California prison chaplains have long served the state to provide spiritual and moral guidance to those behind bars. They’ve officiated at funerals, helped plan education and baptized incarcerated congregants. Participation in religious observances is voluntary, but through the years chaplains have found themselves acting as librarian, counselor and therapist.

Who was the first prison chaplain?

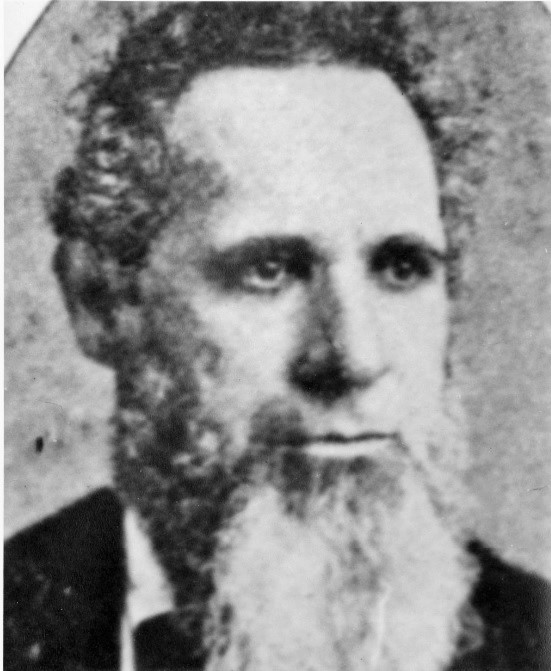

According to Kenneth Lamott’s book, “Chronicles of San Quentin,” William Hill was the first chaplain.

He was appointed Moral Instructor in 1881. After two years on the job, Hill was the first to be named Chaplain. He retired in 1889 due to deteriorating eyesight. In 1896, at 80 years old, he passed away.

