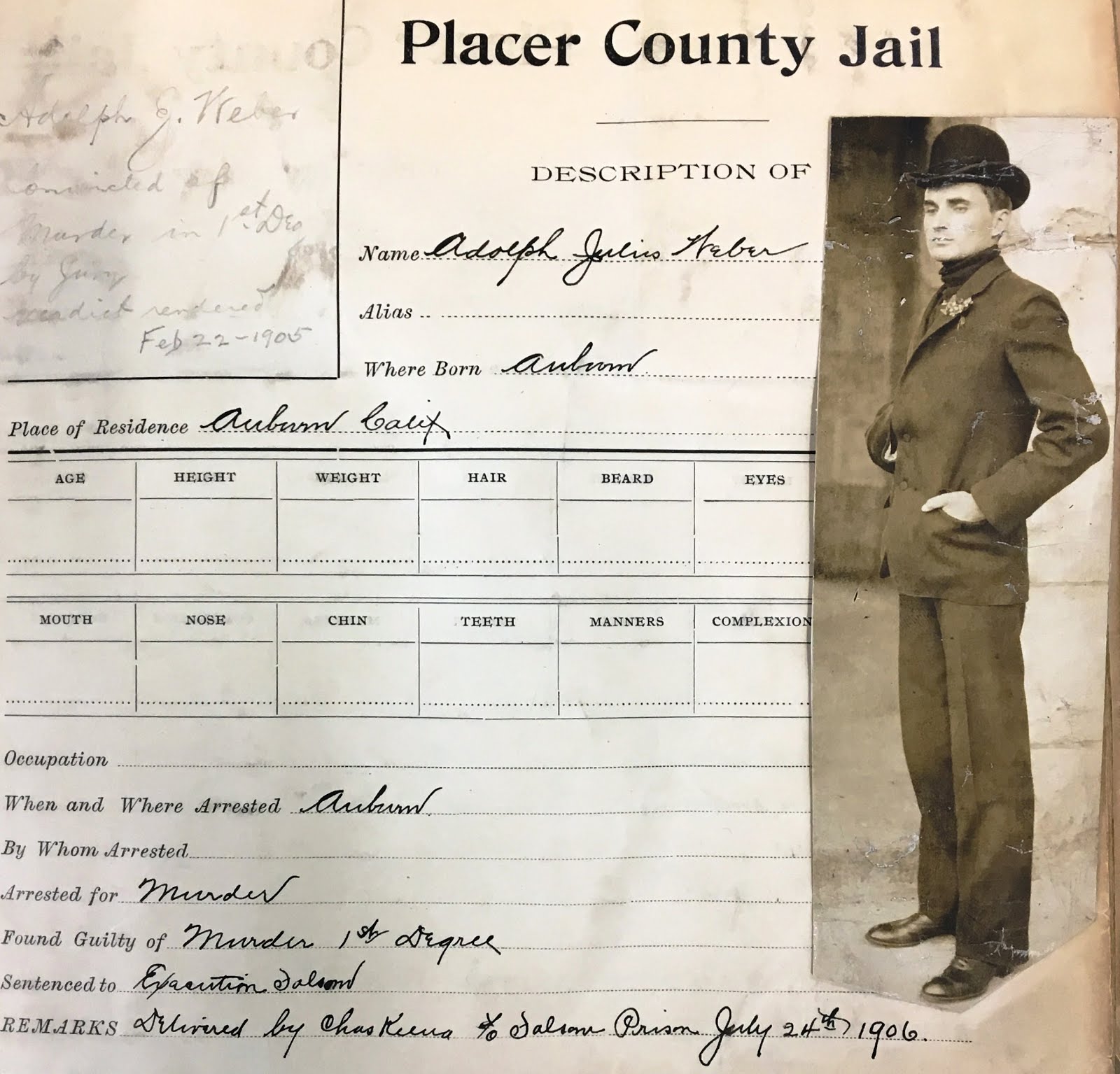

Attorney General tries family murder case

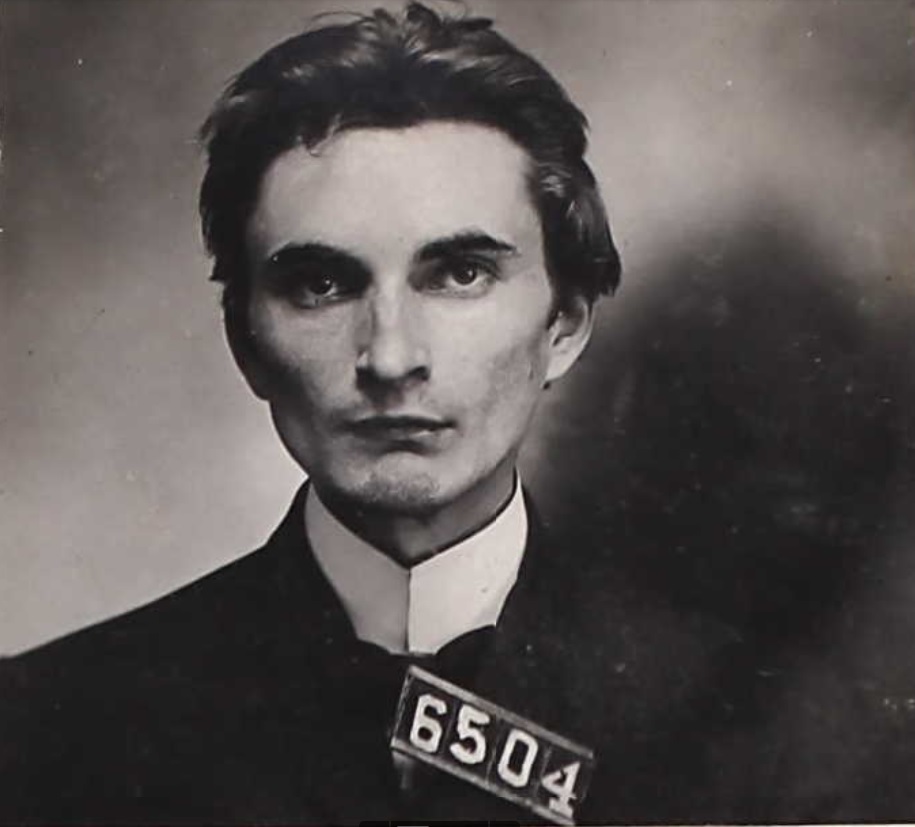

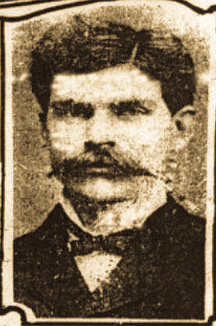

Adolph Weber was a young man from a well-off family. Why he chose to throw a mask over his face and rob a bank in 1904 is a matter of speculation. Even more shocking was the slaughter of his parents, 18-year-old sister Bertha and 8-year-old invalid brother Earl.

Adolph was the sole beneficiary to the family fortune of more than $2 million in modern terms. The Weber case set in motion new laws to prevent family members convicted of murder from inheriting their victims’ assets.

Decades later, additional laws were created to prevent criminals from profiting from their crimes. Weber’s case, prosecuted by the Attorney General at the request of the Governor, went all the way to the state Supreme Court and finally finished at the end of a rope at Folsom State Prison.

