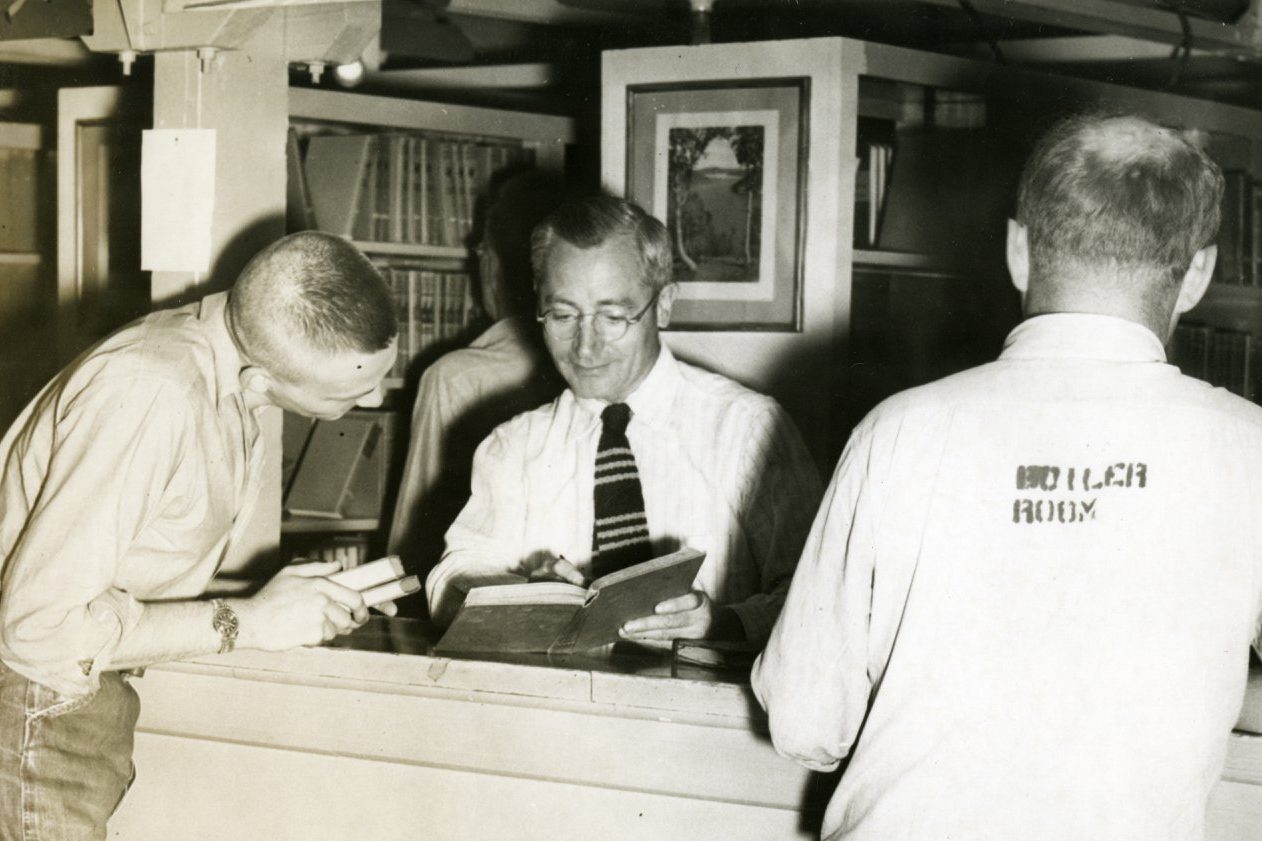

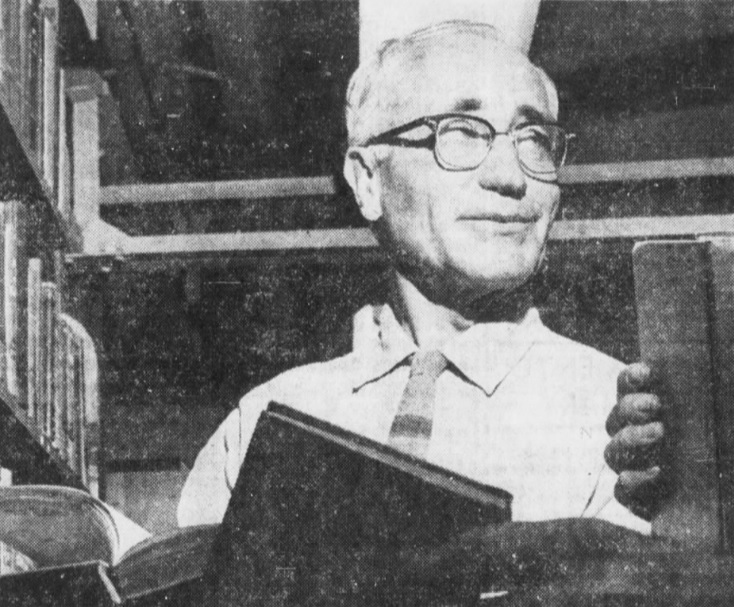

A 1956 report of the state prison library program emphasizes education, rehabilitation and personal growth. Herman K. Spector, the librarian at San Quentin and the supervising librarian for the department, penned the report. He’d been in charge of the San Quentin prison library since 1947.

He advocated for more educational and recreational books, as well as those focusing on self-improvement. His report lists achievements, emerging issues and the rehabilitative benefits of reading.

Prison library report outlines rehabilitation program

The 1956 report is simply titled “The Library Program of the California State Department of Corrections.”

Director of Corrections Richard A. McGee pushed the need for educational opportunities and professional standards across all positions in the department.

“Reading … good literature and the study of technical books … generally have a constructive influence. Consequently, a good library, operation on professional standards is an important segment of the rehabilitation program at each of the institutions of the Department,” he wrote. “The majority of persons committed to our institutions are lacking in both academic education and vocational training. The library provides the means whereby the willing and conscientious inmate can remove many of these deficiencies.

“Development of good habits to occupy leisure time is also important to all individuals, whether in confinement or not. Properly conducted libraries can be of assistance in providing materials for use in the self-advancement program.”

According to Spector’s report, the Prison Reorganization Act of 1944 instructed prison staff to regard each inmate “as an individual in need of treatment. Our ultimate objectives would be attained only if we studied each inmate as an individual and treat him (according to) his specific needs. Eventually he would assume his own responsibilities of citizenship.”

Rehabilitation objectives of the prison library

