By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Office of Public and Employee Communications

Those who walk the toughest beat in the state deal with people who made very poor choices. From car thieves to those facing insurmountable medical debt, the reasons some of those early inmates landed in state prisons are varied. The following inmates, who served their time in the early 1900s, range from actors who turned to crime, a movie fan who emulated the silver screen’s cowboy bandits and another inmate who turned his prison experiences into a play to urge reform.

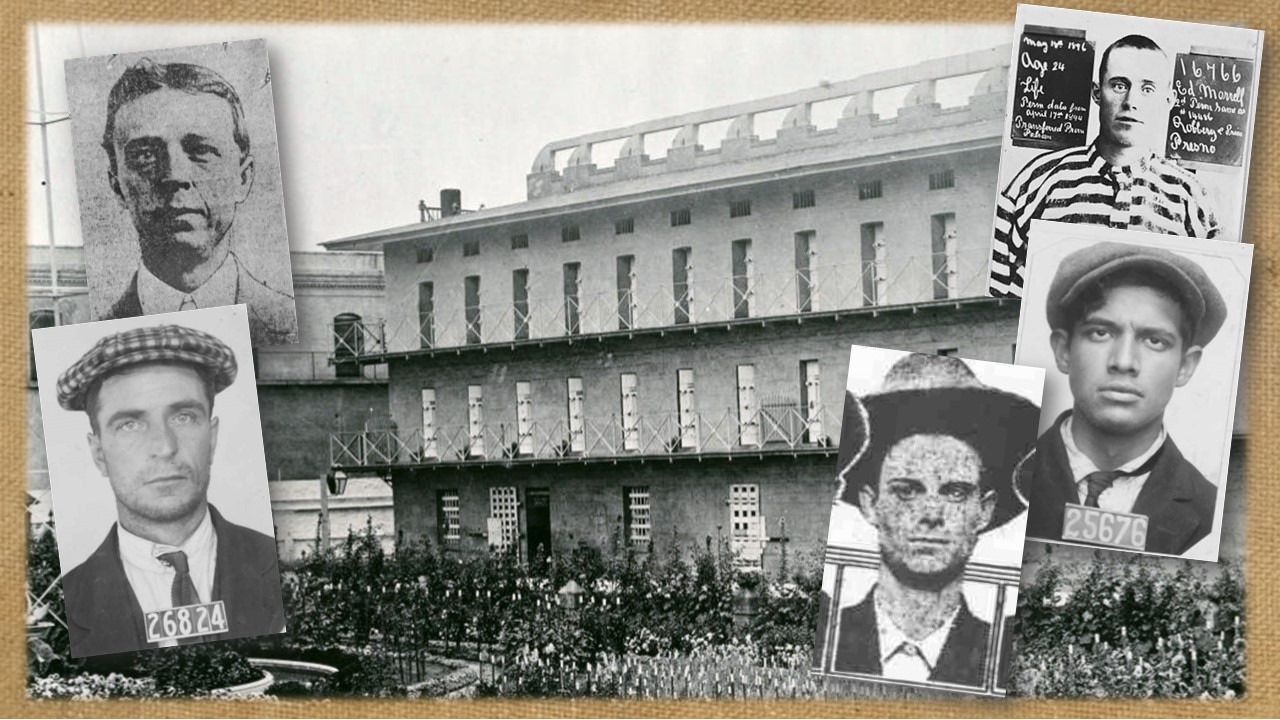

Actor can’t control auto obsession

Actor George Kelly had an affinity for vehicles, even if they didn’t belong to him. Much like the “mania” experienced by Disney’s Mr. Toad character, Kelly was obsessed with automobiles.

“Under the defiant eyes and sullen bearing of George Kelly, there lay a heart that could be touched. As he stood up for sentence in Judge Willis’ court today the mention of the word ‘mother’ brought tears to his eyes,” reported the Los Angeles Herald, Sept. 25, 1913. “Kelly broke down and wept. He was given six years in San Quentin for stealing the automobile of Walter J. Meeks. Nothing had stirred him until the pleas of leniency on account of his aged parents were heard. Then his feeling overcame him.”

When he was released on parole, he wrote a series of stories for newspapers titled “Stories of a Reformed Auto Thief.”

Despite his apparent rehabilitation, he ended up behind the wheel of another stolen vehicle. This time, he committed his crime with more flair.

