News stories covering California Men’s Colony (CMC) staff, programs, and the incarcerated population help tell the institution’s history.

With the opening of CMC East Facility in 1961, everyday life at the prison was about to change. CMC West, established in 1954, housed older and infirm incarcerated people. The new facility would house younger men while also expanding rehabilitation opportunities.

The relationship between staff and the incarcerated was unique to CMC, with those in custody holding the keys to their cells.

Part of the culture difference at CMC could be attributed to its staff and lower custody level.

While a prison has walls, guard towers, yards, gates and bars, the real stories of a prison are best told by those who put on a uniform or those serving time.

CMC opened in 1954 (read the original story).

A story about fractured people

On Dec. 12, 1973, the San Luis Obispo Telegram-Tribune published the first of a four-part series examining life on the inside at CMC.

In 1973, starting pay for a correctional officer was $965 per month. There were 333 of them employed by CMC, according to newspaper articles.

“The Men’s Colony story is about men whose frayed pasts turned society against them. It’s also the story of lonely men rejected by family and friends; men trying to recoup; men whose sole hope is the day, once a year, when they go before the state parole board,” the newspaper reported. “Leroy Amos (has been) imprisoned for about 11 of his 24 years. His current stint for burglary began at the Men’s Colony in 1969. ‘I’ve been in trouble with the law since I was 9 years old,’ he said. ‘At 19 years old, (my 10-years-to-life sentence) scared the hell out of me.’”

Amos said he appreciated the younger correctional officers.

“The younger officers talk to (us and) treat us like human beings,” he told the newspaper.

Rehabilitation efforts in the 1970s

“The prison provides academic training through high school (or) vocational training such as electronics, sheet metal and carpentry,” the paper reported. “It is hard to detect the prison air in the vocational workshops, such as the drafting classrooms and machine shops. They are well-equipped and students are intensely at work on their projects. Instructors are on hand for advice.”

Odis Franklin Smith, a baker for 16 years in the state correctional system, previously worked at Soledad and Folsom. For three years, he served as CMC’s head baker.]

“The atmosphere is much easier and lighter here than at Folsom,” he told the newspaper. “I like working with people. The fact that they’re inmates makes no difference.”

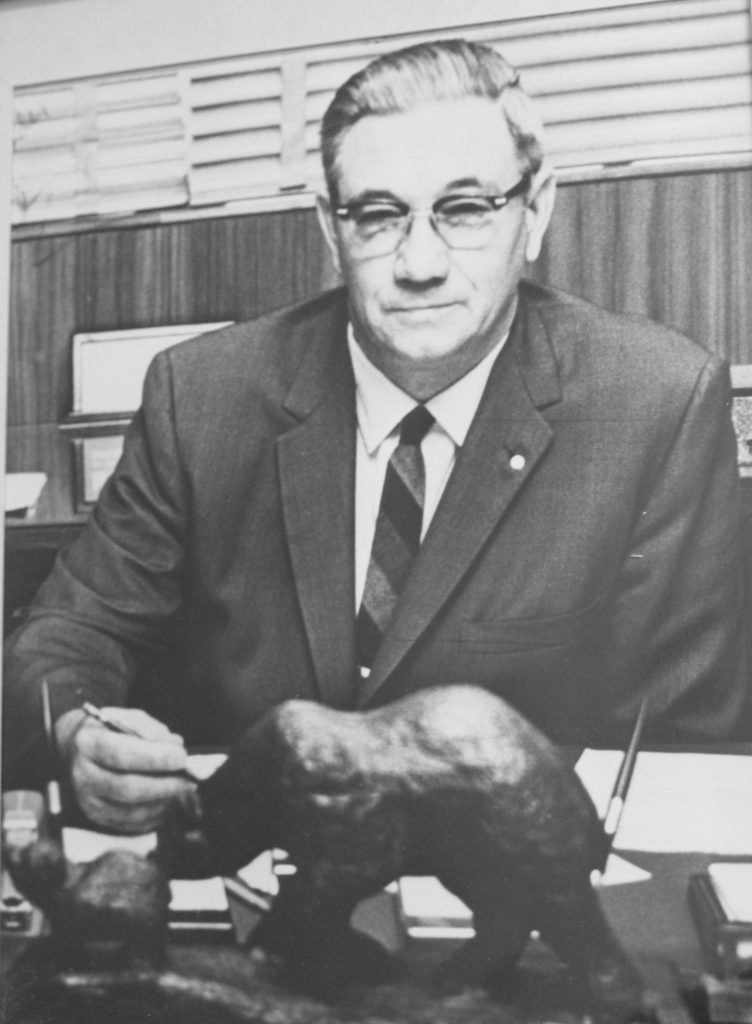

On Dec. 13, 1973, the paper interviewed Superintendent D.J. McCarthy.