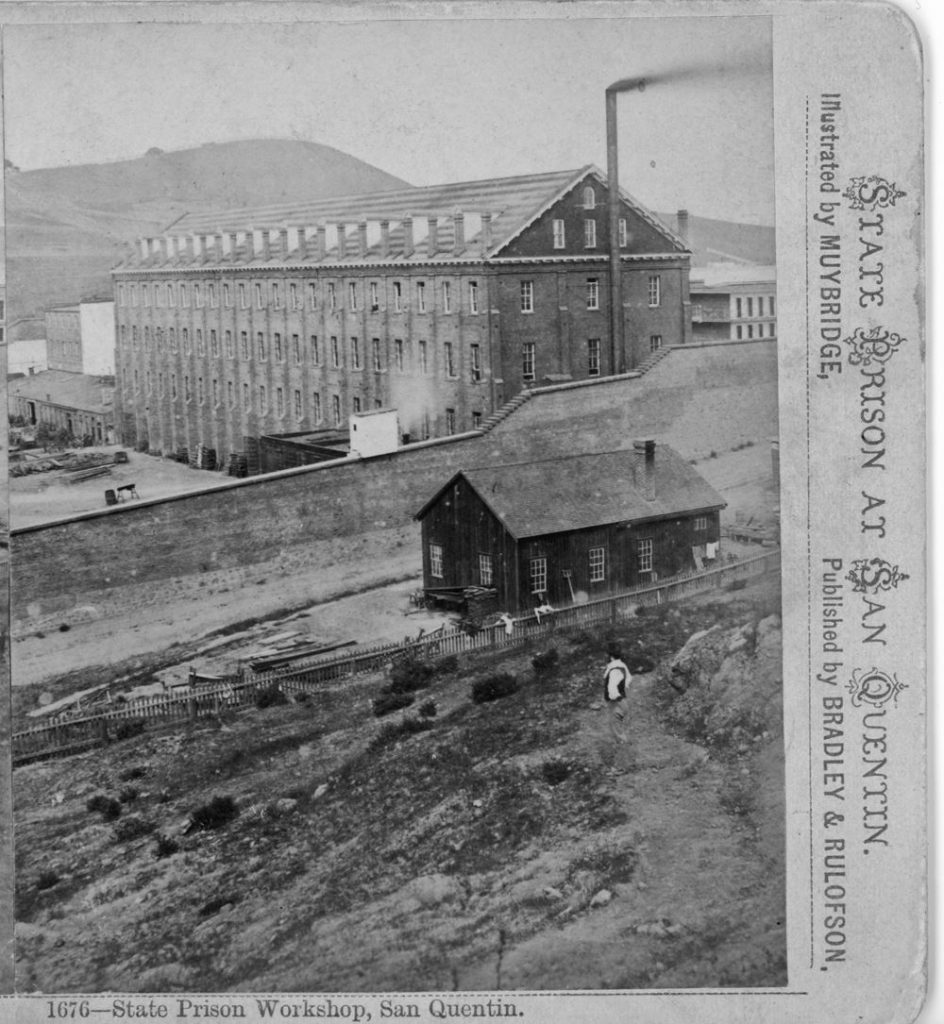

Prison chaplaincy goes back to 1858

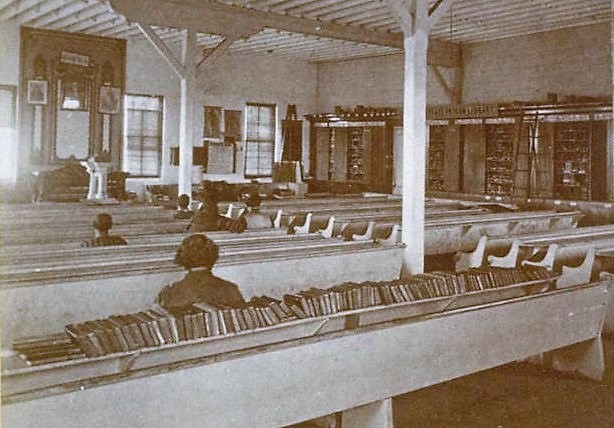

Regardless of the first official appointment, prison chaplaincy goes back to 1858, when Gov. Weller directed the San Quentin warden to provide for Sunday religious observances.

In December of that year, volunteer Rev. Gilbert began offering protestant services in the mess hall. The first Catholic Mass was held in March 1860, offered by Father Gallagher.

The varied religions practiced by inmates meant outside volunteer chaplains offered different religious services, sharing the duties.

William T. Lucky, the San Jose State Normal School principal, preached twice per month while two other Sundays were handled by Father Picardo and Rev. Rush.

The first moral instructor, C.C. Cummings, was appointed in 1870. He was followed by Rev. Hiram Cummings (no relation to C.C.). Hill was the next, appointed in 1881.

1860: State’s first Archbishop tends to San Quentin’s spiritual needs

In May 1860, Archbishop Joseph Sadoc Alemany preached in the San Quentin mess hall. Alemany returned to the prison often “to preside at the confirmation of convicts who had strayed from the Church in their misspent youth,” Lamott wrote.

Alemany had been in America since 1840, doing missionary work on the frontier in Ohio, Tennessee and Kentucky. In 1850, at just 36 years old, he was named Bishop of Monterey. In 1853, he transferred to San Francisco, becoming the state’s first Archbishop.

“When he began his work, there were but 21 adobe-missions scattered up and down the state, and not more than a dozen priests in all of California,” according to the Catholic Encyclopedia, published in 1913. Alemany died in 1888 at 74 years old.

State investigators believed an official chaplain would be beneficial for the rehabilitation of offenders.

“Your Committee recommend the appointment of a Chaplain, believing, if the proper person be appointed, such an officer would be of great benefit in carrying out reformatory measures. They also recommend an appropriation of $500 for the increase of the Prison Library, said amount to be expended in the purchase of suitable books by the Chaplain of the prison, under the supervision of the Directors,” according to the Report of the Joint Committee of the State Prison, 1868.