Wealth doesn’t stop rebellious son

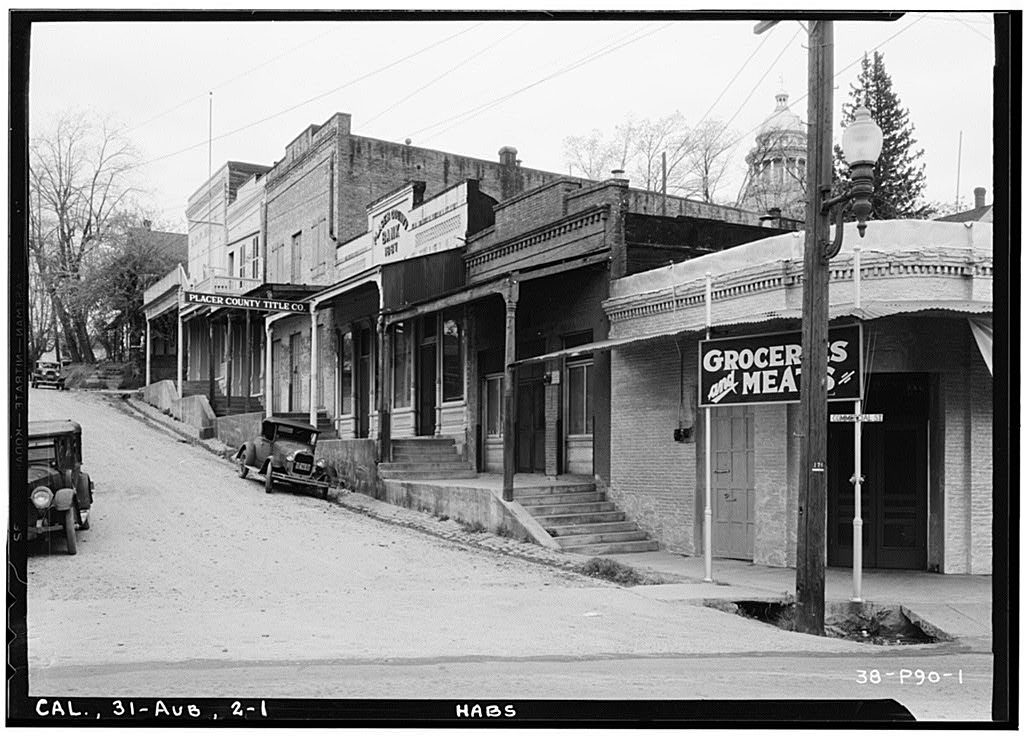

The Auburn Brewery, owned by German immigrant Julius Weber, was a hub of activity in the late 1800s.

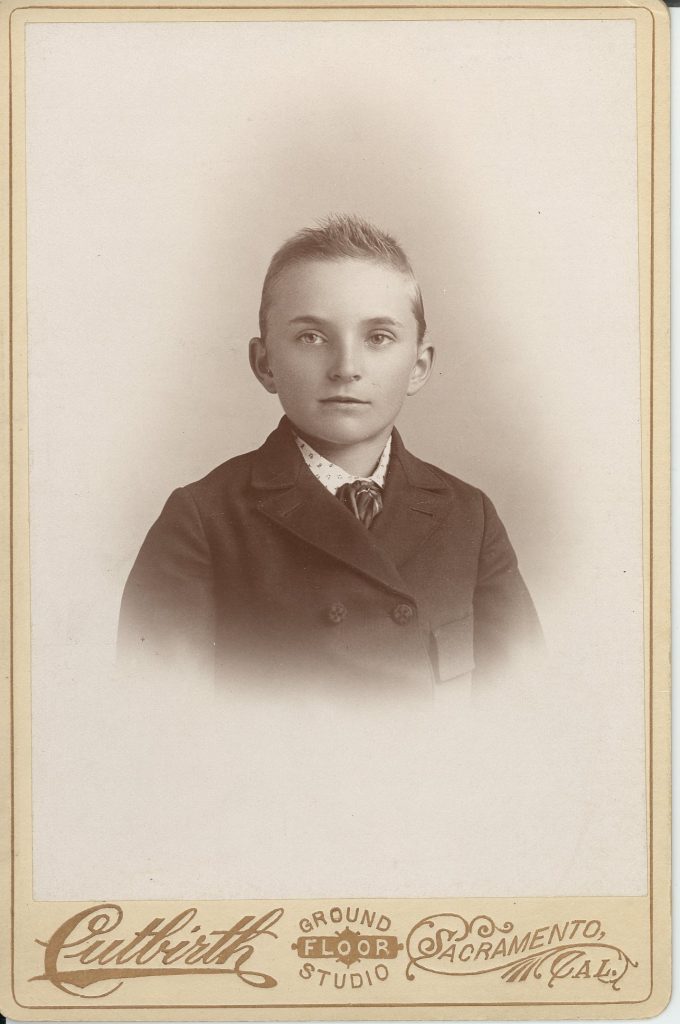

In 1883, Julius married Mary Meyer in Auburn. A year later, the happy couple welcomed their first child, Adolph.