“It’s a different work inside,” McCarthy said. He described most of those serving sentences at CMC as “honest John citizens paying for their mistakes.”

McCarthy began at San Quentin State Prison in 1949 as a correctional officer. He also worked 10 years at California Medical Facility in Vacaville and did various stints at headquarters in Sacramento.

Sentiments ring true even today

“Some people still insist that prisons should punish,” McCarthy said. “I don’t think this is the answer. Some men need only two months in prison while others need two years. But while punishing him, you also have to treat him. We can protect society now with fences and guns, but simply warehousing the men will not protect society in the long run.”

McCarthy said he enjoyed walking the prison yard “just to talk to people and get the feel of the climate.”

Steve Clark, a 25-year-old incarcerated person, was serving his first five-year prison sentence for armed robbery.

“All my life I’ve fought authority,” Clark told the newspaper. “The biggest adjustment to prison life was having people telling me when to get up, when to brush my teeth, when to eat – adapting to an authority that isn’t going to bend no matter what. At school, if you don’t conform, you flunk out. But you aren’t going to flunk out of this joint.”

He said he tried to keep a positive attitude.

“I do my time one day at a time,” he said. “I don’t worry about tomorrow. Since I have to do the time, I might as well make it as comfortable as possible. It’s easier on me and on the prison staff.”

A day at CMC in 1973

The newspaper also described a typical day for those serving time at CMC.

Housed in individual cells, they rise at 6:30 a.m. Each cell is about six by nine feet, with a narrow bed taking nearly half the space. Each cell has a window facing either the quad yard or the outside.

Rules in place at the time:

- no wall hangings or paste-ups

- no visiting in the hallway

- cell doors closed at all times

- no visiting other buildings, game rooms or television rooms

- no card playing.

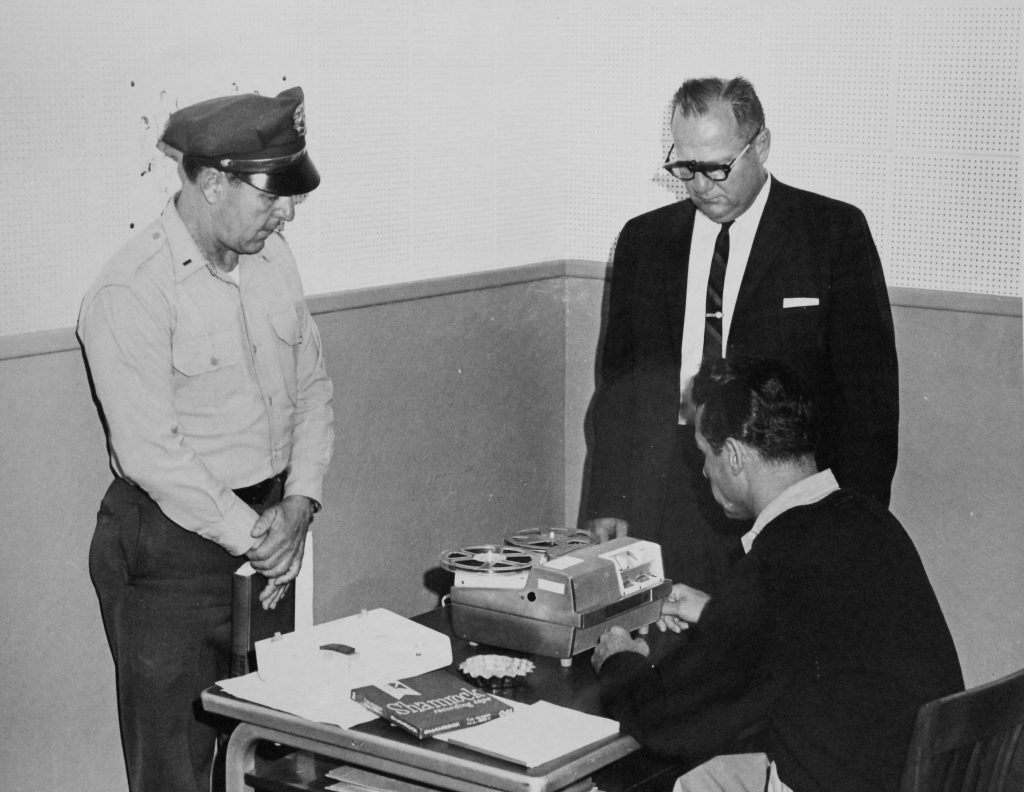

Each carries the key to his own cell. This privilege is unique in the state prison system. The only time their keys don’t work is during sleeping hours and during counts.

