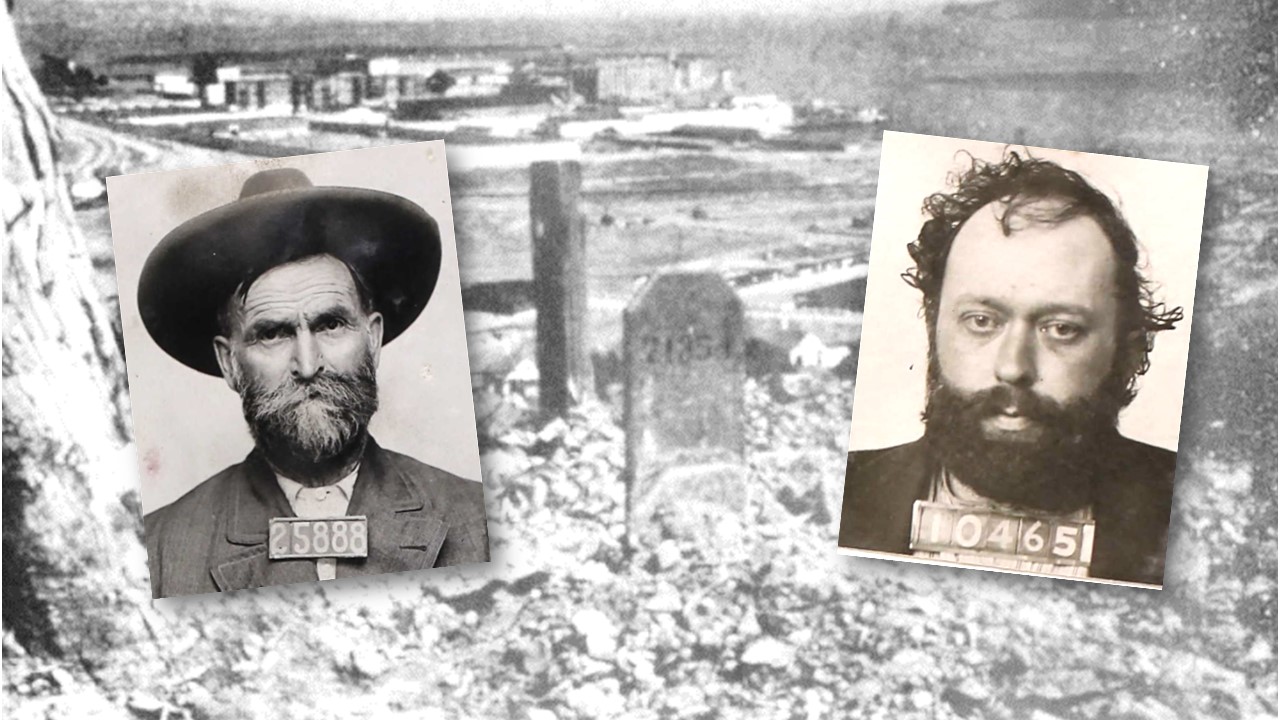

The second installment of this month’s Cemetery Tales looks at two incarcerated people at different stages in their lives when they passed away: Raymond Blade and Henry Hunt.

Blade, 19, found himself in Folsom State Prison serving two years for burglary when he was killed during an escape attempt. At the other end of the age spectrum, 81-year-old Hunt, serving a 40-year sentence at San Quentin, died in prison.

