From 1851-1982, victims fought for their voice

Victims and survivors have long fought to have a voice in investigations, trials, sentencing and parole hearings.

(Editor’s note: This story originally published in 2018.)

Since the first incarcerated people boarded the Waban prison ship in 1851, crime victims and their families have fought for their rights. Despite their efforts, it took more than 130 years before victims found their voices.

In 1982, California voters passed Proposition 8, officially recognizing victims’ rights. Then, in 1988, the state corrections department established a special victims office, today known as the Office of Victim and Survivor Rights and Services (OVSRS).

(Learn more at the OVSRS website.)

Inside CDCR delves into some of the stories of those early victims and survivors, finally giving them a voice.

In the early days of the state prison system, victim resources were virtually nonexistent. What few services were available were offered by charitable organizations.

Family shattered by murder

While officially recognizing victims didn’t happen until the 1980s, many fought to tell their stories long before they had a platform.

Such was the case with a grieving father who begged for justice.

“Dramatically pleading with the jury that justice be done, W.C. Dillingham, father of Stella Luitweiler, who was murdered by her husband, George C. Luitweiler, took the witness stand at the inquest held over her body in Bresee Brothers’ morgue yesterday afternoon. (He) graphically told of the strife and differences between the young married couple,” reported the Los Angeles Herald, July 20, 1910. “He (testified) the husband had abused her (many) times (despite Stella) always ready to do anything for him.”

According to reports, the husband approached Stella and her sister May while they ate breakfast. Passing them by, he mentioned something about the property, then went out to the porch. The house had been a source of friction because he wanted to sell while she didn’t.

Only a few days prior, Stella petitioned the court for an injunction, preventing her estranged husband from selling the home out from under her and their 4-year-old child.

When he returned to the dining area, he drew his pistol, firing a shot at Dillingham, knocking her to the ground. Then he fired a second round, this one striking Stella in the head. Dillingham tried to run for the door, but Luitweiler shot her a second time.

Eyewitness account of murder

“May Agnes Dillingham, sister of the dead woman and the only witness to the tragedy, was shot twice by the infuriated husband in an attempt to kill her,” the paper reported.

After shooting the sisters, the husband went upstairs and swallowed cyanide. Unfortunately for him, the poison didn’t have enough time to act before help arrived. Authorities found George Luitweiler in time to save his life and put him on trial.

“It was cold-blooded murder,” Dillingham said from her hospital bed. “He was not angry, not a bit. (When) he came back after a little while (from the porch), without saying a word, he shot me in the shoulder. The bullet knocked me down and he shot my sister. Then, he took another shot at me.”

Buster Luitweiler, their 4-year-old son, had been playing at a neighbor’s house, but discovered his mother’s body after running home when he heard the gunfire.

Ripple effect on families

The case deeply affected the families of all involved.

“Brooding over the troubles of his brother, Jesse Luitweiler, 35, a machinist, was taken to the receiving hospital yesterday (after a mental break),” reported the Los Angeles Herald, Dec. 12, 1910.

“Worn out with the strain of seeing her son tried for murder, Sophia Luitweiler, mother of (the accused murderer), yesterday collapsed in Judge Willis’ department of the superior court,” reported the Herald, April 5, 1911.

Meanwhile, the murdered woman’s parents divorced in 1916. Her father died three years later.

What happened to George Luitweiler?

While Luitweiler was first charged with murder, he was later declared insane and committed to the Patton asylum. In May 1912, he escaped the hospital but didn’t make it very far. Two months later, they found his body in a nearby desert.

Family of belfry murder victims cope with loss

In 1895, the murders of two young women set San Francisco on edge. Their bodies were found in a church and the finger of blame was pointed at Theodore Durrant, a medical student who also served as an educator at the church.

Murder victim Blanche Lamont’s 16-year-old sister, Maud, spoke about the pending murder trial. Blanche had gone missing for 10 days when her body, as well as that of Minnie Williams, were discovered at the church. Blanche’s nude body was found in the belfry of the church while Williams’ body was found mangled and shoved in a small room. The press dubbed it the “belfry murders.”

“Her young face was shadowed by a seriousness beyond her years while she talked of the crime,” reported the San Francisco Call, July 18, 1895. “She returned on Tuesday from Dillon, Mont., where she spent her vacation with her mother and older sister. ‘Mamma is bearing her trial well,’ she said, ‘although she was completely crushed at first.'”