By 7 a.m., they are ready for breakfast, then most of them head off to work an eight-hour shift in one of the prison’s several industries or service occupations. This makes the prison almost self-contained.

After work, they are free until 10 p.m. for activities of their choice.

For every 50 incarcerated men, there is a television and game room. Outside the television room is a poster showing the evening’s viewing lineup, previously voted on by the population. Among the preferred programs were ‘Sanford and Son,’ ‘The Flip Wilson Show’ and the news.

CMC staff making a difference with incarcerated

On Dec. 14, 1973, the newspaper published a story about staff working in the prison.

“Capt. Norman Williams, in charge of prison security, said, ‘We are not armed. We walk into a building with 300 (incarcerated people); some of them with nothing to lose.’”

Williams described his job duties:

- help stop the flow of narcotics and weapons into the prison

- keep a close eye on employees who may become involved with trafficking

- separating population members who may harm each other

- aiding in the investigation and prosecution of crimes happening inside the prison.

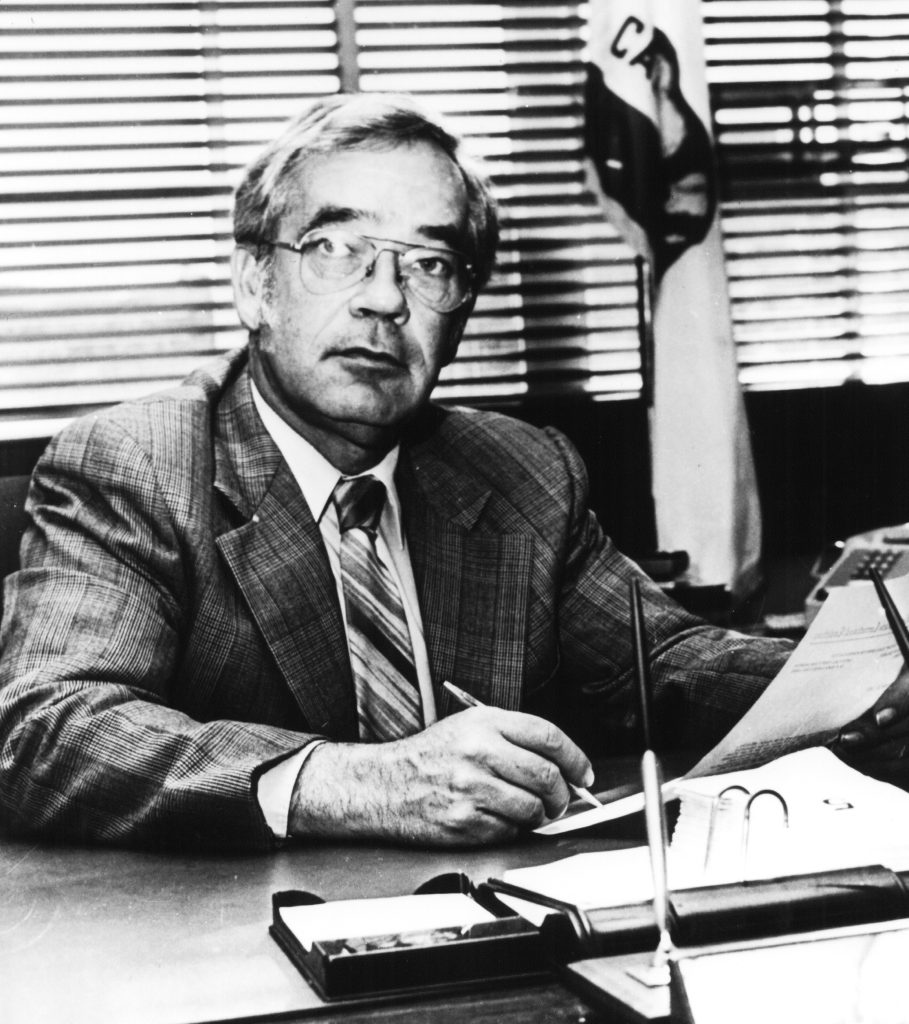

“The potential for danger is always there and you’re aware of it,” said program director Wayne Estelle, head administrator for one of four quads, 600 per quad. “You don’t let it interfere with how you conduct your business. If you do, you better take another look at the job.”

Estelle, 40, began his career as a correctional officer at Folsom State Prison in 1959. He went to CMC in 1961, left a few years later to work as a parole hearing officer in Sacramento and returned to CMC in 1971 as a program administrator.

Correctional work was his family’s calling: Estelle’s father worked for the department until his death in 1957. Meanwhile, Estelle’s brother worked at Folsom State Prison and then became the director of the Texas Department of Corrections. Estelle would go on to become CMC warden, serving from Nov. 1, 1983, to Sept. 30, 1991.

