As technology advances, the world tries to keep pace, including the state prison system. Today’s incarcerated population has opportunities to learn computer programming, coding and drafting. Since its founding, the state prison system has tried to rehabilitate those living inside the walls by teaching skills they can use post-incarceration.

These efforts better their chances at success when reintegrating into society. The department has also adapted to technological advancements ranging from transportation and lighting to communication and security.

Prison communication speed improves thanks to telegraph

Receiving or sending information quickly across California was a challenge in the state’s early years. Letters were sent by stagecoach and train, taking days or weeks to reach their destination. With the telegraph, and the installation of lines spanning the continent, messages could be quickly transmitted.

“The line commencing at Placerville had been started before this exciting news arrived. A company had been organized to build a telegraph line to Salt Lake. This line follows the great channel of communication from the Missouri to the Sacramento,” reported the Sacramento Daily Union, Sept. 24, 1858. “Until this line is completed, the Pacific coast, cannot be benefited by the messages received by the Atlantic Submarine Telegraph. Twenty to 24 days will still intervene between us and news from (Europe).”

The technology even factored into the Civil War but wasn’t immediately embraced by military leaders.

“At the beginning of the war, some (military) officers were opposed to (using) the telegraph, favoring the old courier plan. In constructing the first military telegraph line we, bent all our energies to break down this prejudice. Before I had completed it, following McClellan’s army into West Virginia, (these officers) came to me in high praise of its usefulness,” recalled T.B.A. David.

He was one of five managing the military telegraph service, reported the Daily Alta California, July 12, 1886.

The Civil War also helped spur the country into action to complete the transcontinental telegraph and railroad.

“The role of the telegraph and the railroad expanded (during the Civil War). Railroads rapidly transported troops and supplies. The telegraph provided near-instantaneous communication over great distances,” reports the National Archives and Records Administration.

When a new line was added near the San Quentin, corrections officials adapted to make use of the technology.

“The postal telegraph cable across the bay from this city to Oakland was laid this morning,” reported the Los Angeles Herald, Dec. 19, 1886.

Thanks to the new line, a telegraph operator position was created at San Quentin, receiving a $40 per month salary.

The telegraph even helped an incarcerated person learn a job skill.

“William Melville, the famous bank embezzler pardoned by Governor Budd, was released from (San Quentin). For years, Melville has been the (prison) telegraph operator as clerk in J.B. Ellis’ office,” reported the San Francisco Call, Oct. 25, 1898.

Prison technology shifts from telegraph to telephones

“A new and complete system of telephones will in a few days supplant the inadequate one existing at (San Quentin). The (equipment) has arrived at the penitentiary and will be in operation (soon). The new system will connect guard posts, offices and gates,” reported the San Francisco Call, March 22, 1900.

In 1917, Folsom State Prison’s telephone system was upgraded with new “phones added where required,” according to a report of the prison directors.

State offices in Sacramento were outfitted with a “dial telephone system” in 1929, according to news accounts.

Railroad revolutionizes transportation

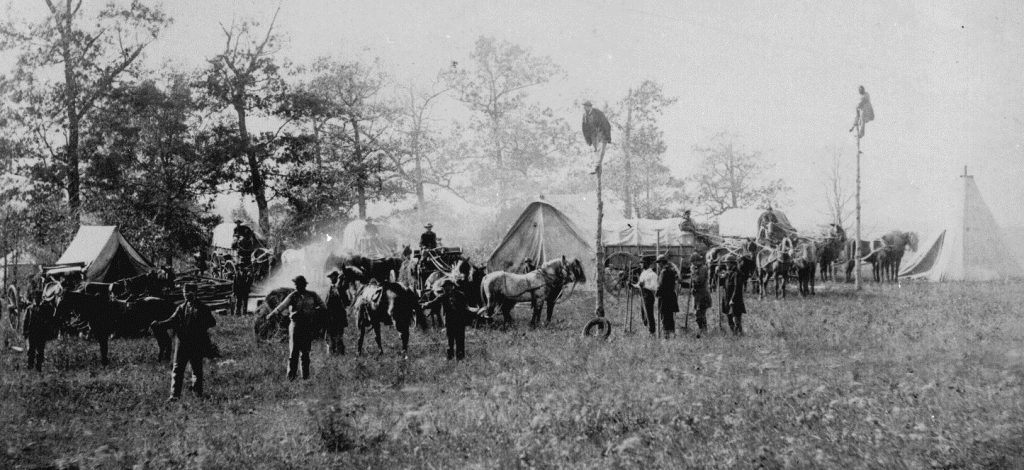

Horse-drawn wagons, the big rigs of their day, supplied remote areas with food, raw materials, and other goods.

