Early reentry effort was public, private partnership

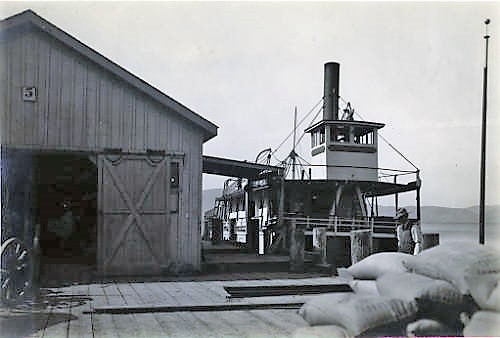

Rehabilitation and reentry have long been goals for corrections, even if it meant employment on a ship ferrying supplies to San Quentin. After the state moved on from maintaining its own small fleet of ships, sea-going vessels still played a role in rehabilitation.

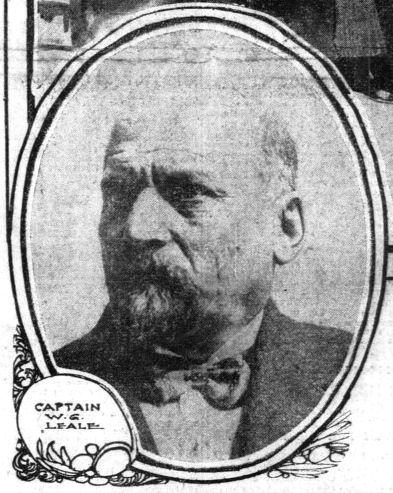

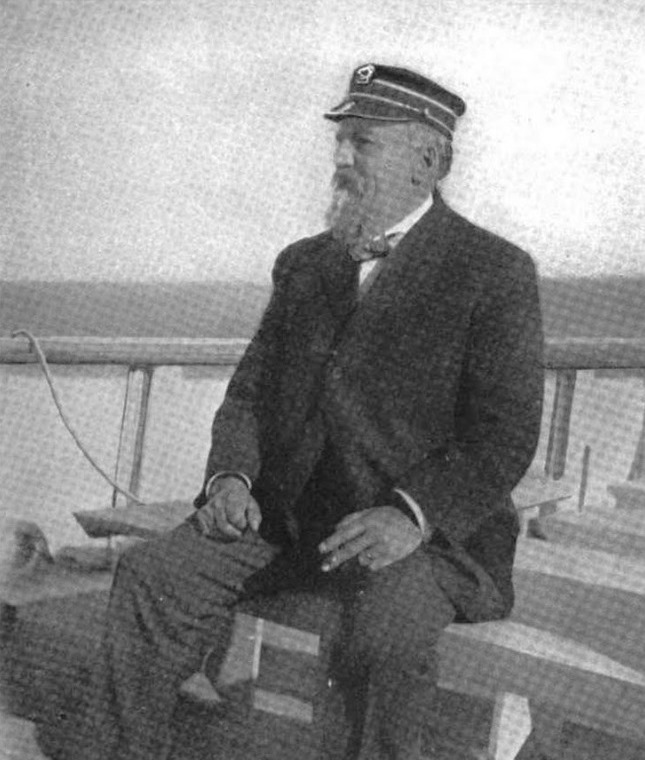

Those who learned job skills at the prison often had difficulty landing employment post-release. Luckily, they found an eager ally in a grizzled sea captain. He had delivered supplies as well as prisoners to San Quentin for decades – usually staffing his ship with former offenders.

“Under command of Captain William Leale, the Caroline plied between San Francisco and San Quentin for years, carrying (supplies to) the prison,” reported The American Marine Engineer, March 1918. “Leale, until his retirement when he tied up the Caroline annually, put the little bay steamer into the dry dock for overhauling and painting, and then he gave an outing to his newspaper friends of the bay cities.”

Retired Associate Warden Richard “Dick” Nelson said Leale was known for his involvement in the community.

“Captain Leale around the 4th of July each year would bring his boat over to San Quentin, load up the families of the prison employees, and take them on a day long tour of the bay and a picnic lunch Angel Island,” he said.

Formerly incarcerated find jobs, reentry help, thanks to ship captain

His passengers had no idea the crew had once done time in the state prison.

“Her crew for the most part was composed of ex-convicts, but none knew this except her kind-hearted captain and owner, Captain Leale, who believed that every man had a regaining quality when put upon his honor. For many years, Leale made it a point to employ none but discharged convicts from San Quentin as members of the crew of the Caroline,” according to the Marine Engineer article.

“The Caroline was always well supplied with good food and her skipper gave good advice to his crew. More than that, he sent them out into the world with a new lease of life.”

Leale had also transported incarcerated men and women for years as part of a contract with the state prison.

Early artistic rehabilitation effort finds support from captain

In 1911, Leale volunteered to shuttle actors, props and equipment, as well as some audience members, back and forth to the prison for its first-ever stage production by an outside theatrical company.

