By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Office of Public and Employee Communications

After decades of working in law enforcement, Charles Aull returned to state service, first at San Quentin and then at Folsom Prison. This is the second-part of a two-part series on the lifelong lawman. (Read part one).

Getting back to prison work

In November 1883, he was appointed Deputy Warden at San Quentin, where he stayed for another four years. Some of the bandits he helped track down were serving time at the same prison. His friend and former boss, James Hume, was even married at San Quentin on April 28, 1884.

But it was his next assignment that truly tested his mettle. In 1887, after once again losing his post to a political appointment, he was chosen as warden of Folsom Prison. The new prison had been embroiled in controversy and the hope was Aull, with his reputation on the line, could clean up the situation. It turned out to be the post in which he served the longest.

“In this position, in the management of the prison and improvement of the grounds, he has shown a master hand and a clear executive head, especially in the control of the convicts who built the great dam across the American River, which will be used in connection with other works for the generation of electricity to supply the people of Sacramento with light and with motive power for machinery,” according to an 1895 biography.

In a letter to the 1890 National Conference of Charities and Corrections, Aull made the case for doing away with politics in the prison setting, especially when it affected employment.

“It is a safe estimate that 75 percent of (those who turn to crime do so) by the utter neglect of proper care and training in youth.”

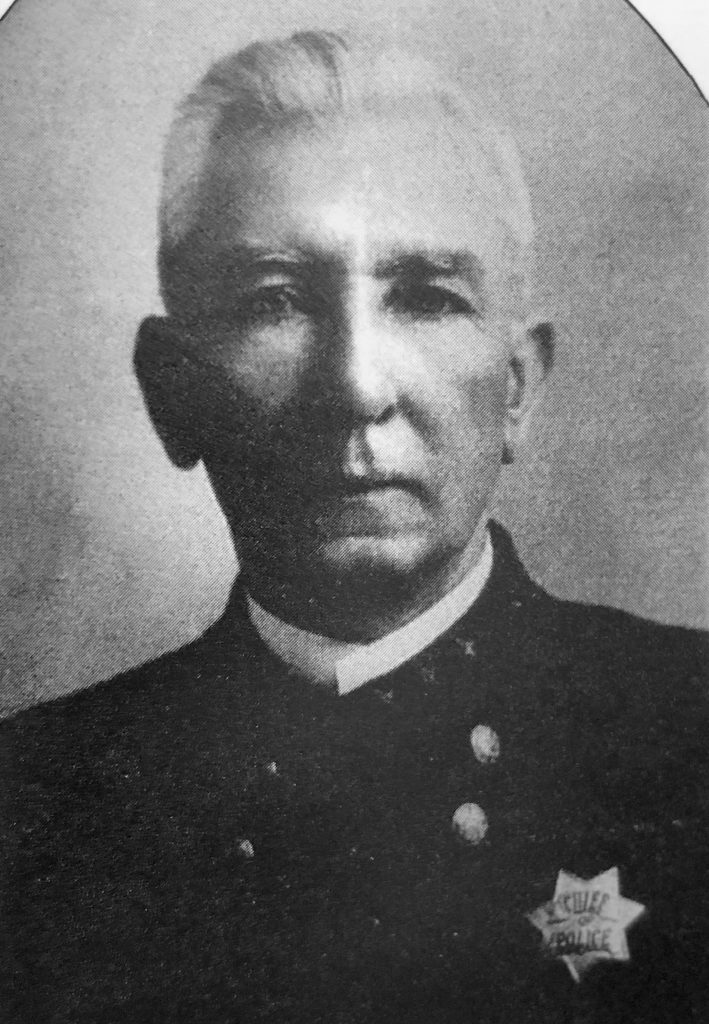

Folsom Prison Warden Charles Aull, 1887

“The most important (issue), in my judgment, is the selection of the officers and attaches of a prison. No statutory enactment, however stringent it may be, will avail anything, if it is to be carried into effect by an incompetent warden, surrounded by officers and guards that are forced upon him by political bosses. It is the personality of the warden that makes itself felt through every department of prison management,” Warden Aull wrote.

