From retired CDCR Secretary Scott Kernan to Parole Agent Harvey Watson, some choose to follow the career paths of their parents. Kernan’s mother, Peggy, was the first female captain at San Quentin. Watson’s father, also named Harvey, was a parole agent in the Los Angeles area in the 1970s. There have been many examples of this throughout the department’s long history, particularly when looking at the Duffy family at San Quentin.

Duffy family trades farm plows for badges

“My father, William Joseph Duffy, owned a small farm … just across the bay from Point San Quentin (but he) didn’t like farming. … One day the late Sheriff R.R. Veale, of Contra Costa County, an old family friend, told my father there was a vacancy at San Quentin, a guard job paying $50 a month,” Clinton Duffy wrote in his 1950 book, “The San Quentin Story.”

William J. Duffy had been a justice of the peace for 10 years so was hesitant about applying for the job since he was instrumental in sending many to prison.

“Don’t give it a worry,” said Veale. “They’ll respect you all the more.”

William Duffy took the job and moved his wife and five children to the prison in 1894. Clinton was born four years later. William, according to most accounts, worked at the prison for 30 years.

Life in San Quentin village

“San Quentin, in the 1890s, was an isolated town on a peninsula. It really was a village built just outside the prison walls, with San Francisco Bay on one side and San Pablo Bay on the other. Guards were paid $50 a month when Dad first went to work there and it was some time before a raise was given. Besides, the men worked seven days a week with no day off and no vacations,” Alma Duffy Leathers Zang wrote in 1931 family history. Alma is Clinton Duffy’s sister.

“But supplies that were given to the employees, at cost by the state, helped. A large box of vegetables, grown on the prison grounds and tended by prisoners, was delivered to each family for 10 cents a box. When tomatoes were in season a large lug box was available for 10 cents. The children had hair cuts at the prison barber shop, by prisoners, free.”

Father sets example at young age

After the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, William Duffy guarded their house. The stood in front, armed with a rifle.

“The San Francisco Police had evacuated the jails, loaded the prisoners into a boat, and had anchored offshore opposite our house,” Clinton Duffy wrote. “There was a rumor that the prisoners were plotting to seize the boat because the authorities wanted to lock them up inside the prison until order was restored in San Francisco.”

The younger Duffy recalls hearing the county jail prisoners shouting from the boat deck. In case there was trouble, Warden John Edgar had prison staff patrolling the waterfront.

“Now look kids,” said William Duffy. “Go on and play and forget those poor fellows on the boat. They’re probably wet and hungry and scared, and they’re not going to bother anybody.”

There was no trouble and the boat moved on after a few days.

“But I never forgot the incident, and ever since I’ve thought of men behind bars as my father saw them – human beings in trouble and needing a helping hand,” wrote Clinton Duffy.

The book details young Clinton Duffy’s paper route that included the front gate, up to the warden’s office and over to the captain’s desk.

“I didn’t dare lose a paper when the prisoners were around because the local papers were contraband,” he recalls.

San Quentin childhood was ‘a little different’

“We climbed forbidden trees, usually the pomegranates around the warden’s house, or those in a tiny orchard below the east gate gun tower. There was one favorite pear tree there from which we stole fruit. … Childhood in San Quentin was a little different,” he wrote. “The neat little blue suits I wore as a boy, for instance, were made from my father’s worn-out guard uniforms.”

The kids often climbed the hill to catch a view of the main yard and the men wearing stripes.

“I don’t think we ever realized, as children, that we were living and growing up in a constricted world where … family laughter and horseplay served as a convenient and necessary mask for the tension under which our parents lived,” he wrote. “Even the daily risks my father faced were not very real to me.”

Fates of two San Quentin families intertwine

The Carpenter family was a fixture at San Quentin with Leander Carpenter working as a guard for 20 years.

His son, J.H. “Johnny” Carpenter, was the Duffy family’s friend and neighbor. Carpenter followed in his father’s footsteps and became a guard at San Quentin when his daughter, Gladys, was 4 months old. But he didn’t stay in the job very long. In 1902, when his daughter was 3, he took another job and the family relocated to San Francisco.