“Made up as an Apache Indian, George A. Kelly, a motion picture actor, was locked up in the City Jail today on a charge of grand larceny,” reported the Herald on Sept. 9, 1916. “According to police records, Kelly was sentenced (in 1913) to serve a term of six years in San Quentin prison on a charge of stealing an auto. He was placed on parole a short time ago.”

He was received in 1917 and discharged in 1919. But, by 1927, he was again behind bars, this time in Folsom Prison serving a 1-to-5-year sentence under the inmate number 15008.

Actor turns to crime to pay doctors

George Thompson was the father of two children when his wife was diagnosed with a serious illness requiring life-saving surgery. Without the means to pay for the procedure, he turned to crime in 1909, he claimed.

When the actor was finally caught after weeks of residential burglaries in Los Angeles, he confessed and cooperated with authorities to recover the stolen property. He used his acting skills as part of his burglary schemes.

“Much of this, it is believed, can never be recovered,” reported the Los Angeles Herald, July 23, 1909. “All the solid gold jewelry, Thompson states, was melted and sold in lumps. … Thompson’s method in his criminal career appears to have been to gain admission to houses in the guise of a gas inspector or special policeman. He worked chiefly in the daytime, riding a bicycle.”

His crimes earned him time in San Quentin.

“George Thompson, who was an actor two months ago, was today sentenced to serve three years in San Quentin for burglary. Thompson confessed when he was brought into court today, telling the court that he stole in order to secure means to send his wife to the hospital for an operation which the physicians said was necessary to save her life,” reported the Sacramento Union, Aug. 28, 1909. “His wife, with two babies in her arms, sat in the courtroom while he made his confession. Thompson’s attorneys asked for an immediate sentence. The police were mystified for six weeks by a series of burglaries which occurred in the (residential) district, to which Thompson confessed.”

Police found a large cache of silver buried in the actor’s backyard, according to the Associated Press.

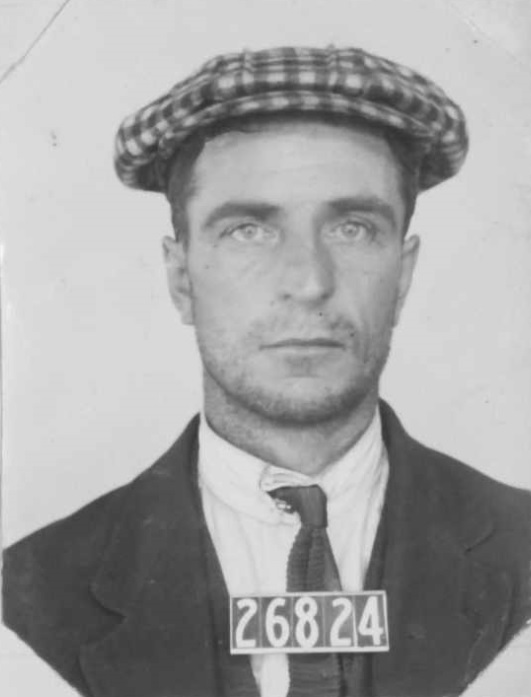

Young actor sentenced to Folsom

He was many miles from Chicago when 18-year-old Edward Cole was incarcerated after being convicted of burglary charges.

“Edward Cole, 18, and formerly a member of a Chicago theatrical company, pleaded guilty to a charge of burglary (in Stockton) before Judge Norton this morning, and was sentenced to serve three years at Folsom,” reported the Sacramento Union, April 24, 1912. “His companion, William Hoin, who assisted in the burglary, was sent to San Quentin for three years.”

Real life imitates art

Two men who were accustomed to donning cowboy hats and riding into the sunset after robbing stagecoaches and banks, at least on screen, reckoned the criminal act must be fairly easy so they gave it a try. The actors found reality was much different.

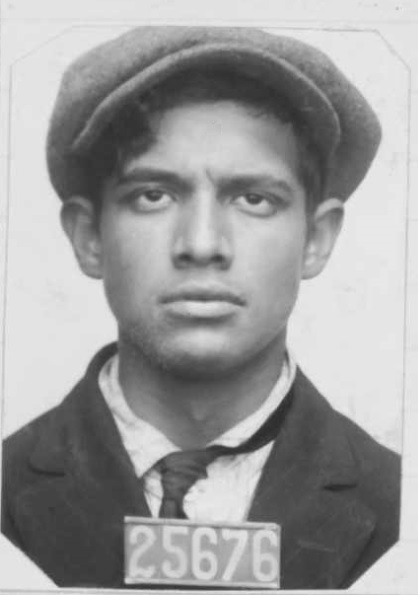

Thomas Green, who went by C.U. Thomas in films, and Paul Case robbed a bank in Blythe on Dec. 4, 1913, but their pistols weren’t firing blanks. Green said he accidentally squeezed the trigger, ending the life of cashier William Bowles. They grabbed the $5,000 in loot and fled.

