Meet some of the first female correctional officers

The first female correctional officers maintained public safety while overcoming challenges from leaders, coworkers and incarcerated.

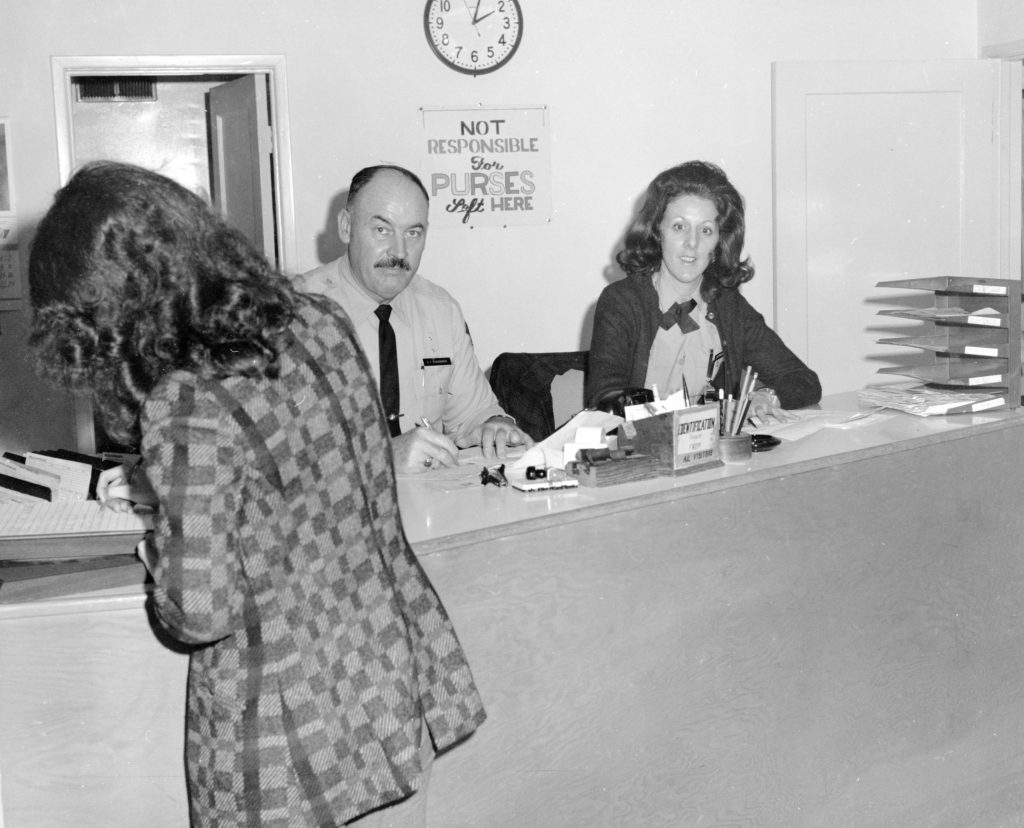

Before the 1970s, prison jobs for women were limited to desks, phones, filing and typing. Today, thousands of women fill the ranks of custody staff at every level including officers, wardens and executives.

When the California state prison system started, there was one floating institution – the Waban, a rickety ship anchored at Point San Quentin.

Going ashore during the day, those incarcerated on the ship built the first state prison at San Quentin.

Before 1944, correctional officers were classified as guards, and all of them were men. It would take more than a century for the first females to take up correctional officer duties. Those women opened career doors for others to follow.

Early female correctional officers said they faced hostile work environments from the incarcerated as well as from fellow officers. There was a lot of pressure on those first female officers, with many saying they needed to work twice as hard to prove themselves.

Some officers and executive staff offered support as the department went through the same changes as the rest of society.

Technically, there were female guards at San Quentin (SQ) almost since the beginning of the institution. They were used to supervise the female inmates originally housed at SQ before they were transferred to Tehachapi in 1932. However, back then they were not used to supervise the male inmate population.

Dorothy ‘Dolly’ Taylor was first female officer

According to the San Quentin Alumni group, the first modern female correctional officer was a clerk who found herself promoted to officer to supervise a condemned female.