“The primary purpose of the library is to assist in the general training and welfare of the prison population leading toward education, vocational and personal adjustments and advancement,” Spector wrote.

He suggested offering “courses for personality development or self-improvement; helping inmates to enjoy reading as a leisure time activity; compiling reading lists for staff members in connection with their work in prison and their own professional advancement; assisting inmates in their literary and artistic endeavors; reviewing manuscripts of the inmates whenever the institutional polices assign this work to the librarian.”

He based his recommendations on the rehabilitative goals listed in the department’s 1949 prison library manual.

Librarian’s training and duties

“In 1947, a trained senior librarian was assigned to San Quentin,” he wrote. “We now have full time librarians (grade III) at Chino, Folsom, San Quentin and Vacaville.”

The Correctional Training Facility’s librarian was a grade I position. In Tracy a correctional officer acted as librarian.

The California Institution for Women had “a qualified teacher (for) an hour a day to supervise the library services. At San Luis Obispo, the Supervisor of Recreation devotes a portion of his time to the work of the library. At our newest facility at Tehachapi, a branch of Chino, the Supervisor of Prison Education is responsible to carry out the library program. Our librarians are responsible for all the activities of the library.”

The librarian reported to the care-and-treatment Associate Warden.

“The care-and-treatment program, under which the libraries function, is supervised on the staff level, in Sacramento, by the Classification Bureau,” he wrote. “This agency provides professional advice to all the librarians in the Department.”

Professional librarians hired

The department’s Supervising Librarian, grade IV, worked through the Central Office while also serving as the San Quentin librarian.

Librarians took on other roles as well, including giving “guidance to inmates in their reading, or through instruction, make them more familiar with the uses of the library.” They also handled “clubs, debating teams and discussion groups.”