“(The) young motion picture actors … were caught asleep in bed (and are awaiting) transfer to Riverside, … where they will be called to face trial for the results of an alleged effort to duplicate in earnest the bandit roles both had played in film,” reported the Daily Missoulian, Dec. 6, 1913.

“After robbing the bank the two men escaped through the Colorado river bottoms on horseback,” reported The Associated Press, Jan. 14, 1914. “Posses mounted and in automobiles followed them to El Centro, where they were found asleep in a lodging house with their plunder, weapons and clothes scattered over the floor. During their trial they told of their roles in film hold-ups and how they planned the Blythe robbery, thinking it must be easy in real life.”

According to news accounts, Green wasn’t his real name but the condemned man refused to reveal it to the authorities. Before his execution, a chaplain prayed over him. He said, “(I) never heard a prayer in (my) whole life,” according to The Day Book, April 13, 1914.

He was hanged on schedule on April 3, 1914, according to the United Press report published in the Riverside Daily Press.

“Thomas Green, murderer of Wm. G. Bowles, cashier of the bank at Blythe, was hanged here at 10 o’clock this morning. He met death bravely, without a sign of weakness,” the report states. “Green, along with Paul Case, attempted to rob the bank at Blythe and shot and killed Bowles when the latter attempted to sound the alarm. The actual shots were fired by Green, and he received a death sentence while Case was let off with life imprisonment. … Green mounted the scaffold at exactly 10 o’clock. As the cap was being adjusted, he thanked Warden Johnston for his kind treatment, and said: ‘I will not reveal my real name. My mother and father are good people. They raised me properly and gave me every advantage. I want to go to my death with my identity unknown. My parents know nothing of this affair and now I know they never will. I am sorry I killed the cashier, but I fired before I realized what I was doing.’”

According to other news accounts at the time, Green was 23.

It was the first execution for “San Quentin’s new hangman, Guard Nealon. It was without incident,” reported the Los Angeles Herald, April 3, 1914.

Cowboy movie fan gets prison time

“Cowboy nonsense sends him to jail,” declares the headline of the San Pedro Daily News, March 27, 1914. “James Molette, better known as ‘Blondie’ charged with embezzlement for failing to return a rented horse … was found guilty by a jury and was immediately sentenced to one year in San Quentin by Judge F.F. Oster.

“Molette simply grinned when he was sentenced by the court and was informed that if he kept up his cowboy nonsense he would probably end his career at the end of a rope. The lad had been given previous opportunities to behave.”

Molette not only swiped the horse, but a cowboy outfit as well.

“After stealing a cowboy costume from a moving picture actor at Los Angeles, Molette made a dash for the desert on his stolen horse bent on becoming a bad-man, so he confided in the officers after his arrest.”

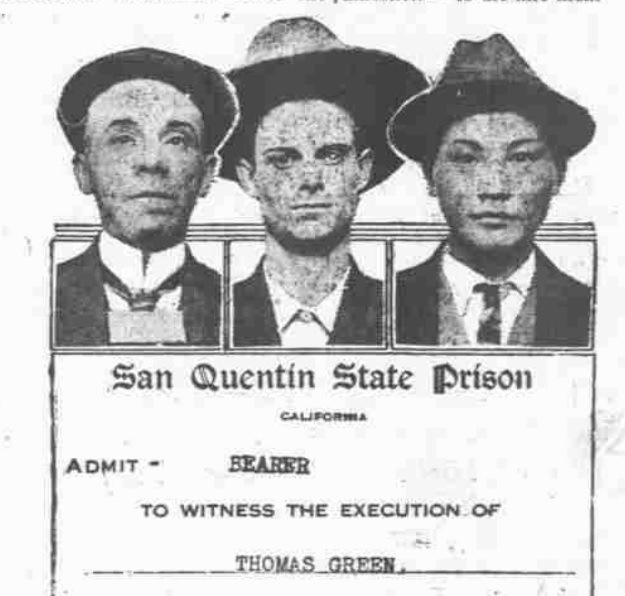

Turns prison experience into crusade for reform

In 1903, the members of a committee of the State Assembly investigated the use of strait-jackets at San Quentin State Prison. During their inspection of the incorrigible cells, they questioned one of those locked in the cell.

