(Editor’s note: This story, exploring the history of California Men’s Colony, was originally published in July 2016.)

History shows California Men’s Colony was an experiment in penology, creating a place to incarcerate older men by using a former military hospital.

When it opened in 1954, California Men’s Colony continued the tradition of repurposing former military facilities into state conservations camps, hospitals and prisons.

Other examples include:

- Pine Grove Youth Conservation Camp (1945)

- Deuel Vocational Institution (1946 at War Eagle Field in Lancaster before moving to Tracy)

- and California Medical Facility (1950 at Terminal Island before moving to Vacaville).

When the state needed a place for older and disabled incarcerated people, they turned to a vacant National Guard hospital and camp at San Luis Obispo.

History of California Men’s Colony originally dates to 1920s

The camp’s roots date back to 1928 when it was established as a military training camp.

“The new state National Guard camp at San Luis Obispo will soon be large enough to accommodate 2,200 troops,” reported the Healdsburg Tribune, Dec. 6, 1928.

During the ramp-up to World War II, the National Guard greatly expanded Camp San Luis Obispo.

“Scores of pieces of heavy construction equipment, more than was used in the building of the Boulder Dam, are at work at Camp San Luis Obispo. Thousands of workmen are building the full-division camp (for) the 40th Division of the National Guard,” reported the Lodi News-Sentinel, Feb. 26, 1941. “The 500 buildings going up include warehouses, administrative and mess buildings. The hospital will have 62 structures (with) 1,000 beds.”

Seven years later, the state began liquidating those buildings.

The Dec. 6, 1948, edition of the Madera Tribune reported on the sale.

“The State Department of Finance is handling the sale at Camp San Luis Obispo. Buildings (are) priced from $38 to $48,” the paper reported. “The buildings are 16 by 16 feet in size. (They are) complete with door, five windows, and tongue-and-groove flooring. Many are equipped with heating stoves.”

Ready for incarcerated

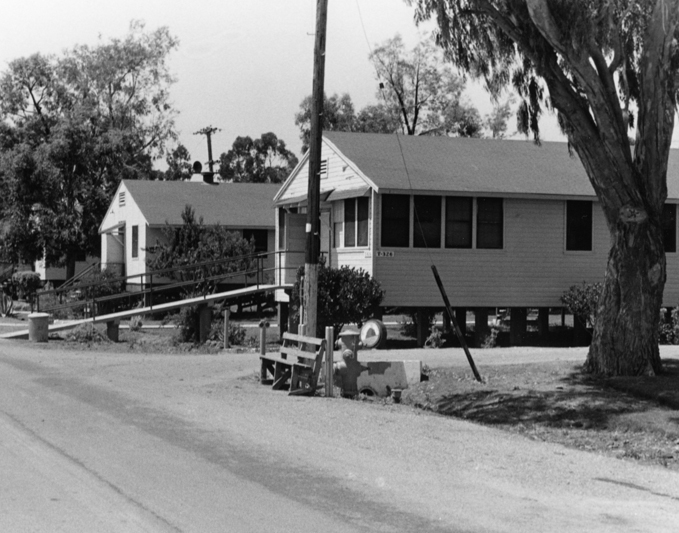

The hospital section of Camp San Luis Obispo was selected as the site of California Men’s Colony.

“In late 1954, a busload of 50 (men) arrived from Folsom Prison. (They were) specifically selected for skills in carpentry, plumbing and other construction trades. (They) remodeled 59 buildings in what became known as West Facility,” according to Correction News, November/December 2001. “A month later, West Facility was ready for occupancy.”

Former military barracks were used

The original facility used the old military barracks to house inmates and there was no fence, but one was added years later.

A 1958 report to the Governor’s Council, submitted by first CMC Superintendent John H. Klinger, described the facility and its mission.

“(CMC) opened in July 1954 in temporary quarters in the hospital section of Camp San Luis Obispo,” the report states. “The new institution, the eighth in the California prison system, was activated (as) an additional medium-security prison. The (incarcerated) population is 1,250. About half the men are infirm due to advanced age, chronic ailments or disabilities. The other half, who are sound physically and mentally, work (to keep the institution running). They are selected at other institutions because of their ability to perform the duties required. (They are also) considered suitable for the type of (custody) provided here.”

