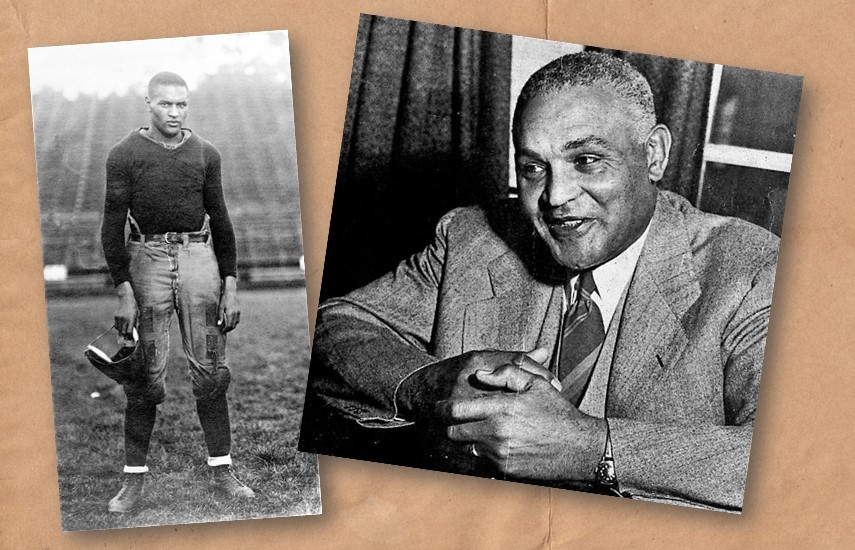

Lawyer served on parole board, headed Adult Authority

While working to earn his law degree, Walter Gordon became Berkeley’s first African American police officer. He later went on to serve on the Board of Prison Terms, followed by becoming chairman of the newly created California Adult Authority.

The grandson of Georgia slaves became “Berkeley’s genial favorite son (who never) swerved from his professional philosophy of integrity, loyalty to duty, efficiency and courtesy,” one reporter wrote in 1957.

His accomplishments came during a time of racial segregation and civil unrest, paving the way for those who followed. According to 1940s-era San Quentin Warden Clinton T. Duffy, Gordon recommended an African American man for a guard post. Swayed by Gordon, as well as the candidate’s abilities, the man was hired.

According to the UC Berkeley Alumni Association, Gordon was “a man of many firsts: the first All-American in football at Cal, first African American All-American on the West Coast, first African American to graduate from Berkeley Law, and first African American police officer in Berkeley.”

Playing college football was difficult, but Gordon excelled.

“Although he was a star player for the Golden Bears, the laws that called for segregation did not make it easy for Gordon to travel with his team, as he was not allowed to stay at the same accommodations as his teammates,” according to the association.

In 1918, he earned his Bachelor of Arts degree and took on the job of assistant college football coach. In addition to playing for the college, he also went on to play for the Student Army Training Corps.

First African American Berkeley police officer

“He had attained the rank of sergeant in the Student Army Training Corps,” reported Opportunity magazine in their September 1932 edition. “At the end of the war, he was out of school, working here and there at anything that he could find. One day, in July 1919, he was passing by the Elks Club in Berkeley. The voice of a man coming out of the club greeted him. It was Police Chief August Vollmer. ‘How’d you like to join the police force?’ he asked.”

Gordon’s introduction to the department wasn’t smooth. He faced complaints from the neighborhood and fellow officers. “To Chief Vollmer’s credit it can be said that he was entirely immune from color-phobia,” the magazine reported.

“When Gordon was placed in a largely white neighborhood, and there was pushback, (he) offered to move or quit the police force. Vollmer would hear nothing of it,” according to author Willard Oliver, a professor of criminal justice at Sam Houston State University in Texas.

Some officers also objected to working alongside an African American.

“When some officers came to Vollmer’s office to tell him either Gordon went or they did, Vollmer said he was sorry to hear that; they could leave their badges and guns by the door on the way out,” Oliver told UC Berkeley News in 2017 (read their story).

Gordon changed attitudes

By the time he left the force on Jan. 1, 1930, the views of his fellow officers and those of the neighborhoods he served had shifted. Residents said they regretted his departure. Officers presented him with an engraved fountain pen set, acknowledging his dedication.

While serving as a police officer and assistant coach for the University of California, he also attended law school.

Gordon served on the police force for 10 years. After earning his Juris Doctorate from Berkeley law school, he started practicing law.

According to the New York Times, he practiced law from 1922 until 1944 and led the Alameda County branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People for 14 years.

Gordon appointed to Board of Prison Terms

“In 1943, Gordon was appointed to the old State Board of Prison Terms and Paroles,” reported the Oakland Tribune.

A year later, during the department’s restructure under Gov. Earl Warren, the board became the California Adult Authority. Gordon continued serving, becoming the chairman in 1945.

“Recognizing the dignity and worth of fellow human beings is the governing principle in the policies and actions of the California Adult Authority in charge of the parole system for men in the state’s correctional institutions,” reported the Chico Enterprise, July 31, 1952. “The principle (was) outlined by Walter Gordon, chairman, and the four additional members of the board during their brief visit to Paradise (and) Magalia camp.”

Gordon shared a vision of compassion, forgiveness and second-chances.

“‘There is no ‘we’ and ‘they’ in our relationship,’ Gordon said. ‘We are all in this world together. There is no separate world for us, and for them, just because many of them have had one moment of emotional explosion in their lives,'” the Chico paper reported.

Appointed governor of US Virgin Islands

In August 1955, President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed Gordon to Governor of the Virgin Islands.

“Walter Gordon has handled his state position with great credit to himself and the two governors who placed their faith in him,” said Sen. Thomas Kuchel of California. “I am confident he will perform equally valuable service as governor of the Virgin Islands, a job which I understand requires the broad administrative experience and ability already demonstrated by Gordon. I was happy to have informed the President of my approval of his selection.”

He served in the post until 1958. The President then appointed him as a federal judge in the Virgin Islands, serving 10 years.

Gordon retired from the bench and returned to his home in California. He passed away at 81 in 1976.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.