From Black Bart to Rattlesnake Dick, bandits who plundered stagecoach routes in California were eventually forced to trade in their six-guns for room-and-board in one of the state’s two penitentiaries: San Quentin or Folsom Prison.

This is the story of the choices made by those wearing a badge and the stagecoach robbers fleeing the law.

Rattlesnake Dick, Tom Bell and Black Bart

Tom Bell, aka Thomas Hodges, and Richard Barter served time at San Quentin in the mid-1850s. Bell escaped and reunited with Barter after his release. Barter was better known as Rattlesnake Dick. Both met their fates at the hands of others. Bell was killed by a posse near Firebaugh while Barter was killed in a gunfight with a posse near Auburn. (Read their story.)

Charles Boles made his way west and became one of the most famous stage robbers in history. Going by Black Bart, it’s estimated he robbed 28 stagecoaches between 1877 and 1883. Also known as the Poet of the Sierra or the Gentleman Bandit, Boles was noted for being polite and never firing a shot. Detectives managed to track him down to San Francisco. He was sent to San Quentin where he learned pharmacy skills and vowed never to return to prison. His trail runs cold after he was paroled. (Read Black Bart’s story.)

Dick Fellows and Charles Dorsey

Legendary stagecoach bandit Dick Fellows was in an out of prison. Unfortunately for Fellows, his reputation far exceeded his criminal exploits. Fellows successfully robbed numerous stagecoaches before he was caught in 1870 and sent to San Quentin. He volunteered to work in the library and teach Sunday school. In 1874, he was released but was back to the stick-up game by 1875. Fellows broke his leg while fleeing but still managed to get away with $1,800. He was caught and again landed in San Quentin.

He feverishly wrote letters advocating for his pardon, pledging to stop his criminal ways. Again he took part in religious services and worked in the library. In 1881, he was released but wasn’t out long before he held-up another stagecoach. He was caught and sent to Folsom Prison in 1882. When an inmate was killed in an 1889 accident at the quarry, Fellows requested a funeral service for the man. He was pardoned by the governor in 1908, having spent nearly 40 years of his life in prison. According to many later reports, he changed his name and was living in another state teaching Sunday school and writing for magazines.

Charley Dorsey robbed a stage in 1879 in Nevada City and a banker lost his life during the hold-up. Dorsey was sentenced to life in prison in San Quentin. He was received in 1883. During a 1911 newspaper visit to the prison, he was one of three inmates prominently mentioned. Shortly after the play “Jimmy Valentine” was performed in the prison, Dorsey was paroled.

Law man Charles Aull

Charles Aull was a longtime law man. He was Stanislaus County undersheriff in 1872 and was appointed to the San Quentin turnkey post in 1875. He began tracking down stagecoach bandits with legendary Wells Fargo Detective James Hume in 1881. One of those on his list included recently paroled bandit Dick Fellows who was eventually caught and sent to Folsom Prison. In 1883, after helping track down stage robber Bill Miner and others, Aull went back to work at San Quentin. In 1887, he was appointed warden of Folsom Prison, overseeing some of those stage bandits he helped put there. He also helped thwart an escape attempt organized by the Sontag and Evans gang (see below). Aull passed away in 1899 at just 50 years old. (Read his two-part story.)

Who were the Sontag & Evans gang?

The notorious Sontag and Evans gang played a prominent role in an attempted break-out at Folsom Prison. The Sontag Brothers, George and John, had a criminal career going back to their teen years. George even served time in the Nebraska State Prison on embezzlement charges.

John arrived in Los Angeles in 1878, becoming a brakeman for the Southern Pacific Railroad. A work-related injury sidelined his new career. He believed he’d been unfairly treated by his employer after the injury, souring his opinion of the railroad company.

As the railroads began claiming fertile land, Chris Evans believed his farm was threatened. With an ax to grind, he found an eager accomplice in John Sontag.

