard.” By 1908, there were 348 youth offenders incarcerated at Preston.

In 1945, Superintendent O.H. Close retired after serving 25 years in the position. He retired because he was appointed to the newly created California Youth Authority.

Preston closed its doors in 2011.

Early Preston wards

Willie Banning “was sentenced to (Preston) for eight years” while “two boys, named Ed Douty and Harry Quinn, (were) each sentenced to a term of three years in the Preston School of Industry,” reported the Sacramento Daily Union, March 20, 1895.

Lewis Parker, 16, “is being taken from San Diego to … Preston (and) was placed in the city jail for a few hours yesterday by the officer in charge. Parker has a bad record for a boy of his years. He ran away from home and went to South America, working his way on board a ship. Before leaving San Diego, he had committed a number of thefts and on his return was apprehended and arrested. He will now spend his minority in the reformatory,” reported the Los Angeles Herald, May 1, 1897.

Joseph Lasturer was sentenced to Ione and Whittier reform schools but proved to be “totally incorrigible” after he ran away from both institutions. He was sentenced to serve four years at Folsom prison, according to the Los Angeles Herald, Dec. 14, 1897.

Louis Baker, 17, was “sentenced to three years at the State School at Ione. The lad has, during his six-month career as a burglar, gotten together a rare collection of dynamos, typewriters, cameras, guns and bicycles,” reported the Sacramento Daily Union, Jan. 23, 1898.

Wallace Williams, a burglar, pleaded guilty to a reduced charge of “petty larceny” in 1899 so he could be sentenced to Preston. He was 15 at the time.

Daniel Measure, 15, “was arrested in the store of Adams-Booth Co. on Tuesday night … and charged with burglary. He was loaded with groceries which he had packed up to carry away. It is a regrettable affair, as his parents are respectable, but he seems to be incorrigible, and yesterday the proper papers were prepared in the Superior Court for sending him to the Industrial School at Ione.”

Robert Barry, 16, “helped his brother Frank loot a sleeping car of its brass work,” according to the Sacramento Daily Union, Dec. 13, 1899. “He will make his home at the Ione School until he becomes of age – provided he doesn’t escape.”

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.