Aull claimed youth needed better care, education and opportunities to avoid becoming perpetrators of crime.

“It is a safe estimate that 75 percent of (those who turn to crime do so) by the utter neglect of proper care and training in youth,” he wrote in 1887, urging more apprenticeship programs for inmates as well as disadvantaged youth.

In the third biennial report of the state Bureau of Labor Statistic, dated 1887-88, it states, “State prison statistics prove that an overwhelming majority have not learned to employ themselves usefully in any particular occupation where skill or experience is required.”

According to statistics at the time, 808 inmates at San Quentin could read and write, 77 could read but not write and 335 were unable to read or write. Nearly half of the inmates had never learned a trade.

A chance at redemption

When prison directors inspected Folsom Prison in 1887, they found deplorable conditions for the men in the “dungeon.”

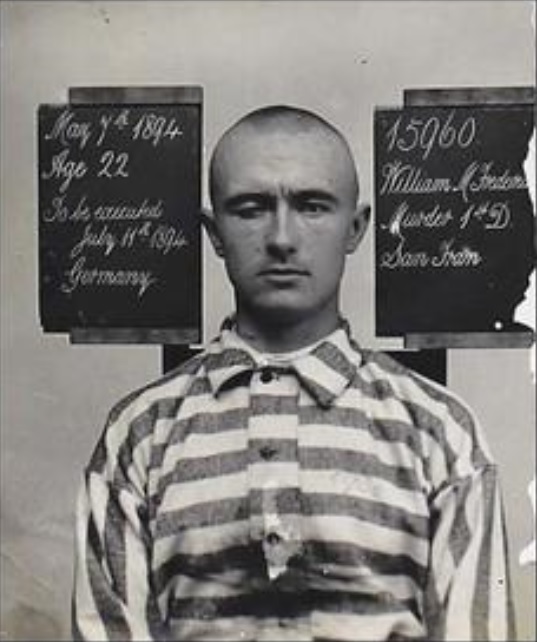

One such inmate was William Schmidt.

“I was sent from San Francisco to serve a term of 12 years for burglarizing a hotel on the San Bruno road on the ninth of January, 1885. I attempted to escape and was placed in solitary confinement. This was 18 months ago and ever since I have been in these dungeons. No lights were allowed me and I have lived in continual darkness ever since,” he told the San Francisco Examiner, July 23, 1887.

He said he was let out of his cell two weeks earlier, when the inmates were discovered by the prison directors. Schmidt attempted to escape multiple times and despite his claims, he had been offered opportunities to work his chosen profession as a mason. Unfortunately, his desire to flee overrode his work ethic. Each time he was outside for work, he attempted to escape, which eventually landed him in the incorrigible cells at Folsom.

The prison directors believed changes were needed at Folsom so Aull was selected as the new warden.

When Aull arrived at Folsom Prison, he immediately set about making changes. One of those changes included prison discipline. While still bound by orders from the State Board of Prison Directors, he also had some leeway.

On April 1, 1888, he removed Schmidt from solitary confinement and put him back on masonry work.

“First, inside the prison laying stone. He did well from the beginning. About the first of May we began work on a large masonry dam and canal on the American river outside the walls. We worked 300 convicts all last summer. Schmidt was placed on the work the middle of May and has not lost a day since,” Warden Aull wrote to the editor of the “Journal of Prison Discipline” for 1889. “The engineer in charge of the work says he has never seen a man perform so much work daily as Schmidt, in prison or out.”

Before releasing him from solitary, Schmidt was summoned to Warden Aull’s office.

“I talked to him for some time. I repeated to him all the violations of prison rules he was charged with, all of which he acknowledged. I found that he had abandoned all hope of ever attaining freedom. After getting all the details of his past life, I said to him that undoubtedly he had been a very bad and unruly prisoner, and that he had been severely punished. … I intended to give him a fair trial; that if he did well, he should be credited with it in due course of time. I also reminded him that his story was (well known) and there would be many obstacles in the way to lead him into trouble. Other convicts would seek to draw him into difficulties and would report him from time to time to gain favor with the officers. In a word, I warned him fully of all the difficulties he would encounter and assured him I would give the matter my personal attention and if he was not at fault, I would protect him. …. Before I finished talking to him he was visibly affected and tears came into his eyes.,” he wrote.

