Caring for pets is one way to teach people how to be responsible while also offering companionship, whether inside or out of prison. While pets help people show compassion, skills learned while caring for animals can even translate into jobs after incarceration.

Throughout California prison history, pets have helped normalize the environment for those who live and work inside the state’s prisons.

Befriending pets in prison

In his 1950 book, “The San Quentin Story,” Warden Clinton Duffy recounts some of the pets adopted by the incarcerated population.

“In San Quentin, any little thing that turns the mind from normal routine is a shaft of light in a shadowy world,” he wrote. “Only in prison would you find a man who befriended a two-legged mouse and built a tiny ramp on which it could reach a nest above his bed. The prisoners’ search for companionship has made pets of seagulls, turtles, (rodents, insects,) and a tame duck.”

Decades later, a turtle’s San Quentin escape was reported around the world. In 1974, a 14-inch-long turtle, one of many firehouse pets, got out of its enclosure and decided to explore the surroundings. The story was reported by United Press International, May 2, 1974. Their eagle-eyed reporters picked up the story from a small piece in the San Quentin News.

The cats of Folsom

According to a 1935 newspaper clipping, a cat roamed the halls inside Folsom State Prison. The friendly feline, adored by staff and the incarcerated population, had a habit of snitching on those who smuggled food into their cells.

“Rusty, the ‘stool pigeon cat,’ stills roams the old cell block with more freedom than anyone, even the guards,” reported the Stockman’s Journal, Dec. 21, 1935. “Rusty became famous 10 years ago (because the cat) would unfailingly discover prisoners when they broke rules by preparing food in their cells. (Prisoners) would smuggle food from the mess table with the idea of preparing a snack before turning in for the night.”

At the time, food was not allowed in the cells. They also were not allowed to possess ways to cook the food, but the rules didn’t stop some from trying. “Now and then a prisoner constructs a crude toaster or electric stove, (then sneaks) it into his cell,” the newspaper reported. “On such occasions, Rusty may be depended upon to head directly toward the cell from which the aroma of food emanates, sit outside and meow. Invariably, this attracts a guard.”

Blue and Chirps

Blue, a hungry kitten found in the prison yard and believed to be the offspring of Rusty, was adopted by a man serving a life sentence for murder. Another person serving life found an abandoned finch in a nest outside the window of the print shop. Both animals were nursed back to health and raised together by their two unlikely adopted caregivers.

Soon, Blue and the finch, named Chirps, became famous. Chirps was raised by the prison photographer, with the photos receiving widespread attention.

“More recently, stories and pictures of Blue and Chips received wide circulation,” according to the report.

Losing a legend

When Rusty passed away in 1938, the cat’s obituary was published around the country.

“For 16 years, Rusty rambled the cell block of Folsom Prison. He won distinction by his ability to detect food prisoners sought to hide in their cells,” reported the Associated Press, Jan. 29, 1938.

Joseph Doherty, clerk with the warden’s office, said the cat was very reliable. “He would go to a cell door and sit there until a guard came if he detected food,” Doherty said.

Wildlife and those serving time

Wildlife, and stray dogs, often find themselves in prisons or conservation camps. In the 1930s, a newspaper reported just such an occurrence.

“A California prison camp has a pet deer, which follows one prisoner all the time. The prisoner was sent up from Fresno for murder,” reported the Knoxville (Tennessee) Journal, Dec. 5, 1932.

When Inside CDCR visited Eel River Conservation Camp in 2021, we were introduced to two camp dogs: Wishbone and Belle.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Office of Public and Employee Communications

Sources:

- “The San Quentin Story,” by Warden Clinton Duffy as told to Dean Jennings, published by Double Day, July 1950, and Pocket Books, November 1951.

- Knoxville Journal, Tennessee, Dec. 5, 1932

- Stockman’s Journal, Omaha, Nebraska, Dec. 21, 1935

- United Press International, May 2, 1974

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.

Learn more about California prison history.

Explore CDCR history

SQ Captain Rivera Smith served nearly 4 decades

Rivera Smith was the longest serving staff member at San Quentin (SQ) when he passed away in 1950, serving nearly…

Echoes from the Past: Restoring history’s missing pages

While researching stories for the Unlocking History series, we often find damaged documents, missing photos, or incomplete information. One example…

