Institutions for young offenders sparked the need for more oversight, resulting in a new agency: the California Youth Authority.

While females were just breaking through barriers to become correctional officers in male prisons, a woman headed the youth authority in 1976.

It’s believed she was the first woman in the nation to lead a statewide prison system. This is the fourth and final part in the series.

California Youth Authority created

In 1941, the state legislature created the California Youth Authority (CYA) as a “completely new method of dealing with youthful criminals,” according to the Healdsburg Tribune, Aug. 13, 1943.

The state gave CYA a budget of around $200,000, of which $60,000 was meant to pay the three board members’ salaries.

“However, fairly wide latitude of action remains with the authority (for) administering Preston and Whittier schools for boys and the Ventura school for girls,” reported the newspaper.

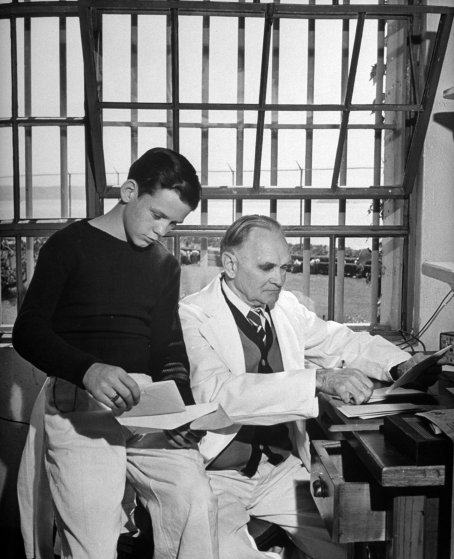

First CYA director: Karl Holton

Karl Holton served as the first director of the CYA. In June 1943, military service members stationed in the Los Angeles area clashed with Mexican-American youth. The altercations became known as the Zoot Suit Riots. Holton continued serving in his role until the early 1950s.

Second CYA director: Heman G. Stark

“The appointment of Heman G. Stark, Los Angeles, as member and director of the California Youth Authority was announced by Gov. Earl Warren yesterday. Stark, for nine years chief of the division of field services of the Youth Authority, will succeed Karl Holton, also of Los Angeles, effective Sept. 1,” reported the Madera Tribune, Aug. 13, 1952.

Stark was the longest-serving director of the agency, holding the post until 1968.

By 1958, the state had spent $9 million over a decade to help rehabilitate young offenders.

“The California Youth Authority reported recently that the state has paid $9,077, 878 to its counties during the 10 years ending Dec. 31, 1958, to encourage county camps for the rehabilitation of delinquent youths. During the same period, a total of 15 counties participated in the program and spent $22,712,891 of their own funds,” reported UPI, Nov. 16, 1959.

Learning from other states

In 1960, Stark traveled to New York City “to study the impact on young people of crime, violence and horror as depicted in the movies and television,” according to UPI, June 6, 1960. “The director will join a 15-member committee, supported by the Ford Foundation and the National Institute on Crime and Delinquency, to study the problem.”

A 1960 report published by CYA showed how 9,812 juveniles spent their time. Of those, 3,356 worked full time while 628 worked part time. There were 1,357 parolees in school and 404 absconded. Only 1,626 of the juveniles were female.

Ending up in a state youth prison

Early statistics showed how many youth were referred to the state juvenile justice system.

“Out of 2,351,000 youth between the ages of 10 and 17 in California, an estimated 3,781 will be referred by the juvenile courts to the Youth Authority for the first time for juvenile delinquency this year, according to state reports. Juvenile arrests in 1961 totaled 8,487, but not all of these were ultimately referred to the Youth Authority,” reported UPI, Dec. 19, 1962.

A 1963 UPI article on young offenders reported on a report profiling the typical incarcerated youth.

“The typical Juvenile delinquent goes to church, associates with the ‘wrong crowd,’ dislikes school and comes from an unstable home. This was the ‘profile’ of an average delinquent as published Tuesday by the California Youth Authority,” reported the Madera Tribune, Nov. 20, 1963. “Based on statistics for 1962, 46 percent of California’s male delinquents attended church ‘occasionally’ during the two years before they were committed to a Youth Authority institution. Twenty-six percent attended ‘often’ and 25 percent did not attend at all. And if the boy did not dislike school outright, he at least was ‘indifferent’ to it. Also he had ‘many delinquent contacts before being committed.”