Weber sold the business in 1895, saying he wanted to take care of his family.

By all accounts, Adolph was a normal child until his mid-teens. That’s when some accounts, including one by the family physician, claim he began killing and torturing small animals.

His actions escalated while his mood soured, finally coming to a head when he was 20.

On May 26, 1904, a masked Adolph Weber “entered the Bank of Placer County (in) Auburn, and drawing a revolver, ordered the employees to hold up their hands. He then stole $5,000 and disappeared. At that time, many circumstances pointed to Adolph Weber as the robber,” according to the 1910 “Celebrated Criminal Cases of America,” by Thomas Samuel Duke.

At the time of the robbery, Julius Weber noticed a homemade money bag was missing from the family home. That’s when he became suspicious of his son. Six months later on November 10, the Weber home burned.

A neighbor broke down the locked-door during the blaze and found two women in the front room. Both had been shot. The little boy, badly beaten about his head, was clinging to life but succumbed to his injuries a short time later. The next day, the father’s body was found.

Suspicion fell on the family’s only surviving member – Adolph Weber.

Heir to family fortune suspected of murder

“When the fire was first discovered, a man named George Ruth broke in the front door and found the bodies of Mrs. Weber and Bertha in a room which had not been reached by the fire at that time. Bullet wounds were found and they had evidently been dragged into this room after being killed and (someone tried setting) their clothing on fire. The little invalid boy, Earl, died shortly afterward from the effects of blows delivered on his head by some blunt instrument,” according to the book.

The next day they found the 52-year-old father’s body in the burned-out home. He had also been shot.

On Nov. 12, 1904, only two days after the fire, Adolph Weber was arrested and charged with murder. His aunt, Mrs. Snowden, said the young man threatened her when she asked if he knew more about the killings. “Your turn will come next,” he told her.

During the trial, Snowden revealed she and her sister were extremely close but Adolph was a source of trouble for his family. The Snowdens lived next door to the Webers.

Tale of a troubled youth

“Adolph, however, kept the family in almost constant turmoil,” she testified, according to the San Francisco Call, Nov. 17, 1904. “He annoyed his father and sometimes would not speak to his mother. He was hateful and stubborn, but I never saw him strike anyone except his poor little crippled brother.

“Last Thursday, (Adolph) was unusually ugly. I went over to see my sister and took little Earl home to his mother. When I walked over to the house, my sister and I exchanged loving greetings.

“I sat and talked with her for a while, (when) Adolph came into the yard. His mother said, ‘Dolphy, will you go down to the market and bring home some meat for dinner? Your father has been working very hard this morning digging postholes.’ Adolph passed her by without saying a word. She asked him three times and finally he snapped out a cross and ugly ‘No.'”

According to the testimony, the mother told Snowden, “Adolph is so mean, he will kill us all yet.”

Adolph’s temper was well known in the family

“Adolph was hateful to his people. He thought they were in his way. Bertha was afraid of him, (saying) to me, ‘I think Adolph is mean enough to kill anyone.’ The last time I saw Bertha was Friday afternoon, when she called to see me on her way from school. She was very happy and full of fun,” said Snowden.

She saw Julius Weber a few hours before the fire. “It was on that awful Thursday, about 5 o’clock, (when Julius) came over to my place for a pail of water. He was in a pleasant state of mind and talked and joked with us. He not only drew a pail of water for himself, but he drew several for us. (Then) he bade us a cheerful ‘good night’ as he went out through the gate.”

Investigators follow the clues

After the fire, investigators began retracing young Weber’s steps. Throughout the investigation and trial, Adolph Weber appeared indifferent, according to newspaper accounts at the time.