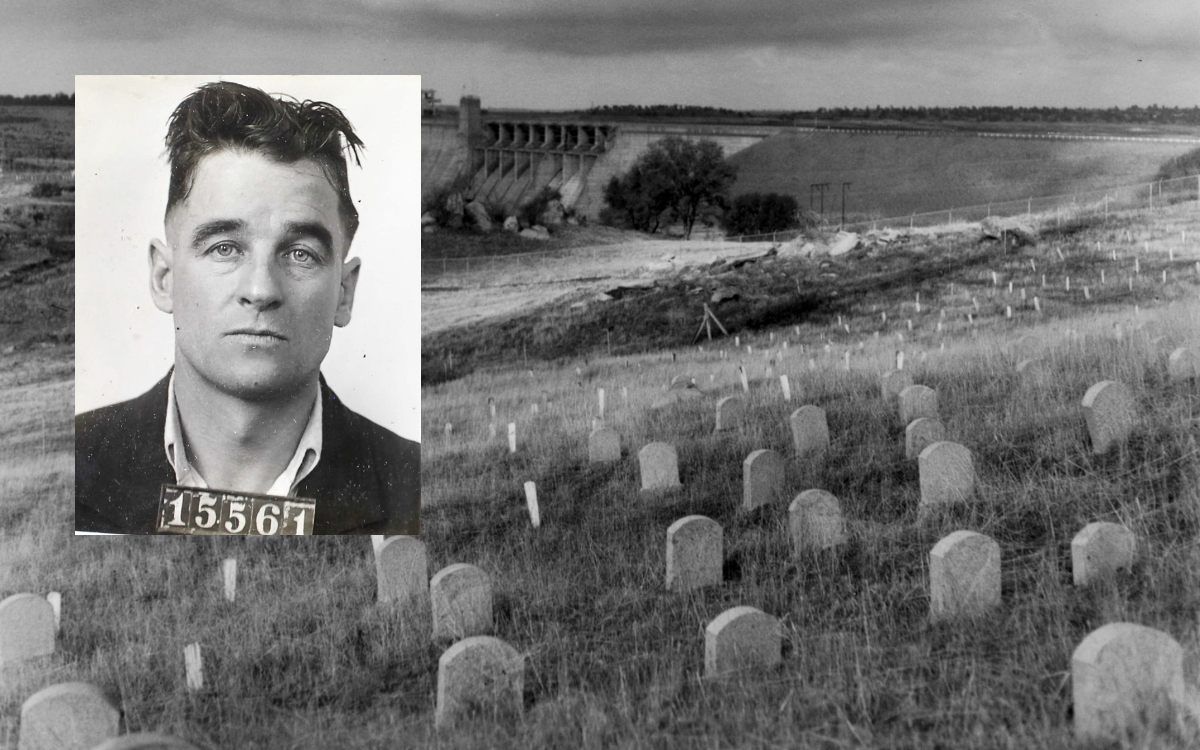

Raymond Blade: Youth’s journey ends at Folsom Prison

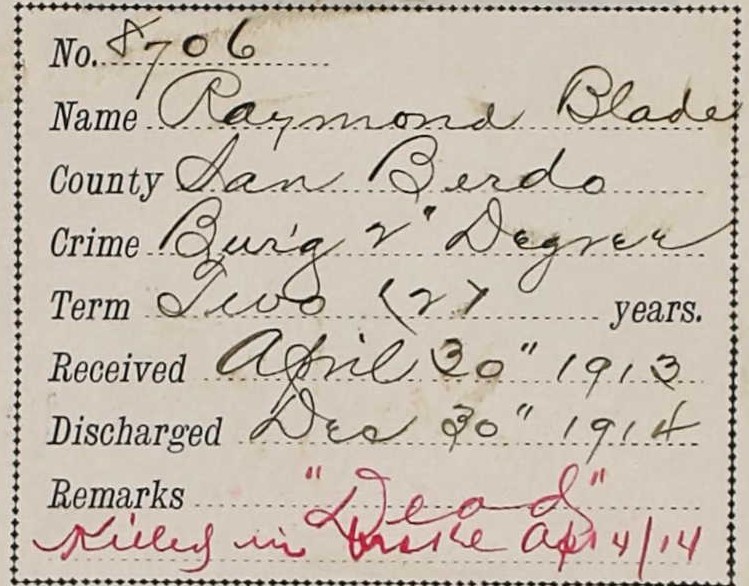

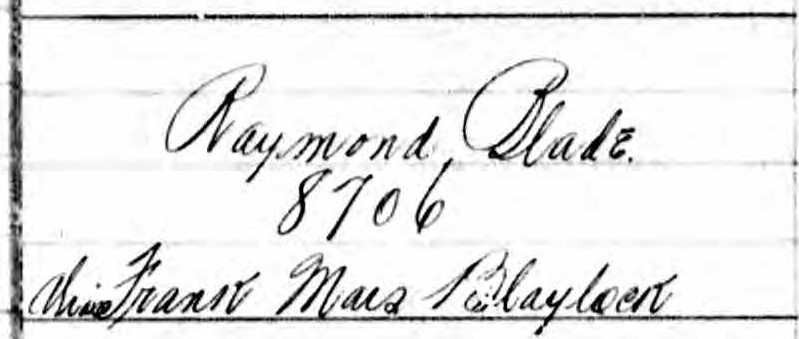

Details are sparse when it comes to 19-year-old Raymond Blade, aka Frank Mars Blaylock.