The paper said the young lady would continue living with her aunt, Mrs. Noble, and attend school in the city.

Difficulty speaking about murders

“Noble cannot yet talk of the tragedy without emotion. ‘Oh, we know, that is we feel certain, Theodore Durrant is guilty,’ Noble said, ‘and to think that I urged her to accept his attentions. How we suffered in the 10 days when we did not know where she was, and afterward.’ Her eyes overflowed at the thought,” the paper reported.

When Maud Lamont was called to testify at trial, it caused a stir. A newspaper reporter vividly described the scene.

“When District Attorney Barnes (called) Maud Lamont, every head in the courtroom was turned to the door. Presently there entered a slight, girlish figure, dressed all in black, with a wealth of auburn hair that hung in a braid nearly to her waist,” reported the San Francisco Call, Sept. 12, 1895. “Every eye watched her progress through the crowded courtroom to the witness stand.”

Durrant receives death penalty

When Durrant was convicted of murder, Blanche’s sister and aunt were in the courtroom.

“When the verdict was announced, Maud Lamont sprang from her seat, clapped her hands and then cried,” reported the Los Angeles Herald, Nov. 2, 1895. “Noble mixed smiles with tears.”

Durrant was executed in 1898.

Meanwhile, Williams’ murder didn’t receive the same level of attention since Durrant was never tried for her death. The Williams family, though, suffered the same loss.

“Possibly the last scene in the drama which (Durrant) was the villain was enacted yesterday when A.E. Williams, father of Minnie Williams, (asked) Captain Seymour for (her possessions) which were taken from the house in Alameda where she was employed,” reported the San Francisco Call, May 17, 1900. “Williams said he was going to Cape Nome. (Since) the girl’s mother in Toronto, Canada, asked for her effects, he wanted to send them to her before he left the city. An order was obtained from Judge Cabaniss on the property clerk for the (items).”

Did you know? California’s laws regarding filming inside prisons dates back to Durrant.

Gas Pipe Gang leaves path of devastation

Today, the families of victims can be reimbursed through restitution paid by those sentenced for the crime. This wasn’t the case a century ago.

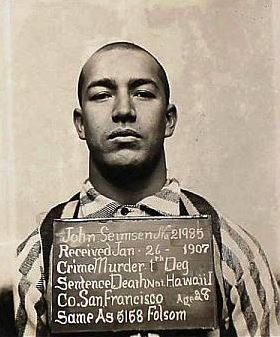

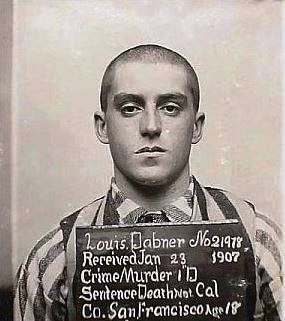

In 1906, a small gang of men wielding gas pipes terrorized San Francisco in the wake of the great earthquake. In a series of escalating robberies, they admitted to killing several men but were only tried for the murder of M. Murakata, manager of Kimmon Ginko bank. They also beat bank clerk A. Sasaki, nearly killing him.

Due to his injuries, Sasaki could not recall the events on the day of the assault. Luckily for prosecutors, he did remember one of the men coming into the bank the day prior. According to authorities, the men were casing the bank.

Sasaki, recovering in a hospital bed, and Dockweiler positively identified John Siemsen.

“Siemsen had a rare chance to show the bravado in which he delights when he was confronted by J.H. Dockweiler, the engineer who was held up by (the duo), and Sasaki, cashier of the Japanese Bank, who was all but murdered by the (culprits). The meetings between the murderer and those who he had slugged where technically ‘identifications,’ but the criminal was as willing to identify the men he had robbed as they were to attest to his guilt,” reported the San Francisco Call, Nov. 9, 1906.

“Judge Coffey yesterday allowed the claims against the estate of Murakata, the Japanese banker who was killed by Siemsen and Dabner, for $220 actual burial expenses and $360 additional (for cultural customs),” reported the San Francisco Call, April 10, 1907. “It appeared that of the bank’s $25,000 capital, Murakata owned only $1,500, so there was little left for the widow.”