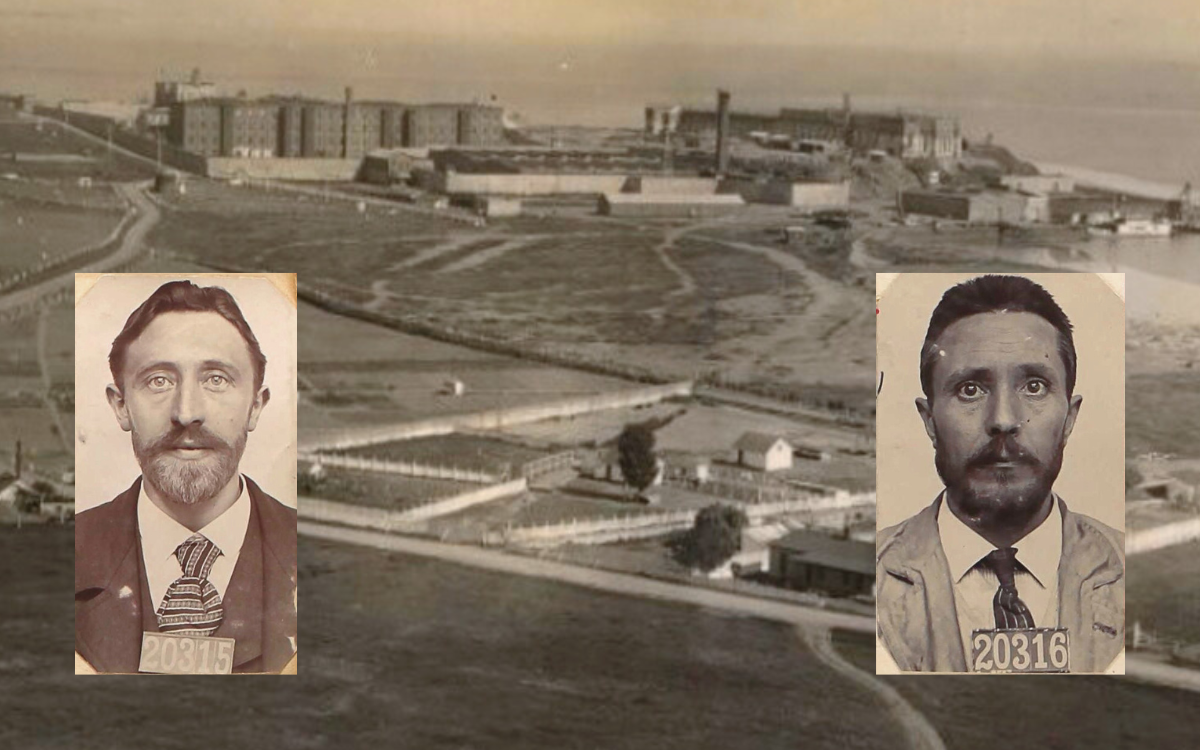

Family seeks information on 1903 counterfeiter

A recent question came across the Inside CDCR desk regarding a counterfeiter who was incarcerated at San Quentin in 1903.…

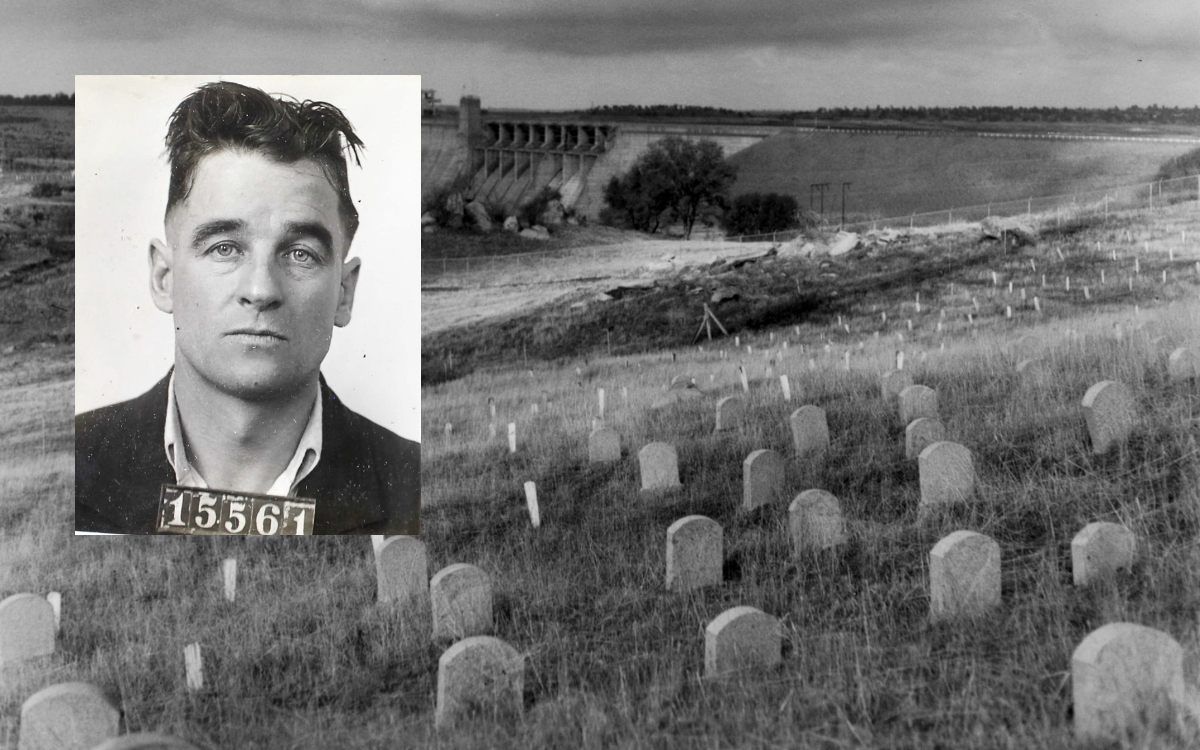

Cemetery Tales: Harry Stewart, Fresno embezzler

In our final Cemetery Tales of the season, we look more closely at Harry Stewart, early 1900s embezzler, thief, and…

Cemetery Tales: Meet JE McKim, thieving drifter

In our third installment of this month’s Cemetery Tales, we look at a drifter with a long criminal record dating…