The captain had a well-earned reputation for giving formerly incarcerated men a chance. According to a November 1912 Sunset Magazine article, the captain was 68 years old.

“It was in the midst of the cantaloupe season, and the market in San Francisco was glutted,” the magazine reported. “On Jackson-street wharf, 200 crates of cantaloupe were piled and since there was no market for them, they could not be sold. Since they were perishable goods, they could not be returned to the farmer who shipped them. Since the consignee refused to accept them and move them off the wharf, the (wharf chief) ordered the crates be dumped overboard.”

Seeing needless waste, Leale confronted them.

“He demanded to know why in blue blazes 200 crates of perfectly good cantaloupe should be consigned to the fishes when 1,800 poor devils up in the penitentiary at San Quentin were ready and willing to eat them,” the magazine reported.

“I can haul the Caroline alongside, and I’ll relieve you of those crates of cantaloupe in about two shakes of a lamb’s tail,” Leale told them.

According to the story, “Leale’s specialty is the (chronically impoverished). It’s a habit. He can’t help it. That’s his nature and it’s the marvel of the San Francisco waterfront how the earnings of the Caroline stand the strain of this salt water philanthropist.”

Captain Leale helped those in need

The captain was very familiar with the prison and its inmates.

“The Caroline has been carrying miscellaneous freight to San Quentin for 30 years,” the magazine reported. “The most hardened criminal has a smile and a good word for the skipper when the old Caroline (visits the) prison dock.”

Leale treated the inmates as men with names rather than numbers.

“While the men in stripes (unload) the Caroline, the skipper walks among them. (He) talks to them, (getting) to know them and their sad secrets,” according to the story. “(Leale) notices whether they handle freight like men who work from choice or from necessity.”

If the skipper was pleased with their work ethic, “he goes after a parole for that man. It has often taken the skipper years to get the parole, but he gets it. … He puts a (bug) in the warden’s ear, or the governor’s ear, and he assaults the combined ears of the State Board of Prison Directors and (since) everybody loves him and class him ‘Cap,’ what are they going to do about it?”

Ship jobs awaited those needing reentry help

Back then, for a prisoner to be paroled, he had to show he had a job waiting for him outside the gates.

“‘Well, how about his job?’ (they ask). ‘He’s got a job,’ retorts the skipper. ‘Where?’ (they ask). ‘Deckhand on the Caroline,’ (the skipper responds).”

According to Sunset Magazine, the ship employed quite a few ex-convicts.

“But that’s Captain Leale. He’s never happy unless half his crew are ex-felons. He will tell you that 90 percent of them make good. He puts them on their honor, after he’s given them that job they need in order to be paroled,” the magazine reported.

“When a convict the skipper knows for a ‘pretty decent fellow’ comes out of ‘stir’ with a suit of the cheap prison-made ‘free’ clothes that shout his shame to all the world, Leale takes him in tow, leads him to a clothing store and stakes him to a suit of store clothes that will hide his history. Next he goes after a job for that man. Stewards, waiters, deckhands, freight clerks on the river and bay steamers – lots of these are Leale’s proteges. He even scattered some of his Submerged Tenth on farms up and down the San Joaquin (river) and the Sacramento.”

Leale’s helpful nature extended to staff as well

He also showed his appreciation to the prison employees and their families.

“Every May-day, the children and wives of the guards and officials at San Quentin are his guests for an all-day cruise around San Francisco Bay. He has on his free list, also, a few orphan asylums and charitable organizations whose specialty is children. He gets his fun watching other people wax happy, particularly children and the Submerged Tenth.”

The magazine’s profile on Leale describes him as quick of wit, “rich in sea yarns and humorous anecdotes.”

“He is a jolly old sea-dog, a mimic, a monologist, a rare raconteur and all-around entertainer,” the magazine reported. “He might have won a place for himself on the vaudeville stage, but he would rather stay at home and jolly his friends and money with problems in social economy. A thousand (dollars) a day wouldn’t bring the skipper away from San Francisco and the Caroline. She’s a good old craft, for all her years, and Bill Leale loves her. They have worked together so many years, they understand each other.”

Leale’s final days full of loss

Leale lost his wife Lily in 1915. He lost his other great love, the Caroline, just three years later.

“Last month, the old stern-wheeler Caroline succumbed to the ravages of fire and sank at her anchorage of Sausalito. The origin of the fire is unknown as there was no one on board,” reported The American Marine Engineer, March 1918.

Later that same year, Leale died and was buried alongside his wife in an Oakland cemetery.

Transportation moves from rivers to trains to roads

With the evolution of transportation methods, rehabilitation efforts also evolved. By 1920, the automobile had become popular and a major effort was put into building a network of reliable roads. Incarcerated crews were some of the first to build those roads in rough, steep terrain. Later, many of those road camps converted to harvest camps and eventually fire camps, which are still in use today.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.