About a third of youthful offenders were incarcerated due to being involved in violent crimes, according to a 1975 report.

“Nearly 34 percent of the youthful offenders committed to the California Youth Authority, or about 900, in 1974 had been involved in crimes of violence,” the Desert Sun reported, Feb. 11, 1975.

Rehabilitation is goal

Rehabilitation of offenders, thus promoting long-term community safety, has been the goal of the state’s correctional system since it was created. Throughout the decades, correctional leaders have reminded staff and the public of its mission.

Shortly after taking office in 1968, CYA Director Alan Breed wrote, “The prevention of delinquency, the strengthening of county probation programs, and the rehabilitation of committed youths are the major goals to which the Youth Authority is committed. Experience of many years has shown very clearly there is little to be gained from a simple program of institutionalizing and finally paroling a juvenile offender. Institutionalization is expensive, and by itself accomplishes little toward what we see as our major objective – the restoration of a youthful offender as a productive member of society.”

Eight years later, prior to his retirement, he wrote in the 1976 Youth Authority Quarterly.

“My years with the Department have taught me a number of things, not the least of which is the difference in the public’s perception of the Youth Authority and the reality of what actually takes place,” he wrote. “The public’s view is a simple one – that the Youth Authority is primarily an agency which punishes, or at least should punish, youthful offenders for their misdeeds. The Youth Authority’s real goal is not to punish offenders (because) the concept of retributive punishment is ruled out by the original Youth Authority Act. That Act requires us to provide programs of treatment and rehabilitation.”

His successor carried on this concept.

First female director: Pearl West

The first female director, Pearl West, was appointed in 1976 to replace retiring Director Breed. She was no stranger to leading the way.

“West may be best known as the first woman to be named Stocktonian of the Year and director of the California Youth Authority. In that latter role, she also is believed to have been the first woman in the nation to lead a statewide prison system,” reported the Stockton Record, June 13, 2017.

“West additionally served as chair of the state’s Youth Authority Board, coordinator of Community Education at San Joaquin Delta College, president of the Lincoln Unified School District Board of Trustees and countless other local, statewide and national organizations. More often than not, she held a leadership role.”

According to West’s family, she spent years volunteering with the county’s juvenile programs before getting involved at the state level.

“Even as punishment is imposed in the form of incarceration, the Youth Authority’s responsibility is to prepare (them to) return to the community. The average young offender committed to the state shows (most) are greatly disadvantaged and need many kinds of help,” she wrote in the Pepperdine Law Review, 1979.

Positive rehabilitation stories lost in media

According to West, because rehabilitation doesn’t make headlines, the public focuses on the stories they know.

“Success is difficult for the public to appreciate when press attention is riveted on the failures (such as) those who commit new and sometimes serious crimes when they are paroled. Although there is a success to match every failure, the successes rarely come to the attention of the public. Productive, law-abiding behavior is considered the norm and unworthy of space in the news columns. Most of our successful former wards would just as soon have it that way. Their (criminal) careers behind them, they may justifiably want to concentrate on looking ahead,” she wrote in 1979.

West went on to highlight success stories.

“There is the ward from Preston who became a well-known disc jockey in San Francisco. Another, who was incarcerated at a conservation camp, has become a medical doctor. Several years ago, a former ward plunged into a burning car. (The former ward) saved the lives of a woman and her small children. There is a cameraman on a certain TV station, the owner of a car wash and an ophthalmologist. There is an element of goodness in most, if not all, of our wards. It is this positive element we must nurture and tap (to benefit) the ward and society as a whole. If that is rehabilitation, so be it.”

West died June 3, 2017, at age 94.

First California Youth Authority ward: Barney Lee

Known as “YA 1,” the first juvenile sentenced to the newly created California Youth Authority was 14-year-old Barney Lee. Originally sentenced to San Quentin, Lee was convicted of killing his uncle over an argument regarding chores.

“Penologists oiled the wheels of justice today (attempting) to free 14-year-old Barney Lee from San Quentin prison,” reported the United Press, June 22, 1942. “Barney, who doesn’t look 12 years old, is under a life sentence for second-degree murder. He shot and killed his uncle, Nickoli Payne, 36, at their ranch in the Monterey County mountains, (after being scolded).”