According to 1913 news accounts, Blade had befriended William Frake, known as the “goat man” of Daggett. At some point, Blade swiped clothing and a six-shooter from Frake’s tent and fled.

Frake alerted authorities and a sheriff’s deputy quickly apprehended Blade at Newberry.

When he went before the judge, Blade said the officers were lucky to be alive.

“It’s a good thing the officers got the drop on me first,” he told the judge, “(Otherwise,) I certainly would have let them have all I had.”

His bravado and threats of violence led the judge to sentence him to a two-year term at Folsom State Prison.

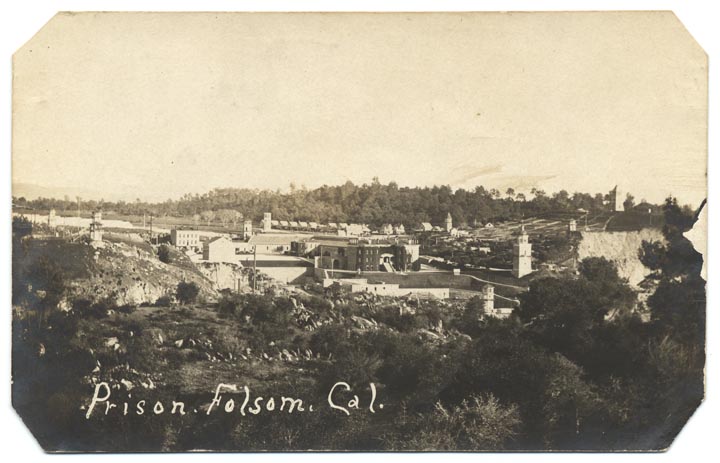

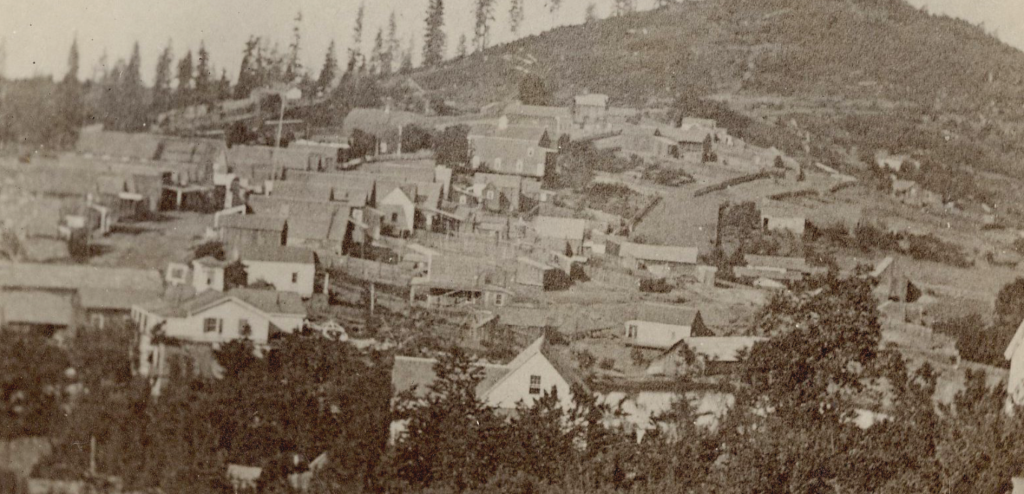

While in prison, Folsom was in the process of building a mental health facility on a nearby hill, commonly known as the “bug house.” While not yet complete, some incarcerated people were serving time in the new cells, helping prepare the building for activation. Alert custody staff then overheard a few planning an escape attempt.

Staff also warned them not to try anything.

Since the building was incomplete, some security features were not yet in place, including the steel doors. “Heavy wooden doors served instead,” according to news accounts.

Warnings not heeded

Guards E.S. Westbach and Frank Fillett suspected there would be trouble and were ready, armed with rifles.

At about 4 p.m., Saturday, April 14, the incarcerated men made their move.