While waiting on Death Row at San Quentin, Barbara “Bloody Babs” Graham needed to be supervised by a female correctional officer.

“If you want to go way back, Dorothy ‘Dolly’ Taylor was the first CO at San Quentin. She was clerical when Barbara Graham arrived at SQ death row from California Institution for Women in 1955,” according to Dick Nelson, retired SQ associate warden. “Dolly was promoted to CO to (supervise) her. I believe Graham was there for six weeks before she was executed (because she got) at least one stay. After the execution, Dorothy demoted back to a clerical position and worked the mail room for many years. She was again promoted to CO in the 1970s and retired as a CO.”

On June 3, 1955, Graham became the third female inmate to be executed in the gas chamber. Her trial sparked media interest and the 1958 movie “I Want to Live” starring Susan Hayward, earning Hayward an Oscar.

Graham was convicted of the 1953 murder of 64-year-old Mabel Monahan. She and two accomplices were in search of a rumored stash of money in the woman’s home, but they found nothing of value. The two male accomplices were also executed.

The first woman executed was Juanita “The Duchess” Spinelli in November 1941. The second was Louise Peete in April 1947.

Linda Clarke was first female officer at Soledad

In 1971, Linda Clarke was 26 years old when she became the first female officer to work at the Correctional Training Facility in Soledad, according to CTF Associate Warden Jeff Soares in his book, “History of Soledad.”

According to Soares, she was not given the title of Correctional Officer but was classified, as all the other women in her position, as “Women Correctional Supervisors,” for which there were several levels.

“There was significant discrimination against all the women and they were often told they would not be given any promotion when they had applied, because they were women,” Soares writes.

Clarke recounted how it was tough at first and promotions weren’t in the cards.

“According to Clarke, when she had put in for a promotion, she was told to wait in a room to be called for her interview. She waited the entire day before someone came back and told her the interviews were over,” Soares writes.

Clarke worked as a Correctional Officer from 1971 until 1978. From 1981 to 1987, she returned to CTF as a training manager.

Gov. Pete Wilson appointed her as CTF’s first female warden in March 1995. There were 10 other female wardens serving in the state at the time, according to Soares.

“The staff, I think, was very pleased to welcome back one of their own. I think they’re very proud of that. It will be even more of a challenge not to disappoint them,” Warden Clarke told the Salinas Californian at the time.

Karon Larson was one of four of CTF’s first female officers

According to the Old Guard Foundation, a group of retired Correctional employees, Karon Larson and three others were the “first female officers assigned to a California men’s prison” in 1972 at the Correctional Training Facility in Soledad.

She began her career with the department in 1962 as a clerk typist. In 1971, she became a Correctional Supervisor at the California Institution for Women.

She transferred to San Quentin in 1981, where she worked the Security Housing Units (SHU) and Condemned Row. In 1984, she transferred to Folsom State Prison, working in the SHU, Appeals and General Population.

She retired in 1996 with more than 32 years at the department.

Ilene Williams promoted through the ranks

Ilene Williams was looking for a challenge when she went to work at San Quentin in 1972. Already been with the department for five years, including as a correctional counselor at California Rehabilitation Center, she said a lot was riding on the success of the first female officers.

“I interviewed at San Quentin in early 1970 (and got) the job. Shortly after I interviewed, the George Jackson riot occurred,” she explained in 2004. “The plan to bring females into San Quentin as Correctional Officers was delayed for one year.”

While women worked custody positions before 1972, it was a different classification.

“It was not a matter of women being barred from working at San Quentin. (The prison) hired Correctional Officers (but) we were (known as) Women Correctional Supervisors I, II and III, which were designated positions for female institutions, not male prisons,” she wrote. “For females, it meant they would be assigned to San Quentin only and in SQ Visiting Program only (so) this new venture (could) be evaluated.”

Since women didn’t have official uniforms, she helped design them.

“We wore regular clothes until we got the uniforms,” she wrote.

She also became the first female officer to wear one.

A year later, she promoted to correctional sergeant, transferring to California Institution for Women.

Over the years, she worked her way up the ranks, promoting to Lieutenant, Night Watch Commander and Correctional Counselor at California Institution for Men. She also worked at Headquarters in Sacramento.