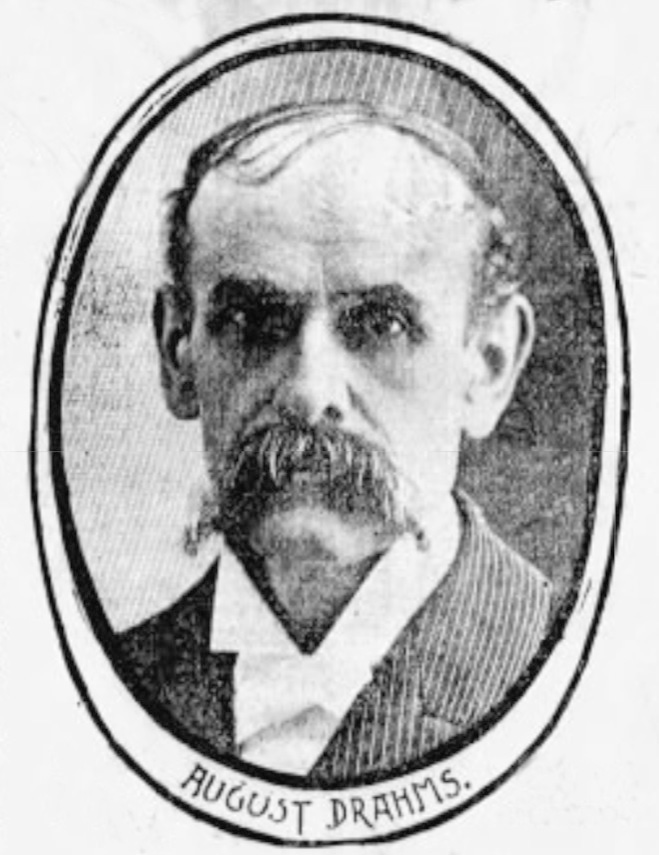

1900: August Drahms says rehabilitation is goal

“The chief value of incarceration should lie in the rational corrective measures (such as) educative facilities, psychological and industrial, that may … eventually result in moral and social rehabilitation,” San Quentin Chaplain August Drahms wrote in 1900. In 1909, Folsom Prison Chaplain William Lloyd echoed his remarks. Read more in this previous story.

1915: Michael Cahir counsels condemned man

Folsom Prison Chaplain Michael J. Cahir was by the side of 30-year-old condemned inmate Sam Raber, aka Sam Roberts, during his final days in 1915. Cahir was only 28 at the time.

Raber was sentenced to death for the July 8, 1913, murder of Cherry de St. Maurice, the well known owner of Sacramento’s Cherry Club.

Raber and his girlfriend Cleo Sterling conspired to rob St. Maurice. Sterling was one of the club’s prostitutes.

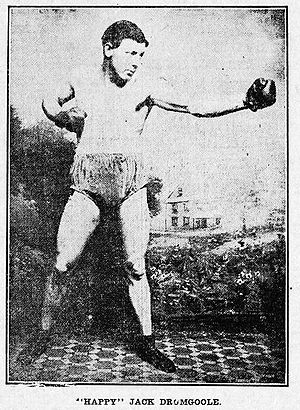

Needing help, Raber enlisted his friend Jack Drumgoole, a professional boxer. In the dark of night, the men entered St. Maurice’s room. Startled by the intruders, she lunged forward, landing in Drumgoole’s path.

“Drumgoole grasped the woman by the throat to keep her quiet,” according to the Sacramento Star, Jan. 15, 1915.

Sterling was acquitted. Meanwhile, Drumgoole admitted strangling St. Maurice, earning a life sentence at San Quentin.

“Drumgoole and Raber said they did not intend to murder the woman,” the newspaper reported. “Drumgoole’s confession (claims) Raber worked for more than five minutes (to) revive her.”

Chaplain Cahir spent several days with Raber.

“I became greatly attached to him and feel sure that if he had been given a proper start in life, he would have been a good man,” Cahir said.

Raber was hanged at 10:01 a.m. Jan. 15, 1915. Standing nearby, Cahir prayed aloud.

In 1920, 32-year-old Drumgoole died at San Quentin. News reports claim he fell victim to tuberculosis.

Cahir was also 32 when he passed away “from heart trouble,” according to the San Francisco Examiner, Feb. 15, 1919.

1920: O.C. Lazure promotes rehabilitation

During the 33rd annual convention of religious leaders, San Quentin Chaplain Oliver C. Lazure said the prison was “the great social clearing house for the state of California,” according to the Fresno Morning Republican, June 29, 1920.

“Men are not bettered or materially improved simply by confinement, there must be something built in if they would go out of the institution fit to return to society,” he told the gathering.