“With a rush, the 13 incorrigibles confined temporarily in the cell house built for the detention of the criminally insane battered down the wooden doors and rushed into the main corridor on the second tier,” reported the Daily News of Dayton, Ohio, Daily News.

Blade held part of a window sash, swinging it around while threatening to kill anyone who got in their way. The guards ordered the men to halt and return to their cell, but the prisoners pushed forward. Then, the guards opened fire.

“Then both Fillett and (I) fired simultaneously. Blade and Rivera, the leaders, fell with the first two shots. Barron snatched up the sash dropped by Blade and headed directly for me. I let go with another shot and so did Fillett. Barron dropped in his tracks, but the others kept coming. We both fired again and then Brady and Ellsmore dropped. This seemed to frighten the others for they halted, turned and ran back to their cells,” Westbach recounted.

“Five men fell, one after another. Seeing the fate that had befallen their leaders, the remaining eight ran back into their cells and begged the guards to quit shooting,” the newspaper reported.

The warden commended his staff for holding the line.

Warden: Staff ‘did what they were expected to do’

“Fillett and Westbach did just what they were expected to do,” Warden J.J. Smith said. “The men were bent on freedom and if they had not fired when they did, it is almost a certainty that one or perhaps both of them would have been brained by the sash carried by Blade.”

Westbach told investigators, “There was nothing for us to do but fire when the men refused to halt. We were sorry we had to kill but it was our lives or theirs.”

Two days later, Blade and his deceased co-conspirators were buried at the Folsom State Prison cemetery.

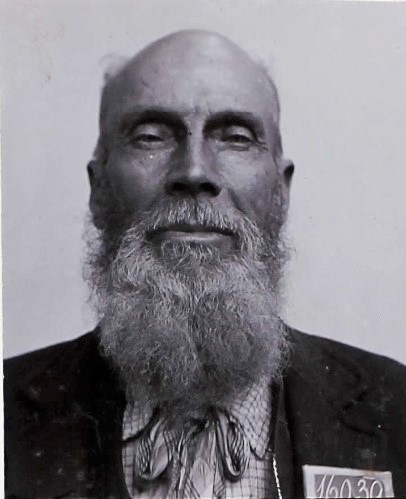

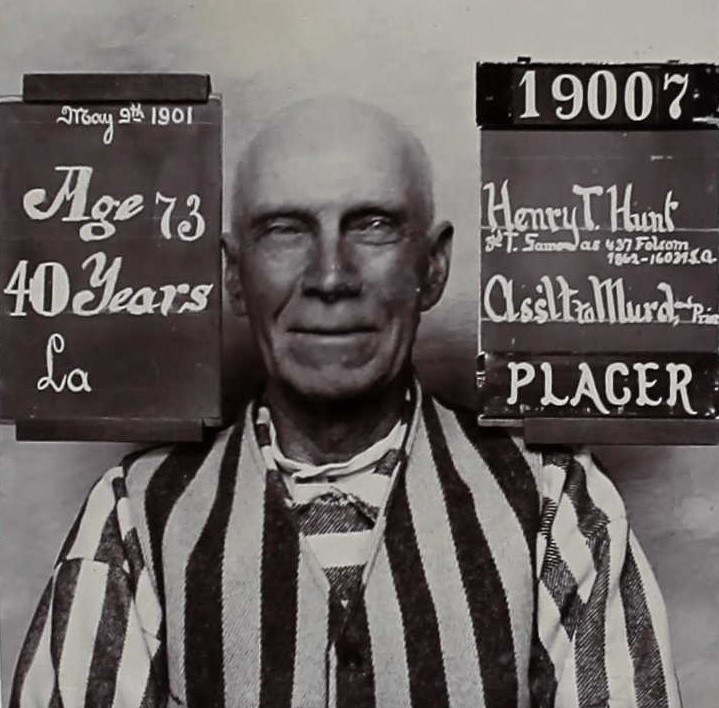

Henry Hunt: Decades of criminal behavior

A news article in the Los Angeles Herald, Aug. 5, 1894, describes Henry Hunt as “a well-known criminal character in this (area)” and “an awful old man.”

“The old-timers know him and how he killed Officer George Gillis. He received a life sentence, but was afterwards commuted to 20 years,” reported the newspaper. “In some mysterious manner, a pardon was secured and after 11 years’ imprisonment, Hunt (was released) in February.”