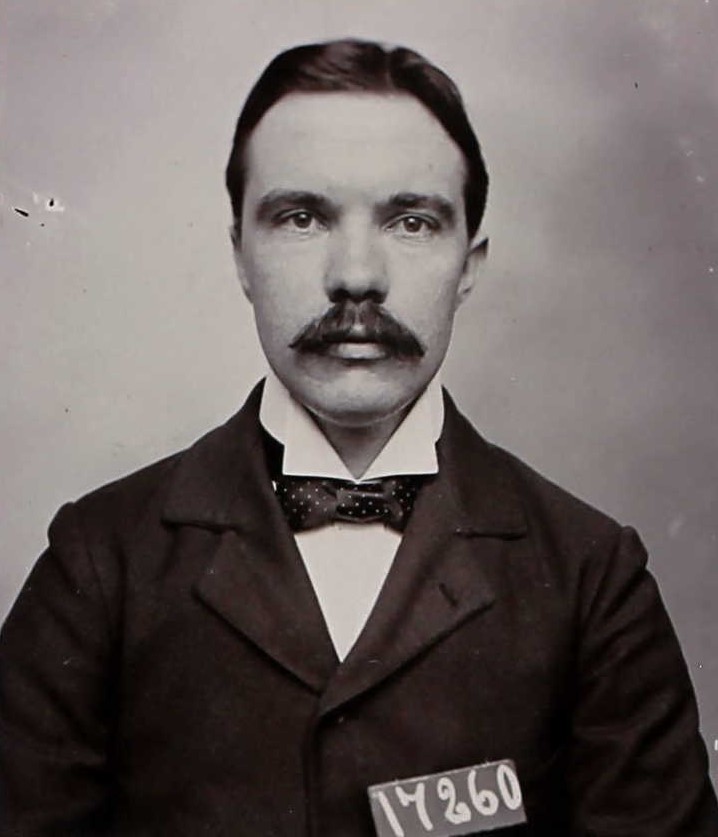

Siemsen, Dabner get death penalty

Siemsen and Dabner were executed by simultaneous hanging at San Quentin. One of those witnessing the execution was Henry Behrend, a jeweler who was robbed and beaten by the convicted criminals. He was their final victim, suffering severe injuries from the beating. Behrend’s struggle is credited with leading to their capture.

“I’m glad they’re there (on the gallows). It’s better their lives than mine, and God knows I fought with them once to see which it should be,” he told the San Francisco Call, Aug. 1, 1908.”Yes, I’m satisfied now. I wanted to see them hanged. I’m deaf. That’s what Dabner did to me. He beat me over the head with an iron bar until I lost my hearing forever and nearly lost my life.”

The victim’s doctor was nearby just in case. Since the attack, Behrand’s health began to fail but he insisted on seeing the two pay for their crimes.

“Dabner and Siemsen were guilty of and confessed to three murders. They first killed Johannes Pfitzner, a shoe dealer, on Aug. 19, 1906, by beating him to death with a gas pipe. Sept. 14 of the same year they assassinated William Friede, a clothing merchant, in a similar manner, and on Oct. 3, they murdered M. Murakata, president of the Kimmon Ginko Japanese bank and nearly killed his cashier, A. Sasaki. All the murders were committed in the daytime and were as bold as they were horrible in their details,” the newspaper reported. “It was while attempting to rob the jewelry store of Henry Behrend on Nov. 3, 1906, that the plucky jeweler made a fight which led to their capture.”

Sasaki, too feeble to witness the hanging, sent his brother in his place.

Widow fights killer’s release

In 1903, Patrick Herron took his attraction to Katie Williamson too far.

When the Williamson family made their way through the Sierra Nevada mountains headed for Nevada, Herron discreetly followed. While camped outside Reno, Herron approached the family and “demanded they allow their daughter to marry him,” reported the San Francisco Call, July 9, 1905.

Her father, William Williamson, refused. Herron drew “a gun and shot the father in the back,” the paper reported. Williamson was slain one month shy of his 40th birthday.

Two years later, Herron was serving a 20-year sentence in the Nevada penitentiary when he applied for a pardon.

Hearing of this, the Williamson widow traveled to Reno “from California to protest against granting his request,” the paper reported. “She has employed counsel and will make a great effort to make the murderer serve the full penalty of his brutal crime.”

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Learn more about National Crime Victims’ Right Week 2023.

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.