“In the halcyon days of (the town of) Folsom, it was not uncommon for 20 or 30 eight- or ten-mule teams to leave daily with freight destined over the mountains,” recalled Judge W.A. Anderson in the Sacramento Union, Dec. 10, 1911.

When the east and west coasts were connected by rail in 1860, the US enter the age of the locomotive.

Folsom Prison was the first in California to use locomotive headlight technology to illuminate the prison yard and perimeter. Since the prison wall had yet to be completed, the lights improved security and public safety.

“(Fifteen locomotive headlights) have been set in position along the wall of the canal. Some of them have been (placed on) the opposite bank, the roof of the prison building, and about the grounds. They are lit early in the evening, (providing) enough light to brighten the prison yard. (Before this), the prison grounds have been without much light,” reported the Sacramento Daily Union, Oct. 28, 1890.

One prison train operator held the position from 1890 until 1906.

“Edward O’Brien of Represa died Sunday morning, death coming rather unexpectedly. O’Brien held the position as locomotive engineer at Folsom Prison for about 16 years,” reported the Sacramento Union, Sept. 11, 1906. “He was a genial gentleman (with) many friends among the prison employees and in (town). A native of Tiperary, Ireland, (he was) 59 years old. He leaves no immediate relatives here.”

Lighting the way

The first report of the newly created State Board of Prison Directors, dated Nov. 1, 1880, uncovered areas in need of improvement, including lighting.

“One of the first subjects that demanded attention was the better lighting of the prison yard and grounds. The light produced by lamps (were) inadequate as well as unsafe, troublesome and expensive,” according to the report. “The Board, after (considering) manufacturing illuminating gas, entered into a written contract with the San Rafael Gas Company. (They will) supply coal gas for the prison, for 10 years, at the rate of $3 per 1,000 cubic feet.”

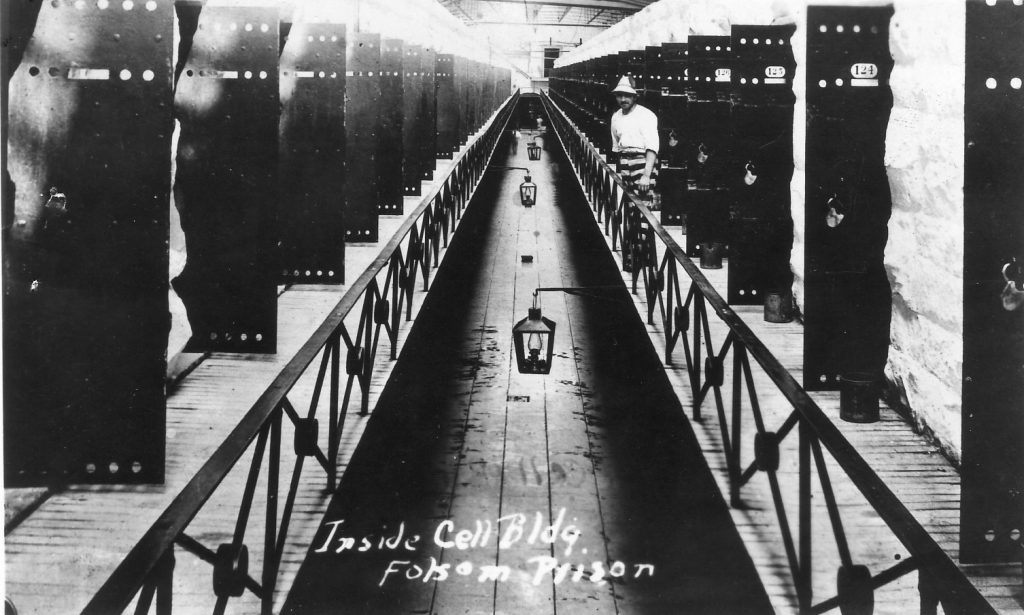

Cell interiors remained with the original lighting method of kerosene lamps. It took another 40 years for a new lighting system to reach the cells.

In 1893, Folsom Prison became the first prison in the nation to use electric lights.

“All of the old cell buildings have been wired for electricity. Recently the coal oil (kerosene) lamp method of lighting, which has been in vogue since the 1850s, gave way to (electric lights),” according to the 1917 prison directors report.

Crime also adapts to new technology

Like scam artists using cell phones and computers to bilk victims out of hard-earned cash, early swindlers used telegraphs and telephones.

“Lee Rial, said to be head of a bunco trust which fleeced (victims) by fake race horses, will appear before Judge Finlayson Friday. If (his appeal for a new trial is) denied, he will be sentenced. A jury found Rial guilty of grand larceny in obtaining $5,140 from G. P. Friesz in a Venice dummy poolroom,” reported the Los Angeles Herald, May 20, 1913.

Rial was sentenced to 10 years in San Quentin. Partner James Byrnes, originally sentenced to a decade at San Quentin, was instead sent to Folsom.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.