He was sent to the Preston School of Industry at Ione on Aug. 17, 1942.

“The newly created California Youth Authority’s first charge, young Lee, made the trip (to Ione) by automobile. (He was accompanied by) Preston transportation officer J.E. Cohn, teacher John Palmer, and Harold Slane, one of the authority’s three members,” reported the Associated Press, Aug. 17, 1942. “As the car entered the Preston grounds and passed between the shaded rows of buildings, he said, ‘Oh, this looks just like a university, doesn’t it? Do you suppose when I gain a little more weight, I can play football?’”

Lee then went on to Whittier school and was eventually paroled. In 1952, he was released from parole. It is said he returned to Preston school to visit assistant superintendent Tom Montgomery in the late 1950s. He was married and had a family.

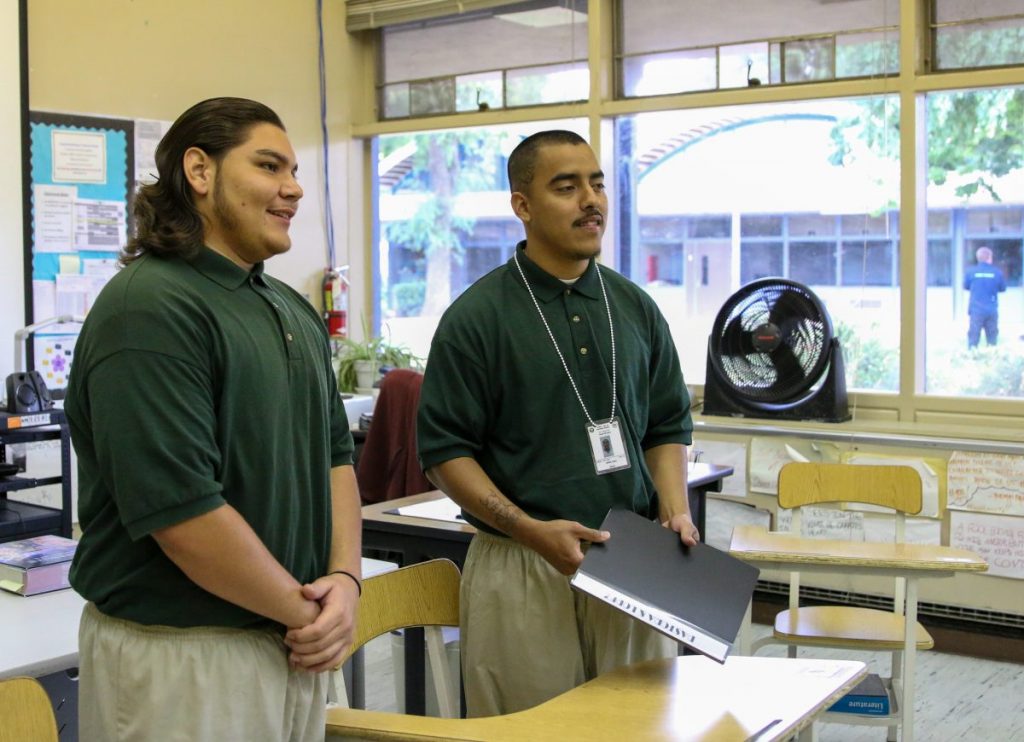

DJJ today

(Update: DJJ ceased operations as of June 30, 2023.)

In a reorganization of California corrections agencies, the CYA became the Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) in 2005.

“Today’s DJJ provides academic and vocational education, treatment programs that address violent and criminogenic behavior, sex offender behavior, and substance abuse and mental health problems, and medical care, while maintaining a safe and secure environment conducive to learning. Treatment is guided by a series of plans supervised by the Alameda Superior Court, as a settlement agreement in a lawsuit known as Farrell,” according to DJJ’s website. “Youth are assigned living units based on their age, gender, risk of institutional violence and their specialized treatment needs. The population in each living unit is limited and staffing levels ensure that each youth receives effective attention and rehabilitative programming.”

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Office of Public and Employee Communications

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.