In 1991, Director of Corrections James Gomez recognized her efforts.

“You had the distinction of being one of the first women Correctional Officers in a men’s prison,” he wrote. “You paved the way for other women employees in the department.”

After 27 years of service, she retired in 1994 as Chief Deputy Warden at CSP-Corcoran.

Joyce Zink experienced hostility early in career

Alongside Ilene Williams, Joyce Zink was among the first female Correctional Officers at San Quentin in 1972.

Zink started her career the year before at the California Institution for Women, transferring to San Quentin to supervise visiting. She said she felt isolated in the position and thought a more challenging post might be had at Folsom.

“She transferred to the visiting room there in 1973, once again as the first woman to hold such a position,” according to an article in Correction News, published in 2002. “The reception she got wasn’t so warm.”

Zink recalled being ignored when she offered morning greetings to her fellow officers. She was later transferred to a gun tower far from the main yard.

“I knew it wasn’t going to be overnight that I got to go inside (inmate housing),” she said in the article.

Eventually she was given a position in the largest housing unit.

“I thought, ‘Oh good, I actually get to go inside,’” she said.

In 1976, she was promoted to Sergeant, transferring to the Correctional Training Facility at Soledad and later to the California Institution for Men. In the 1980s, she rose to the rank of Lieutenant and later to Captain, after transferring back to Folsom following brief stints at Headquarters and San Quentin.

During her career she served as a Program Administrator for the administrative segregation unit at California State Prison, Sacramento, and ran housing units at Folsom State Prison and CSP-Sacramento. She retired as a Captain from Folsom State Prison in 2000.

“I always wanted to do something that’s a little bit different, not to be a rebel, but do something that would make a difference in society,” she said. “I wasn’t trying to make a name for myself (and) was more adventurous, I guess.”

Wilma Schneider fought battles on many fronts

Wilma Schneider was hired in 1973 and newspapers around the world picked up the story.

In March 1973, the Associated Press (AP) penned a piece on Schneider, declaring her the “first woman on San Quentin’s correctional officer staff in the history of the prison.”

“I can’t help but think that if I don’t succeed, I’m going to ruin it for all women,” Schneider told the AP.

Schneider started working at San Quentin after three years of experience as a group supervisor at the California Youth Authority’s Los Guilicos School for Boys and Girls.

There would be no special treatment, explained Associate Warden James Park.

“She qualified as a Correctional Officer. That means she will be expected to handle all the assignments a male officer does, including gun tower and gun rail duty and cell block supervision,” he told the AP.

Schneider met resistance from other officers, incarcerated men and media outlets.

According to a United Press International (UPI) news report in March 1973, Larrance Hand sued to have Schneider and fellow officer Bonnie Briggs removed from the prison. Hand, who was incarcerated, said their presence made him “feel romantic but prison rules barred him from showing this emotion.” His lawsuit was dismissed.

She left the job in 1975. Schneider, who today is known as Wendy Woods, authored a book chronicling her San Quentin experiences.

Marie Brooks was first female officer at CMF

In 1973, Marie Brooks became the first female correctional officer at the California Medical Facility, according to the Vacaville Reporter.

“She was straight-up business,” said fellow Officer Joyce Thompson in a 2005 Vacaville Reporter article. Thompson started in 1978 and trained under Brooks. “She handled inmates like you tied your shoes.”

Thompson said it was difficult for Brooks.

“First, she was a woman, and she was a black woman,” Thompson said. “They were not happy she was here. Male officers believed a prison was no place for a woman.”

According to Theresa Brooks, Marie’s daughter, the first academy for female correctional officers to graduate from the Correctional Training Facility at Soledad (April 30, 1973-June 1, 1973) included Lillian Bledsoe, Marie Brooks, Geraldine Copeland, Betty Gosston, Leslie B. Johnson, Dorothy Killian, Trella F. Robertson and Catherine Seward.

Learn more

- Meet Jessie Whalen, SQ Women’s Ward matron.

- In 1922, the matron oversaw these incarcerated women.

- Explore how the suffrage movement expanded correctional job opportunities for women.

- Women take on leadership roles.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Historical photos compiled by Eric Owens, CDCR Staff Photographer

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.