He urged religious leaders to get involved with the prison system and “to link the young people of the state with the great reconstructive and regenerative movement now in progress.”

Speaking in Los Angeles, Lazure urged employers and the public to be more understanding of people who served time in prison.

“It is up to you on the outside of the prisons to give them a square deal. It is because they have a cold reception when released that men who have been to prison become discouraged and again commit crimes and are sent back to us at San Quentin,” he told a gathering, according to the Los Angeles Times, Oct. 30, 1921.

1931: P.J. Cronin believes human nature is ‘wholesome’

Folsom Prison Chaplain Patrick “P.J.” Cronin openly discussed his views on crime, human nature and taking responsibility for one’s own actions.

Despite his prison work, he still believed in the “innate wholesomeness of human nature,” reported the United Press (UP), Dec. 29, 1931.

“Society is not to blame for crime, although it is a social phenomenon,” he told the UP.

He said two of the most glaring causes of crime “today are too much wealth as contrasted with too much poverty.”

Even though the country was in a deep economic depression, he said that was not the cause of increased crime.

“Crime has much of its root in the false valuation given to mere possession of wealth,” he said, optimistically predicting the inherent good nature of humans would prevail.

1932: Larry Newgent says focus on children early

For more than a dozen years, Rev. Larry Newgent served as the chaplain at San Quentin. After his retirement, he discussed his views on the causes of crime and the nature of those who are incarcerated.

“Rev. Newgent accompanied 45 (condemned inmates) on the death march to the gallows. He studied criminals closely during his grim career,” reported the UP, July 21, 1932.

He said, “It’s bad company, thirst for thrills, the desire to be tough, that starts them (on the criminal path). They become hardened and calloused. The time to do something (to help them) is when they are youngsters.”

He said “speakeasies” and “taxi-dances” introduced them to crime. Speakeasies were clubs and bars operating underground during Prohibition, when alcohol production and consumption were illegal in the 1920s and 1930s. Taxi dance halls featured a dance floor and music, supplied by the hall, with women being paid to dance with male patrons. The men purchased dance tickets for 10 cents each.

1942: First full-time Catholic chaplain appointed at Folsom

“For the first time in the history of Folsom prison, a Catholic chaplain has been named full time spiritual adviser and religious educator to the prisoners. He is Father William O’Toole of Sacramento. His appointment was approved by the state board of prison directors upon recommendation of Warden Clyde Plummer. He has been acting as part-time chaplain at the prison since 1941,” reported the United Press, July 16, 1942.

1943: Emil Marcussen, 85, retires after 22 years at Folsom

“Colonel Emil Marcussen of the Salvation Army conducted his farewell service for the inmates at Folsom Prison last Sunday. He plans to retire from active service immediately and will make his permanent home in Berkeley,” reported the Folsom Telegraph, Nov. 5, 1943.

Born in Copenhagen, Denmark, in 1858, the 85-year-old chaplain was ready for a change. He had served the inmates at Folsom Prison for 22 years, assuming his prison post in March 1921.

“His assignments have been mostly in the prison service department and his work has taken him over most of the world,” the paper reported. “He is one of two persons to whom the king of Denmark has awarded (a medal) for humanitarian service.”

He saw four wardens cycle through Folsom Prison during his tenure.

1965: San Quentin Chaplain asks Sinatra to perform

When a chaplain at San Quentin reached out to Frank Sinatra to perform for inmates, the famous entertainer accepted. He also brought the entire Count Basie Orchestra along for the show.

“At this point in his affluent career, he responds more quickly to a request to perform at a benefit concert than an opportunity to make money,” CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite reported in 1965.

“I enjoy being with the public almost under any circumstance regardless of where it is or why,” Sinatra said. “So I do my utmost to fulfill that responsibility as a performer and a man of public life.”

Read more about chaplains

- In the 1860s, chaplains brought Thanksgiving inside the prisons, offering special religious services and meals. Read the earlier story.

- In 2018, Inside CDCR visited Intermountain Conservation Camp and interviewed two volunteers who brought church services to the inmates. Read the story.

- At CSP-Solano, chaplains facilitate the Asian and Pacific Islander Cultural Group. Watch the Inside CDCR video.

- Learn more about CDCR’s chaplains.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.