California Men’s Colony by the numbers

According to the report, “This former hospital facility has been adapted to serve the needs of CMC quite well. Required facilities which were lacking are being added. In 1954, there were approximately 60 Army barracks buildings, encompassing 238,435 square feet, used in the program of the Men’s Colony. A year later, 20 additional buildings had been added, providing an additional 78,404 square feet. When the work now in progress is completed, the physical plant of the Men’s Colony will include about 100 buildings that have either been activated where they were located, or moved in, remodeled and placed in use. The institution will have approximately 375,814 square feet of building space by the latter part of this year.”

Elderly and disabled at CMC West

The median age of incarcerated men at the time was 54.4 years.

“The primary purposes of the institution are: To provide a specialized institution for the elderly, infirm and disabled offenders in a physical and custodial setting apart from the most secure and expensive restraint necessary for younger offenders; to relieve overcrowding at other institutions; to provide a program especially designed for the retraining, rehabilitation and replacement in civilian life of the elderly and infirm offender; to develop a research program into problems of the aging that will not only aid those in prison but also benefit the rapidly increasing group of elderly persons in the general population,” the report states.

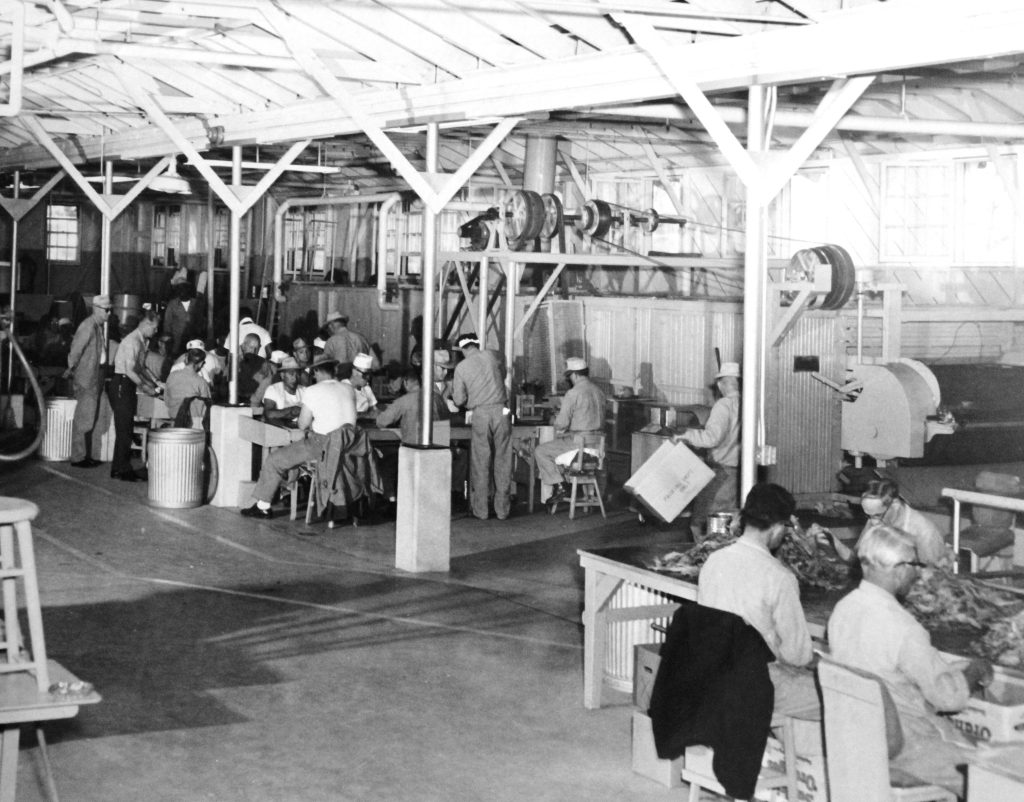

Tobacco factory moves to CMC

According to the 1958 report, “In June, the first correctional industry assigned to this institution will be in operation. This is the tobacco factory that has been moved from San Quentin to the Men’s Colony to assist in providing employment for a part of our population. It is anticipated that once in operation, this activity will employ from 50 to 70 men with production per man even more efficient than heretofore, the reason being that having an older population from which to recruit help, these men are more interested in their jobs, are more stable in their thinking and are more interested in keeping busy on some type of constructive work.”