Just four months after being released, Hunt once again found himself in legal trouble. “It is alleged he (lured) a miner named Samuel Holroyd up the Arroyo Seco and attempted to rob him June 22,” reported the newspaper.

Setting the trap

Hunt said he had a decent coal claim in the Arroyo Seco and asked Holroyd to accompany him on a brief prospecting excursion. Knowing Holroyd was headed back to Colorado that afternoon, Hunt promised they could “easily get back in time for the 2 o’clock train.”

Holroyd knew Hunt as Frank Day. Afterall, Hunt had a criminal record and had been convicted of murdering Officer Gillis.

Once in the hills, Hunt told Holroyd he couldn’t find the claim. The victim then turned and started back toward town when he was struck over the right ear with a pipe.

“It staggered him but did not knock him down. He turned and found Hunt aiming another blow at him,” the newspaper reported.

Dodging the second swing, Holroyd drew his pistol and shot Hunt through the hand. Holroyd then returned to town and went directly to the police. Meanwhile, Hunt managed to get to the road where he flagged down help. He too then went to a nearby police station, claiming Holroyd shot and robbed him.

Can’t outrun his past

A few of the veteran police officers recognized Hunt as the man they sent to prison for killing Officer Gillis.

“Hunt’s hopes (of not being recognized) were crushed when Officer Steele walked up to his bed in the receiving hospital and said, ‘Well, Hunt, how are you? I thought you were in Folsom for life.'”

He was sentenced to 10 years at San Quentin for assault to rob. He served until February 1901, when he was released.

Hunting for the next victim

Hunt, now going by the name Henry Jackson, made his way to Placer County and the Stevens ranch near Iowa Hill. It was there he met Charles Warner, a bachelor with a modest ranch.

“Jackson (Hunt) hung around Warner’s place several days, representing himself as the owner of a good fruit ranch in Los Angeles County, and talked of buying Warner’s place,” according to the Los Angeles Times, Aug. 29, 1901. “On the evening of April 6, 1901, while Warner was feeding his horses at the barn, Hunt came in with a borrowed gun. (He) shot Warner twice without provocation or warning and robbed him of $30 and a breechloading shotgun. Hunt left Warner for dead, but he recovered sufficiently to be able to testify against Hunt.”

Hunt fled to Tehama County where he was arrested and returned to Placer County. At his trial in Auburn, the judge sentenced him to 40 years at San Quentin.

Hunt’s final words

“Now the state is boarding Henry Hunt, alias Samuel Hunt, alias Frank Day, alias Henry Jackson, for his third term,” the newspaper reported.

For eight years, Hunt tried legal avenues to secure a release, to no avail.

“Hunt, the oldest prisoner in San Quentin whose crimes date back to 1881, escaped 32 years of his third sentence by death,” reported the San Francisco Call, Oct. 18, 1909. “Having no friends or relatives, (he) was buried in the prison graveyard with a headboard bearing the number 19007 to mark his resting place.”

According to the news account, on his deathbed with prison Dr. Wade Stone at his side, he feebly muttered, “Well, Doc, I expected a pardon, but this is better.”

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Office of Public and Employee Communications

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.

Cemetery Tales

Cemetery Tales: Harry Stewart, Fresno embezzler

In our final Cemetery Tales of the season, we look more closely at Harry Stewart, early 1900s embezzler, thief, and…

Cemetery Tales: Meet JE McKim, thieving drifter

In our third installment of this month’s Cemetery Tales, we look at a drifter with a long criminal record dating…

Cemetery Tales: Raymond Blade and Henry Hunt

The second installment of this month’s Cemetery Tales looks at two incarcerated people at different stages in their lives when…

Cemetery Tales: John Beebe and Joseph Balado

The first Cemetery Tales story for 2025 looks at the lives of career criminal John Beebe and Joseph “Jose” Balado,…

Cemetery Tales: Estranged husband and a robber

In this month’s fifth installment of Cemetery Tales, we examine the stories of an estranged husband and a robber who…

Cemetery Tales: The farmer and a self‑appointed king

Our fourth Cemetery Tales looks at farmer-turned-double-murderer George Biggs and Judah Benjamin, a self-proclaimed king. Both men ended up in…