Joseph Wess Moore was a 15-year-old farm boy who joined the Union Army to fight in the Civil War. Decades later, the Civil War veteran found himself sitting in San Quentin serving a life sentence for murder.

While incarcerated, he found a passion for literature as stories transported him beyond the walls of the prison. Soon he put pen to paper to craft his own tales, publishing some of his writings in a small book used to promote prison reform.

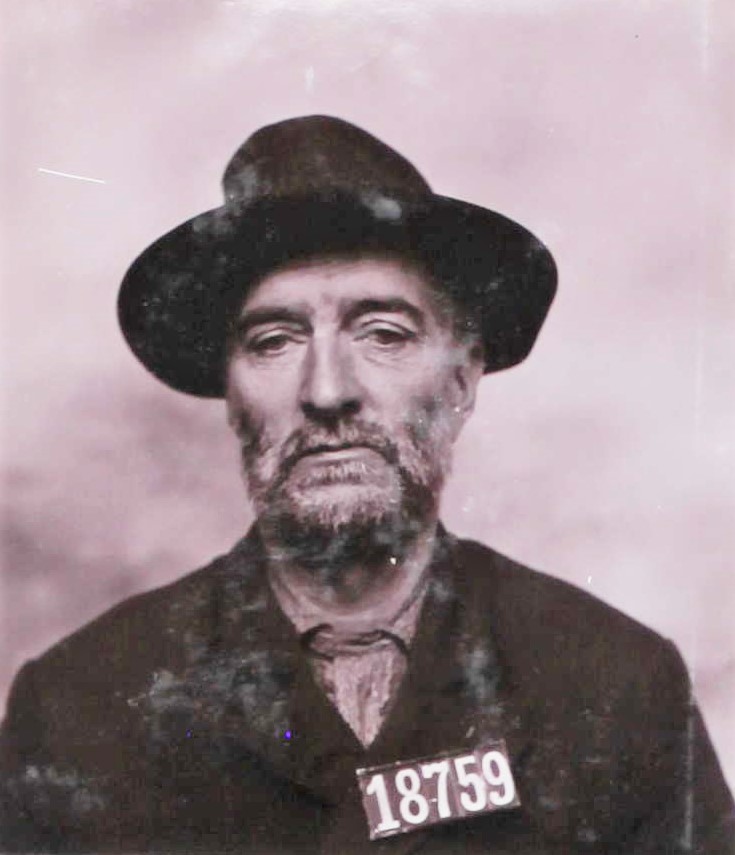

Veteran Joseph Wess Moore advocated prison reform

In 1908, Moore’s fate turned around. He tasted freedom thanks to efforts of a military veterans’ group and the parole law. By 1909, his prison writings were compiled to create “Glimpse of Prison Life,” a booklet published by the newly created parolee-reintegration group, Society for the Friendless. He became an advocate for prison reform, providing assistance to paroled people. Unfortunately, his life as a free man didn’t last long. The 62-year-old Civil War veteran died of an apparent heart attack in 1910.

Part poetry, part essays, the 78-page booklet sheds light on life at San Quentin shortly after the dawn of the 20th century. The booklet also offers glimpses into the life of the Civil War veteran. Moore made no effort to hide his incarceration, putting his inmate number on the cover of the book, 18759.

This is the story of a combat veteran who didn’t adjust well to civilian life but found redemption in literature and helping others while incarcerated.

Farm boy becomes Civil War veteran

Moore was born to a much simpler life than the one he was destined to lead. He came into the world in 1848, part of an agricultural-based Quaker community. When the Civil War broke out in 1863, he enlisted as a private in Company B, Fifth Indiana Cavalry. He later transferred to Company H, Sixth Indiana Cavalry.

“When I was a fatherless, beardless lad of 15 summers, I wanted to go to war,” Moore wrote. “I saw my boy chums enlist (and) some of whom were but a little older than myself, so I determined to go also. But owing to my youth, it first became necessary for me to have my mother’s written consent. … I then walked away to join my comrades and to follow the fortunes of active service in times of war.”

He fought in the 1864 battle of Turner’s Ferry in Georgia and pushed on to the bloody battle of Atlanta. In 1865, at 17 years old, he was discharged.

He was 21 when Nancy Haines became his wife in 1869. They started a small family with two daughters but tragedy struck the military veteran. His wife passed away in 1876. He soon became the common law husband of Priscilla Horrocks Cade in 1877 in Nebraska.

Seeking to better their lot in life, the family headed west to the Golden State in 1900.

After just four months, Moore shot and killed 37-year-old Chastain Alverson in a dispute over a mining claim. After receiving death threats from Alverson, Moore said he tried to get an arrest warrant against the man but was unsuccessful.

While Moore claimed the shooting was self-defense, the court didn’t buy his story. He was given a life sentence.

Learning to live inside prison walls

Moore wasn’t like the others serving prison sentences. For starters, he was much older than most. Moore was 55 when he entered the gates of San Quentin. For the first 14 months, he worked in the jute mill, but declining health and injuries suffered during the war began to take a toll.

He was reassigned by Warden Aguirre as the prison librarian and so began his love of literature. When Warden John Tompkins replaced Aguirre, things rapidly changed. The new warden summoned Moore to his office.