The 1906 earthquake changed the family’s fate, finding them returning to San Quentin to live with Leander Carpenter. J.H. Carpenter returned to work at the prison as a guard.

Gladys Duffy recounted the events in her memoir, “Warden’s Wife,” published in 1959.

“We were herded aboard (a lumber schooner) with other refugees and set sail for Marin County. Although it was now well past sunset, it wasn’t dark. The glow from 10,000 fires lit up the sky,” she wrote. “I was asleep on my feet when we finally arrived at Grandfather Carpenter’s house, but his hearty welcome roused me. ‘Come in! Come in! There’s plenty of room.’ After just one week at San Quentin, I was convinced that it was the finest place in the world. Best of all, I had plenty of playmates (with) nearly a dozen youngsters close to my own age.”

Leander Carpenter passed away in 1918.

“He was one of the most popular employees of the institution, and numbered among his friends without exception every man with whom he had ever associated. He is survived by his widow, Mrs. Jane Carpenter and four children, Mrs. A. Berger, Mrs. William Davison, C. T. and J. H. Carpenter. The deceased was a native of Tennessee and 69 years of age,” according to the Marin County Tocsin, Feb. 9, 1918.

Clinton Duffy returns to prison roots

When the U.S. entered World War I, Clinton Duffy served in the U.S. Marine Corps. After he was discharged, he married Gladys on Dec. 31, 1921.

Clinton Duffy worked a few odd jobs but eventually found himself returning to his roots, taking a job at the prison.

He became the office assistant to San Quentin Warden James B. Holohan, “a hulking, curly haired, and rather handsome man, (who) had come to San Quentin two years (earlier) with a reputation as a poker-faced, two-gun peace officer of the old west,” Duffy wrote.

The younger Duffy recounts his training during his first seven years as the office assistant.

“My training period also involved me in the investigation of suicides, hunger strikes, mental breakdowns and cases in which some trigger-happy guards wounded or occasionally killed prisoners who ran amok in the yard,” he wrote. “I spent a lot of time too on what we used to call the ‘prima donna’ circuit, a routine that involved occasional checkups on prisoners who made news almost every time they sneezed.”

Duffy family takes village children under wing

Gladys was very involved in the San Quentin village community and became a trained Camp Fire Girls leader.

“Twelve winsome little bluebirds in white middies with bright blue ties sat in a circle on the floor of one of the committee rooms at Scout Hall Thursday afternoon while Gladys Duffy told them stories. Across the hall, nine Camp Fire girls of the Nimaha group were playing games with their hostesses, the girls of the Chivasumi group of Mill Valley. The guests were all from the village of San Quentin, daughters of guards at the prison,” reported the Mill Valley Record, Dec. 31, 1927.

“Under a pretty tree were heaped pink bags of nuts, candy and fruits. Ice cream and cake were waiting in the serving room. Mrs. M. G. Irvin and Mrs. Gladys Duffy of San Quentin drove the cars that carried the guests.”

She also became a school teacher and later the principal at San Quentin public school, noted as such in a 1930 newspaper article about the May Day celebration. She also worked in the prison, acting as the director of plays put on by the inmates.

In August 1932, J.H. Carpenter suddenly passed away at his San Quentin home.

“I couldn’t believe my father had died. Outwardly in perfect health and so vibrantly alive, it seemed incredible that he should have suffered a fatal heart attack. I kept thinking, ‘This is just a bad dream,’ even after I saw the flags of the prison flying at half mast the next morning, even after I saw five thousand prisoners standing with bowed heads while taps was played that Sunday afternoon,” Gladys Duffy wrote in her memoir.

Getting to know a serial killer

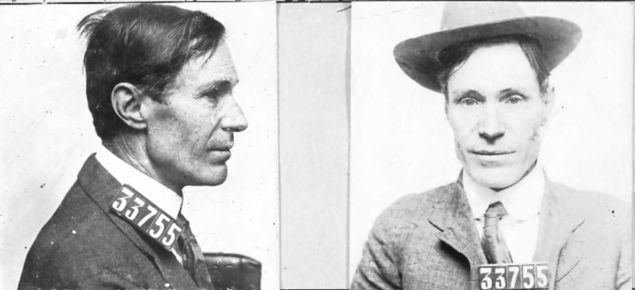

One such prisoner Duffy kept tabs on, at the insistence of Warden Holohan, was James “Bluebeard” Watson who admitted killing 20 women.