“When men … are transferred from one institution to another, it is important that the librarian in the receiving institution make an effort to sustain … reading habits,” he wrote.

“(A log of inmate library activities) becomes an official Departmental record of the man’s participation in the rehabilitation program,” he wrote.

The reported also focused on Conservation Camp libraries, their services and ways to improve.

“The correctional library can contribute directly to the meaningfulness of the overall therapeutic program (and) does help men in their preparation for parole and their ultimate adjustment in the free world,” he wrote, making the case the each correctional library “meet established standards.”

“Funds allocated (for the libraries) admittedly reveal the recognition of reading materials as aids in correctional rehabilitation,” he concluded.

Who was Herman Spector?

He was hired after a nationwide search, having cut his literary teeth in the penal institutions of New York in the 1940s.

Back then, he was part of the effort to prepare for life after World War II.

“We propose to go ahead and be ready for the great changes that are coming. That is why we are planning now,” wrote New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia in the brochure “New York City’s Post War Program.”

To help with this effort, Spector compiled and published a 140-page book of resource material.

“Thanks to the vision and determination of our own Commissioner of Correction, Peter Amoroso, M.D., we were privileged to prepare this bibliography for post-war distribution,” Spector wrote in May 1944.

He promoted writing as a form of rehabilitation, advocating for newspapers created by the incarcerated population.

“Prison publications reflect the moods, minds and attitudes of the prison wherein they are published. They promote self-expression, a realization of one’s obligation to communal life, and an interest in local and world affairs. They serve as an outlet or ‘safety-valve’ for dynamic outbursts which, if suppressed, might develop introverted, anti-social tendencies where none had previously existed,” Spector wrote, going on to estimate there were 75 prison publications in the U.S.

“By and large these publications are devoted to the cause of progressive penology, which might well be expressed by the following declaration of principles:

- An understanding of (the prison system’s need) to contribute toward the solution of the crime problem.

- The admission, after proof, that men can be permanently rehabilitated to useful community life and the adoption of socializing and rehabilitative measures behind prison walls, followed by equally progressive after-care.

- The realization that such rehabilitative or re-socializing influences are completely neutralized, unless and until, the desire for improvement stems from within the prisoner himself.

- Creating and maintaining this desire.

“Toward this set of aims, ideals and obligations, the prison press is … solemnly dedicated.”

Prison library focused rehabilitation was not a cookie-cutter approach

In his book, he republished a 1937 section of the address given by American Prison Association President William Ellis.

“We know that each offender must be treated as an individual. … He must be helped to want to reach a goal that is essentially his own. In fulfilling our duty so as to administer prisons that they may help to prevent crime, it is obvious that our major interest must be in society itself,” Ellis said.

Did you know?

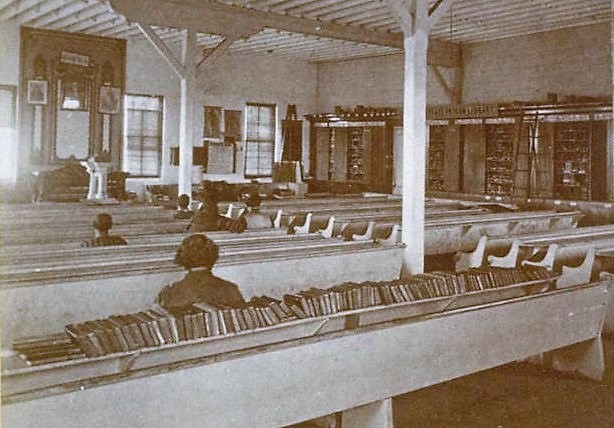

Libraries go back to the early days of the state prison system. On March 23, 1859, the California State Legislature passed an act “to provide for the establishment of a State Prison Library. (The) person (in) charge of the State Prison (is) required to purchase (books) for a State Prison Library and to make rules (allowing for) the moral and intellectual well-being of the convicts.” The Legislature authorized $500 to purchase books.

Read other Unlocking History and Time Capsule stories or explore the inmate-produced San Quentin News.