“He came in hobbling on two canes. Tompkins accused him of having received smuggled tobacco from a guard,” according to an account reflecting on Moore’s time in prison. The story was published in the San Francisco Daily News, June 5, 1909. Moore denied the allegations. “Clad in dungeon clothes, he spent three days in the incorrigible cell.”

One of the prison directors, James Wilkins, overruled the warden once he caught wind of the incident. He ordered Moore released. According to Wilkins, the real issue wasn’t over tobacco. Rumors were flying of Moore trying to smuggle an article to a newspaper. Having earned the displeasure of the warden, Moore was back at the jute mill for almost two more years.

Moore looked forward to the visitor he received two or three times each week. His wife, Priscilla, had relocated to San Quentin to be near her husband. To help earn a living she worked in guard White’s home. She often brought Moore homemade treats. Unfortunately, Priscilla fell ill and passed away in 1903. Moore was not allowed to attend the funeral.

New warden gives Civil War veteran a second chance

Warden Edgar replaced Warden Tompkins. The new warden recognized Moore’s declining health so gave him a chance to recuperate.

“The sick prisoner was allowed to loaf about in the prison yard, to bask in God’s sunshine and look up into the blue vault of heaven,” the newspaper reported. “And when he had become well enough, he was put in charge of the condemned cells. This is an envied post, says Moore, for the work is light and the food the finest in the market. … Moore made many friends among the condemned men. He knew Siemsen and Dabner, the gas pipe thugs, well. As Siemsen passed to the death watch, he held out a shackled hand (to Moore) with a cheery, ‘Goodbye, dad.'”

A look at the brighter side

The newspaper also described some of the more positive aspects for those incarcerated at San Quentin.

“But there is a brighter side to San Quentin life,” the newspaper reported. “The men turn out at 6 o’clock in summer and 7 in winter. In the afternoon they are in their quarters at 10 minutes to 5, or on Sundays and holidays, at a quarter to 3. On the 4th of July and Christmas Day, there is a minstrel show. On Sundays, Moore taught Sunday school in the morning among the younger prisoners and preached when the chaplain had finished. (He) picked up his fiddle at 4 o’clock and played tunes for the boys to dance by, playing until they were tired. He learned to fiddle in the army.”

Moore’s favorite warden was John Hoyle, also known as the reform warden.

>> Learn more about Warden Hoyle.

“It was not that Hoyle let him loaf about the yard because his legs were half paralyzed, to write letters for illiterate prisoners. It was that Hoyle would go out of his way to hear a prisoner’s tale. There had been wardens who regarded the prisoners as beasts, to be thrown into dungeons on the words of stool pigeons. But big-hearted John Hoyle is not of these,” the newspaper reported.

“The sweetest acts of devotion I have ever seen in my life have been in prison,” Moore told the newspaper.

Brief taste of freedom

When he was paroled, he was outspoken in his efforts to give prisoners and parolees a chance to rehabilitate.

“The Society for the Friendless will (help) worthy prisoners now confined in San Quentin and Folsom, who have neither money or friends to assist them to secure parole. (They) will aid the needy and dependent mothers, wives and little ones of paroled and other prisoners, will look after the sick and distressed in all cases coming to our notice, no matter by whom so reported. There are, scattered throughout our state, many who suffer more than do those incarcerated, and upon whom the hand of scorn rests heavily,” according to Moore’s book, which had a few pages written by the Society.

His reform efforts raised eyebrows with the prison staff and local law enforcement. He was re-incarcerated but was paroled a second time on the promise he would leave the state and never return.

Moore, who had no family in the west, agreed to live with his brother in Indiana. With that, he bid farewell to California and boarded a train heading east. At the train station near his destination, the 62-year-old Moore collapsed and died of an apparent heart attack.

Moore also served time with Griffith J. Griffith, known mainly for the park and observatory bearing his name.

One of his poems about life in prison is republished below:

San Quentin’s Rugged Hill

by J. Wess Moore

There’s a rugged hill by Pacific’s tide, where the weeds do not grow tall;

a place of dread to the passers-by, when the evening’s shadows fall.

The laugh grows mute, their voices hush, they pass with quickened tread;

this little spot on this big earth, where sleep the convict dead.

There many lives that promised fair in boyhood’s early time,

lie stranded there, poor battered hulks wrecked by the waves of crime.

Those little mounds that dot the hill and the weeds that o’er them grow,

may cover hearts both kind and true, yet none but God may know.

The hope of many a household fair and many a mother’s pride,

lies here unwept, unsought, unknown, close by Pacific’s tide.

God grant that in their life somewhere, they did some deed of love,

to balance with their errors in thy book of life above.

God bless and keep those anxious hearts in near and far-off homes,

who wait in tender, patient love, for him who never comes.

They wait to hear that familiar step, that’s now forever still,

they’re watching for the boy that lies on Quentin’s rugged hill.

And while the breakers nearer creep, and ships sail on the bay,

that mother, sister, loyal wife, will wait and watch and pray.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Office of Public and Employee Communications

>> Read more about another Civil War soldier who served time at San Quentin and Folsom State Prison.

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.