When told of the discovery of gold coins buried at the family property, Weber said, “Oh, I thought you had discovered the motive for the murder. The bank robbery is a trivial matter. It’s not bothering me. It’s the other case I am thinking about. If I did take it, it was not because I needed the money, but only to see what I could do,” according to the book, “Folsom’s 93,” by April Moore.

The case quickly came together as outlined in the court proceedings.

String of evidence leads to Adolph Weber

The evening of the fire, Adolph purchased a new pair of pants from a store in town. According to police, he then wrapped up his old pants and rushed to the burning home. Several witnesses reported seeing Adolph break a window with his hand and throw the bundle into the flames. The broken glass severely cut his hand and “he became weak from the loss of blood and spent the remainder of the night at the home of Adrian Wills,” according to the 1910 book by Duke.

The discarded pants, which were found to be stained with blood, also hadn’t burned.

On Nov. 21, investigators found a revolver hidden under the flooring of the barn behind the family home. The revolver held used shells and the pistol butt had blood and the little boy’s hair stuck to it. Police traced the gun to San Francisco.

“(Pawnshop proprietor) Henry Carr … positively identified this pistol as one he sold to Weber in July 1904,” the Duke book states.

On the night of the fire, J.A. Powell said at about 7 p.m. he saw Weber rush into the American Hotel’s washroom and begin scrubbing his hands, then fled without drying them.

On Nov. 23, officers searched the Weber home and unearthed a “5-pound larder can full of $20 gold pieces, which was evidently the proceeds from the bank robbery.”

The pistol used in the robbery, recovered when the robber discarded the weapon as he fled, was eventually traced to a Sacramento pawnbroker who also identified Weber as the buyer.

State Attorney General takes over case

The case garnered headlines across the country. California Governor George Pardee put the state’s attorney general in charge of the case.

“In January 1905, I was requested by your Excellency to proceed to Auburn, in Placer County, and assume charge of the prosecution of Adolph Weber, who was there charged by information with the crime of murder. I complied with your request and the trial opened on Jan. 27, 1905, and concluded on the 22nd day of February with a verdict of guilty, without recommendation. From this judgment and appeal was taken to the Supreme Court of this state and on the 21st day of June, 1906, the judgment was reaffirmed,” wrote Attorney General Ulysses S. Webb in his 1906 report to the governor.

On Feb. 22 a jury found him “guilty of murder with the death penalty attached.” Weber vowed to take his case all the way to the Supreme Court. When the case reached that level, the justices upheld the lower court’s decision. After his numerous appeals and a stay of execution, he was hanged at Folsom State Prison on Sept. 27, 1906.

Inheritance laws tested in court

Two days before his death, Adolph Weber wrote a check to his lawyer for $11,000, the balance of his inheritance. In modern terms, it would be the equivalent of more than $300,000. He had spent the rest on his defense and appeals.

Adolph said it was a gift but the Weber family didn’t see it that way and sued the attorney. A few years after the hanging, the attorney finally forked over the money to the family, an aunt to Adolph. In 1917, the state was finally allowed to collect inheritance tax.

“An inheritance tax case which has no precedent has just been decided in favor of the state in connection with the estate of Adolph Weber, who was hanged in 1906.

“Two days before Weber (was executed), a check for $11,340 was transferred by him to Fred Stevens (his attorney. Eventually, he turned over the money to) Annie Scott, an aunt of Weber.

“The state claimed an inheritance tax (since) the transfer of the check was made in contemplation of death, though at the time of the transfer, efforts were being made to have the death sentence commuted. The case is (unique because) the courts (never) been called upon to decide an inheritance tax, where the death was not due to natural causes,” reported the Sacramento Union, Aug. 4, 1917.

The laws regarding inheritance were changed, opening the door for future legislation barring convicted criminals from profiting from their crimes.

- Read more: Weber was the prime suspect in another murder, but was never prosecuted.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor, with special thanks to Placer County Museums

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.