Schmidt, inmate no. 999, “was quietly pursuing the even tenor of his way, laying stone on the great dam at the Folsom Prison, (unaware) that his career was attracting the attention of philanthropists, prison wardens and penologists throughout the United States,” reported the San Francisco Examiner, July 5, 1889.

Despite repeated attempts by members of the public and media to gain access to Schmidt, Warden Aull would not allow it. He said since the inmate was doing so well, he didn’t want to disrupt him in any way.

“I was well aware of the responsibility I was assuming. His case had become a national one. If any serious consequences had resulted, my reputation as a prison officer would have been ruined forever,” Warden Aull wrote.

Tragedy strikes work crew

As the inmate masonry crew adjusted a large derrick, one of the guy wires broke from the fastenings May 18, 1889. The derrick, used for moving large stones and granite, began coming down.

William Schmidt, the crew foreman, yelled to others to get out of the way.

“(He) gave timely warning to all his fellow workmen. Watching the tall mast as it came, he (moved aside) so that it would miss him, but there was one thing that he overlooked. Three large guy (wires) were stretched across the river, which sagged as the mast fell. As the (wires) reached the water they were caught in the rapid current, swollen by melting snow, and the mast of the derrick was instantly swerved several feet out of the line it was falling,” reported the San Francisco Examiner, July 5, 1889. “Schmidt saw the danger too late. He was caught by the huge mast across the shoulders and neck, killing him instantly.”

Prison officials credited him with saving many lives that day.

The next day, “a large delegation of his convict friends asked permission of the warden to follow the body to the grave and conduct a funeral service over the remains. … The warden readily granted it, limiting the number to 30. The coffin, covered by a white sheet and literally covered with flowers in various designs, was placed in an express wagon and as the 30 privileged ones followed the improvised hearse, .. a guard force of two men followed, in position to prevent escapes. … The burial service of the Episcopal Church was read by ‘Dick’ Fellows, the noted stage robber.”

According to the newspaper, “nearly all the officers of the prison, including the warden, were present at the funeral service.”

Aull was not a paper pusher

Warden Aull had spent decades working the prison yard, capturing fugitives and solving crimes. It’s no wonder he was more hands on than most previous wardens.

In 1893, a desperate escape attempt at the prison ended in a gunfight. Rather than run from the trouble, Aull grabbed his Winchester rifle, 50 rounds of ammunition and rode into the fray.

The attempt was well planned and coordinated. When Lt. Frank Briare noticed a few inmates loafing about at the quarry, rather than working their job assignments, he approached them. One of the inmates came from behind and put a pistol to Briare’s head.

They forced Briare to walk up the hill. Other prison staff drew weapons, aimed at the small gang of inmates, but didn’t fire.

“Up to this time the guards had been unable to shoot as Briare was in the grasp of the would-be escapees and as they were closely banded together, a shot might mean death to (the hostage),” reported the Morning Tribune, June 28, 1893. “Just before reaching the summit of the hill, Briare jerked away.”

The lieutenant flung himself over the cliff’s edge, taking gun-toting inmate Smith with him. Inmate Frank Wilson was also knocked into the quarry during Briare’s scuffle. The prison staff opened fire “from all directions,” the newspaper reported.

“The (five remaining) convicts took to the rocks and concealed themselves as best they could and returned the fire as rapidly as possible.

“(Inmates) George Sontag, Russell Williams, Ben Wilson, Charley Abbott, and Dalton (remained) on top of the cliff. Guards Prigmore, Fitch, and Ayres then opened fire on the convicts, which was supplemented by Guards Taylor and Payne from across the river,” the newspaper reported.