Duffy writes he got to know Watson very well over the years.

“Bluebeard was strangely proud of the fact he charmed a score of women to death, He urged me to remember that ‘soft words make for a soft touch,’” he wrote. “During his 20 years in San Quentin, Bluebeard puzzled and exasperated four wardens. He was a sort of penological museum piece, classified as a homicidal monster, yet curiously gentle and shy, and he fascinated the public.”

Watson avoided the death penalty by striking a deal with the district attorney. Since none of the bodies had been found, he offered to produce one body in exchange for a life sentence. He led detectives to a grave in the desert outside Los Angeles, where they found victim Nina Lee Deloney.

“To this day ,nobody knows exactly how many women he slew or where he hid their bodies. Despite his fearful record, this five-foot-five man with the square face, underslung jaw, and wispy hair continued to attract women. I have no doubt he could have had another dozen eager wives if he had been set free,” he wrote.

While Watson died in 1939, he ensured there would be one last piece to his penological puzzle.

Watson got the last laugh

Watson named Duffy as the executor is his will. He claimed a hidden stash of cash and jewels worth $80,000 should be divided between two charities and four prison staff members. The location of the hidden treasure would be “revealed in another document.”

“I never found this other document, or any other clues,” Duffy wrote. “I don’t think there ever was any hidden wealth. But even (over a decade after his death), I still get an occasional letter from indignant families in other states, including relatives of Bluebeard’s victims, demanding their share of my spoils. I always tell them what he really had (was) a trunk full of florid prose and a prison bank account with $18.70. I like to think of Watson, in the twilight of his life, secretly enjoying the gossip about this wealth and giggling to himself as he wrote his will. There, at least, was a document from his typewriter that no one would ignore.”

Duffy becomes warden, focuses on rehabilitation

Warden Holohan asked Duffy to accompany him to the execution of mass murderer Gordon Northcott on Oct. 2, 1930. Holohan had grown weary of this part of his duties, according to Duffy.

“Warden Holohan, pale and plainly suffering, … turned his eyes away from the rope. Northcott stumbled and sagged, and the guards carried him up the steps. I heard him weeping and (begging for a prayer to be said for him). Warden Holohan raised his right hand, a tired and unwilling hand, and it was over,” he wrote. That night, sitting with his wife, Duffy vowed never to do that again and said he was glad he wasn’t warden.

In 1940, Clinton Duffy was appointed “temporary” warden of the prison, slated for a 30-day assignment to the post. He restarted the inmate-produced newspaper, dubbing it The San Quentin News.

Duffy orders prison desegregation

In 1945, Warden Duffy made headlines by ordering racial integration in the dining hall.

“Eight hundred white San Quentin convicts refused tonight to eat with 477 (non-whites) and waited until the latter had finished before filing into the mess hall,” reported the Daytona Beach Morning Journal, March 27, 1945. “The silent demonstration was in sharp contrast to last night’s mess hall riot in which one inmate was stabbed and three were injured. The protests were directed against Warden Clinton Duffy’s order (removing segregation during meals).

“About 1,300 whites ate with the (non-whites) tonight. The 800 dissenters were allowed to dine later. Prison attaches estimated this extended the night mealtime about 20 minutes. Warden Duffy, however, insisted he would not go back on his order lifting segregation. His order was backed by the state prison director, Richard A. McGee, and by Governor Earl Warren.”

“When he was appointed temporary warden at age 42, he was the youngest warden of a major prison in the nation,” reported the New York Times, Oct. 14, 1982. “He was warden at San Quentin until 1952, establishing himself as an innovative and humane director of prison life and earning the respect of penologists and inmates alike. He then served for 10 years on the California Adult Authority (before) retiring in 1962.”

Gladys Duffy passed away in 1969 at 69 years old. Clinton Duffy passed away in 1982 at 84 years old.

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.