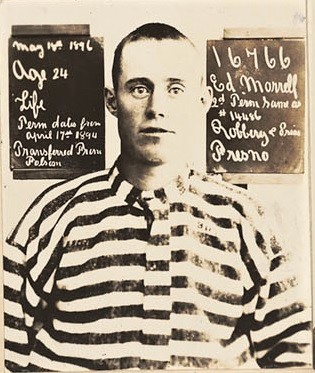

“Morrell, one of the worst characters in the prison, was questioned. He maintained that (the dungeon) was injuring his eyesight but is understood that the committee was convinced beyond doubt that his allegations were without foundation,” reported the San Francisco Call, Feb. 25, 1903.

One of the committee members voiced opposition to the use of strait-jackets.

“There is no doubt that the strait-jacket is an instrument of torture and should be abolished at once. It is a blot on the name of California and a disgrace to the State prisons,” Assembly member J.O. Traber told the newspaper.

Morrell was convicted of highway robbery and sentenced to life in prison in 1894. He was a member of the notorious Sontag-Evans gang of train robbers.

While incarcerated, he made three attempts to escape. Through rehabilitative efforts while inside, he was eventually pardoned.

“(He) finally liberated himself by a remarkable personal transformation (to) become a powerful factor in the abolition of the tortures by which he suffered,” reported The Day Book, July 7, 1914. “(He’s been) active in prison reform measures for (the) past seven years.”

Morrell “could not be broken by strait-jacket or tricing irons (and) served five (years) of his (sentence) in the dungeon.”

“Ex-Convict, Now an Actor, Is Champion of Prison Reform,” declared the headline in the Los Angeles Herald, July 22, 1914. “Championing the prison reform movement, Ed Morrell, who himself served sixteen years of a life sentence in San Quentin, five of which were passed in (the incorrigible cell), is to address several women’s clubs here next week. He will also present a sketch showing the need of prison reform based on actual experiences from his own life. It is called ‘The Incorrigible,’ and has been recognized as a potent educator for the cause. Morrell will appear in it, at the Republic Theater, next week. The play is taken from real life, from actual happenings while he was incarcerated behind the prison walls.”

According to Morrell, things began to change in prison when a new warden was appointed. The warden gave him another chance and Morrell seized the opportunity, eventually becoming the head inmate trustee at San Quentin. He was released in 1908.

“Bestiality always kills itself,” he told The Day Book. “Tortures bring public revulsion. Suffering is converted into the most power weapon against the inflicting agency. World history proves that, and penitentiary history is confirming it. Only institutions based on regard for human welfare, even that of the humblest and most despised of men, can justify their existence to the public and truly pay for their support.”

After his release, he lobbied the “legislature to enact a workable parole law, and became the father of the famous honor system among prisoners. He is given the credit for causing the honor system to be adopted by Arizona and Oregon,” reported the Dearborn Independent, June 4, 1921.

Morrell testified before legislatures in Pennsylvania and California as well as the U.S. Congress. He befriended former SQ inmate Donald Lowrie, an author and fellow advocate for prison reform. He also met and befriended famed author Jack London. In London’s book, “The Star Rover,” he based a character on Morrell, according to “The Chronicles of San Quentin,” by Kenneth Lamott.

He founded the Twentieth Century Prison League to promote prison reform. It was later taken over by the Bureau of Commercial Economics, an “altruistic motion picture organization that operates on an international scale from Washington,” and turned into the organization’s Department of Prisons. Morrell was named its director. He urged the state prison system to adopt modern methods of incarceration to rehabilitate offenders rather than simply punish them.

“A very large proportion of persons sent to our prisons need medical treatment more than they do punishment. Instead of impairing them further, as our system does, we should repair them and fit them for honorable combat with life,” he told the Independent in 1921. “If the mind is in need of repairs that can be made, send him to a psychopathic infirmary; if the body is the point of weakness, to the operating table or to a rehabilitation hospital. Turn out none until they are well and trained in a trade that will enable them to earn honest livings.”