Capt. Murphy, who had been nearby, rushed to the area, climbed the hill and took another gun from one of the guards. He also opened fire.

Meanwhile, in his office, Warden Aull “secured his own Winchester and cartridges, and (headed) to the scene of the conflict, which has assumed the proportions of a battle. When the warden reached the upper side of the hill, he sent for extra guards, in the meantime joining in the fight with Guard Fitch. The bandits were finally corralled in a hole behind a pile of boulders.”

When the warden had all men in place, he ordered them to fire at the same time into the same location in the boulders.

“In the space of a minute a perfect storm of lead was rained on this particular spot. When the firing ceased, Sontag crawled out in the open, more dead than alive, followed by Abbott, neither of whom could walk. The warden and Capt. Murphy and several guards advanced toward them.”

Sontag, though alive, had been shot three times in the leg. Abbott’s leg was broken and he’d been hit in two other places. In the hole they found two Winchester rifles, two pistols and a dirk.

Out of the 50 rounds Aull brought with him to the gunfight, 45 were fired, according to news account.

The incident also prompted faster completion of the wall around Folsom Prison.

“A 24-foot wall around the prison grounds, including the quarries, would eliminate all chance of a recurrence of a similar break as that of June 27, 1893,” according to the report of the prison directors dated 1894.

Aull’s detective skills pay off

Later, Warden Aull revealed he had been aware of the plan by notorious train robbers Christopher Evans and John Sontag to free their partner George Sontag from Folsom Prison by force.

To help prepare for the coming fight, Aull hired Joseph Prigmore, “a man in whom the warden has great confidence” from Humboldt County and assigned him to the post over the quarry.

Aull also hired “several picked men from (across) the state (who were then) placed in responsible positions. New guns and pistols were distributed,” reported the San Francisco Call, June 28, 1893. “So quietly was this done that neither guards nor convicts suspected anything unusual was about to happen.”

It was later learned a previously released convict, William Fredericks, returned to the prison and hid the weapons near the quarry.

“Wm. Fredericks, a convict discharged from (Folsom) May 26, 1893, had returned during the night and deposited two Winchester rifles, two pistols and some knives, in the quarry, on the line of the canal above the powerhouse. This was in pursuance of an agreement (made) before Fredericks’ discharge from prison,” according to the Appendix to the Journals of the Senate and Assembly, 1894.

The Sontag Brothers

George Sontag, aka George Conant, had been convicted of train robbing in 1892. His brother and Christopher Evans managed to get away, helped plan George’s escape, but were themselves tracked down.

John Sontag was shot and killed in June 1893 in Fresno. Evans was badly wounded, losing an eye and an arm in the gun battle. Evans was sent to Folsom Prison. He was paroled in 1911 but only on the condition that he leave the state. He died in 1917 while residing in Oregon.

George Sontag continued serving his sentence. He was paroled in 1909, wrote an autobiography called “A Pardoned Lifer,” and lectured on the dangers of living outside the law.

Fredericks wasn’t out for long. He was arrested after killing a bank teller during a robbery, sent to San Quentin in 1894 and was executed in 1895.

Rehabilitative offerings

Aull was ahead of his time in many respects, including his innovative plans to teach the inmates skills they could use outside the prison walls. Some of those skills simply included interacting with other people in social settings.

He organized baseball games for the inmates and festivities around the Fourth of July. His methods were seen as soft but Aull stood by the notion that punishment alone would only make hardened criminals while adding softer methods could prevent conflict inside and outside the walls.

Wife’s death devastates Aull

In 1897, Aull lost his wife. From that point on, “a change was noted in his health,” according to news accounts at the time. A year later, he was in San Francisco seeking treatment for a kidney ailment. He returned to his post periodically between medical appointments.

On Oct. 9, 1899, the longtime lawman died at just 50 years old.

“After a long illness of varying intensity, Charles Aull, Warden of the State Prison at Folsom, passed away yesterday,” reported the Sacramento Daily Union, Oct. 10, 1899. “The attack which laid low the distinguished prison manager came a week ago … though his health had been precarious a long time.”