Education behind the walls

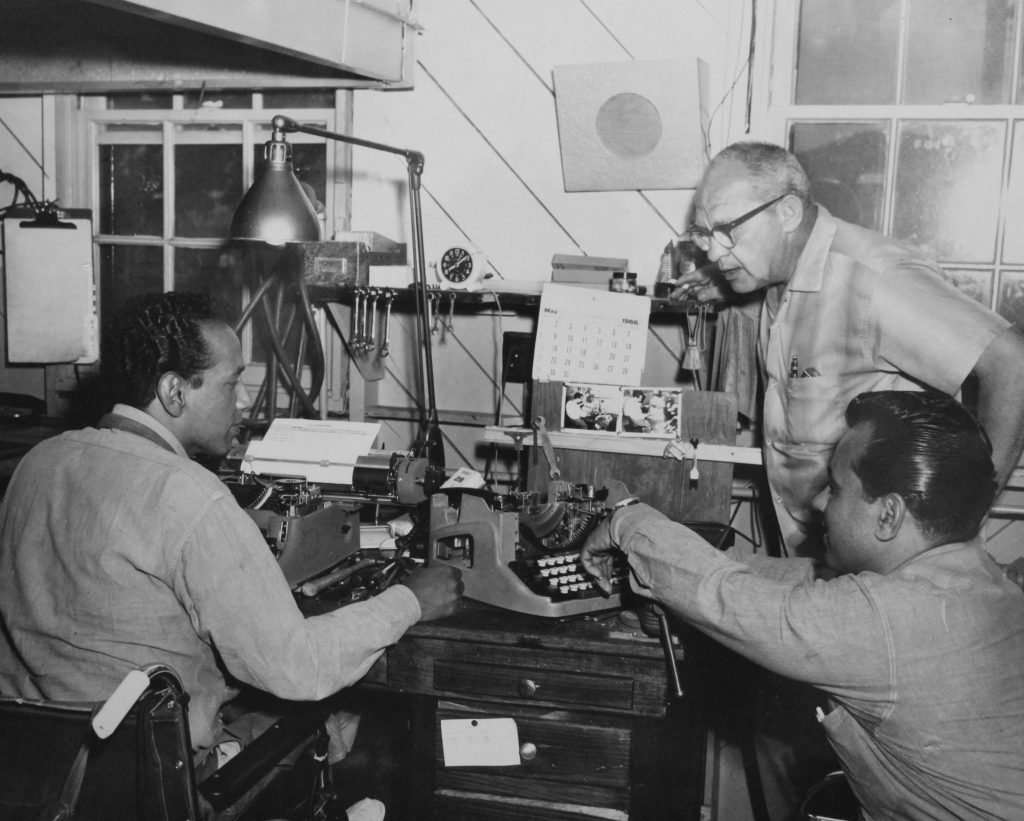

Today, correctional instructors work to rehabilitate their students through education. It’s not a new concept. In the 1970s, the population were learning job skills to make it in the outside world.

The Telegram-Tribune, April 19, 1974, published a feature story on CMC instructors.

“About a third of the 2,400 prisoners at the colony attend classes either half or full time. Some are finishing up their high school educations, (while) others are learning to read and write for the first time,” the newspaper reported. “An educational program for CMC inmates is ‘highly desirable,’ said James Knadler, the administrative liaison between the Men’s Colony and the San Luis Coastal School District, since ‘lack of education is part of the problem.’”

He said it was an eye-opener to find out how many of the prison’s population read at the first- and second-grade levels.

Education is a way to help break the cycle of criminal thinking.

“Most come through poverty,” said Bruce L. Russell, CMC supervisor of education. “They have to get that feeling of being worthwhile. I know we’re going to have failures, but the successes are sweet.”

Russell said 17 instructors teaching at CMC are “a combination of classroom teacher (and) psychologist.”

Principal of the academic section in 1974 was John Bjarnason.

He said teachers have to gear their material to the adult interest level while making it simple enough for beginning readers.

Superintendents/Wardens from 1954 to 2011

- John Klinger, July 1, 1954-June 30, 1966

- Harold Field, July 1, 1966-July 31, 1971

- Daniel McCarthy, Aug. 1, 1971-Oct. 31, 1983

- Wayne Estelle, Nov. 1, 1983-Sept. 30, 1991

- William Duncan, Dec. 1991-April 11, 2002

- John Marshall, Oct. 30, 2003-March 21, 2010

- Terri Gonzalez, March 22, 2010-Nov. 20, 2011 (first female to lead the prison)

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.

Related content

Echoes from the Past: Restoring history’s missing pages

While researching stories for the Unlocking History series, we often find damaged documents, missing photos, or incomplete information. One example…