(Note: The factory was later closed and today tobacco in a state prison is considered contraband.)

Groundbreaking methods used at CMC

The 1958 report touted CMC as groundbreaking in its methods, concept and design.

“Nearly four years of experience with the elderly, infirm and handicapped offenders in an open-type minimum security facility has demonstrated the practicality of this new kind of correctional institution,” Superintendent Klinger wrote. “The value of modified custodial methods for improved institutional morale and the development of special release preparation have been proven. Although a 12-foot fence surrounds the main group of buildings, there are no guard towers.”

(Note: Today, there are towers and fences around CMC West.)

The report also pointed to the rehabilitative success of programs at CMC.

“Release planning for (the incarcerated), in many cases, includes specialized placement in boarding homes and other facilities for elderly persons,” the report states. “The inmates have their own Alcoholics Anonymous chapter which meets twice monthly, usually with visitors present from outside AA chapters. Inmates are being returned to society with greater potential as integrated family members, workers, citizens and taxpayers. All inmates are seen by the superintendent at the time of departure from the institution. Almost without exception, they have expressed their appreciation for the considerate treatment they have received.”

Group counseling

According to the report, CMC also implemented group counseling with 800 inmates participating. CMC even invited social service agencies into the prison.

“Every effort is made to take advantage of the many resources available to older people,” the report states, listing federal, state and county agencies as well as non-profit groups who regularly visited with the inmates.

According to an April 11, 1968, Los Angeles Times article, the inmates sent to CMC were the “country gentlemen of the convict crowd.”

“As far we as know,” explained Superintendent Harold V. Field, “this is the only prison for old men in the nation.”

“If it were not for the 12-foot fence surrounding West Facility’s 43 acres, a visitor might imagine he were in a Palm Springs resort rather than on the grounds of a state prison,” the paper reported. “Men in their 50s, 60s, 70s and 80s, dressed in polo shirts and white shorts, played tennis, gray-haired fellows played on putting greens and handball courts, others played paddle tennis (and) shuffleboard.”

No cells at California Men’s Colony original facility

“Here we have no cells,” the superintendent told the newspaper. “Our residents live in 60 open dorms. We feel treatment is much more humane than any other prison in the country. These men are perhaps the best adjusted prisoners in the nation. At their ages, they do not have the overt hostilities of younger men. Arguments and fist fights often common among prisoners seldom occur here.”

A department official said the older incarcerated men appreciated CMC’s atmosphere.

“It worked out that older inmates loved that place,” said former department director Dan McCarthy. He also served as CMC’s chief deputy warden in the 1960s and later as its third warden, according to 2001 issue of Correction News. “There were no kids or gangbangers to deal with.”

New facility for younger incarcerated people

CDCR began to set its sights on a new facility for younger offenders. In 1961, CMC East Facility was scheduled to open with a complex of new buildings within a secure perimeter.

“CMC is now about to embark upon a new phase of its career. It is anticipated that the present (West) facility will continue to operate in temporary quarters for many years to come. However, on a separate site adjoining the present institution, permanent facilities for four 600-man units for younger offenders will be constructed. These four units are scheduled for occupancy in 1961,” states the 1958 report to the Governor’s Council. “Master planning calls for the eventual expansion of three permanent facilities into a colony-type institution of five 600-man units, separate for purposes of confinement, treatment and training but combined for purposes of general services and administration.”

The report offered advice for the future.

“Every effort will be made to transplant in the permanent institution the spirit of cooperation and goodwill that has characterized the relationship between employees and inmates in the temporary facility,” Superintendent Klinger wrote in 1958. “Any reduction in the traditional attitude of rejection that ordinarily exists between prison inmates and prison personnel will contribute to the success of the correctional process.”

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

and Lt. Monica Ayon, AA/PIO, California Men’s Colony

Historic photos compiled by Eric Owens, CDCR Staff Photographer

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.