Goshen hold-up nets $600

On Jan. 21, 1889, Sontag and Evans boarded the train near Goshen, put on masks, “climbed over the tender, ordered the engineer to stop and proceeded to the express car (where they stole) about $600,” according to “Celebrated Criminal Cases of America” by Thomas S. Duke.

After their first success, they boarded a train at Pixley on Feb. 22, followed the same plan, and got away with $5,000.

Two years later, Sontag and Evans hit a train in Ceres, this time using dynamite. Unfortunately for them, Detective Len Harris was on board the train. He jumped out, surprised the bandits, and fired a few shots. Sontag and Evans fled, empty handed.

On Nov. 5, 1891, a frustrated John recruited his brother to target a train in Minnesota. George had become more of a home body and family man, farming and ranching. He sent his family to a neighboring city, just in case. The brothers headed to the station, where they waited until the train stopped. The Sontags slipped on board and hid until the train got underway. They followed the same plan and got away with $9,800.

Gang keeps going; runs afoul of the law

In 1892, George planned another hold-up, this time with Evans, while John waited in California. When George got inside the express car, he couldn’t find the cash so they ended up without any loot.

The three assembled in Fresno where George, who appeared to have become the brains of the operation, planned another hold-up. George and Evans hit a train traveling between Los Angeles and San Francisco while John waited with their getaway horse-and-buggy. They grabbed three bags of money but only one of them was in American currency, worth $500. This time, George’s questions and planning in Fresno seemed suspicious, and the horses were recognized as belonging to Chris Evans.

Following up on this information, the deputy sheriff and a railroad detective paid a visit to the Evans farm.

John and Evans caught them by surprise. Evans shot the deputy, “inflicting a serious wound, and when (the deputy) fell, Evans came up to him and held a pistol (to his head) but did not fire.” The victim pleaded for a few minutes more of life, saying he knew he was a goner. Evans gave him that time.

“Sontag fired at (Detective) Smith” but missed.

On the run for a month

Sontag and Evans eluded law enforcement for about a month, during which time they killed posse member Oscar Beaver. On Sept. 13, 1892, another posse approached a cabin, not knowing the men were inside. Evans and Sontag opened fire, killing two men and severely wounding a third. Again, the men escaped.

Meanwhile, George Sontag had been arrested and was put on trial for the train robbery. He was given life in prison at Folsom.

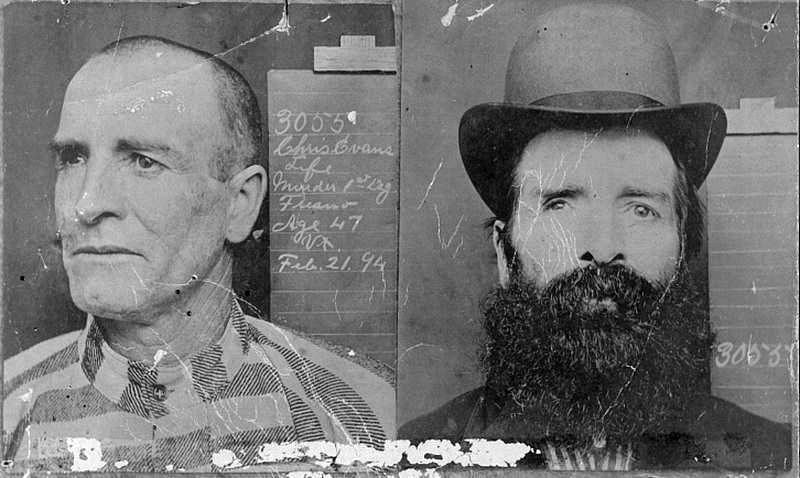

There was another shootout with Sontag and Evans on June 11, 1893. The pair escaped, but this time both had been wounded. The next morning, John was found dying near a hay bale. On June 13, Chris Evans surrendered, having lost an eye and an arm in the gunfight.

Back at the prison, George Sontag was plotting his escape (read about the attempt). George was eventually pardoned in 1908 and began writing about the importance of avoiding crime. Evans paroled in 1911 and moved to Oregon, where he died in 1917.

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.