Since the early days of the prison, incarcerated women have been supervised by matrons. In honor of Women’s History Month, Inside CDCR takes a closer look at some of the women working in a male-dominated environment. Their efforts laid the foundation for women to follow a century later.

In 1868, despite having incarcerated women, there was no female matron.

“There are but three females confined in the prison,” reported the Daily Alta California, Aug. 9, 1868. “They occupy apartments over the officers’ quarters in the yard, and are kept strictly secluded. They are not allowed to leave the building during weekdays. On Sundays, while the (men) are attending (church), the females are permitted a few hours open air exercise. The diet (for the women is) superior, furnished from the table of the officers. One woman has an infant, (a little) over a year old.”

San Quentin’s first matron

Seeing the need for more organization, the Board of State Prison Directors took action.

Prison officials will “create the position of Matron at San Quentin,” reported the Daily Alta California, Jan. 23, 1885. “The duties of the Matron, to be appointed by Warden Shirley, will be to assume guardianship of the female prisoners. Her salary will be $50 a month and board. The females now confined in San Quentin number 15 in all.”

In 1885, one of the prison reports mentioned improvements at the Women’s Department run by matron, Mrs. Lancaster.

Construction plans included “a two-story brick building for the resident physician and (an) addition to the female department (costing) $6,962. The latter improvement was very necessary, and has resulted most satisfactorily to the unfortunate women confined here. The female department (is overseen by a) matron, under whose supervision the (women) are employed at labor,” the report stated.

Establishing the matron role

In 1888, a new warden appointed a new matron.

“General McComb last week took full charge of the San Quentin Prison,” reported the Sausalito News, Jan. 5, 1888. “Warden McComb (appointed as) matron of the female prison, Mrs. Mary Kane.”

While the matrons oversaw females, the job was still dangerous.

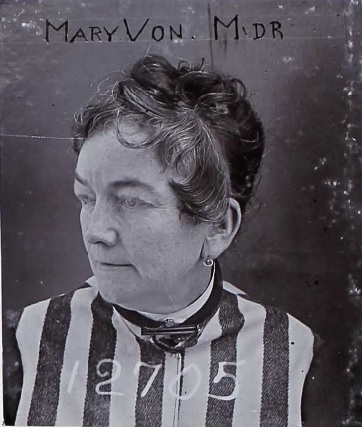

“Mary Von, the murderess, who is now serving a life sentence at San Quentin for the killing of J.W. Bishop, attempted to murder Mary Kane, the matron of the female department of the prison. Mary Von sprang upon the matron and dealt her heavy blows with a piece of iron,” reported the Pacific Rural Press, July 21, 1888.

In 1891, Warden Hale appointed C.E. Dutcher to the post. The prison board of directors also “adopted a new series of rules for the government of the prison,” according to the Daily Alta California, March 28, 1891.

The next matron was Belle Van Doren, appointed in 1895. She held the post until 1909.

“After holding the responsible position of matron of San Quentin prison for the past 14 years and at the urgent request of her son, Mrs. Belle Van Doren has tendered her resignation and will retire to private life and live in Tiburon with her son, Wilbur Van Doren. She has held the position longer than any other matron, retaining it through several administrations more on account of her ability rather than political influence,” reported the Sausalito News, Oct. 9, 1909.

She passed away in 1929 at age 75.

Turning a page in the female department

Van Doren’s replacement was Genevieve Smith. She earned $840 per year while her husband Richard earned $780 per year as a guard.

In 1912, Florence Roberts, a missionary, published “Fifteen Years with the Outcast.” Some of the book focused on San Quentin’s incarcerated female and their matron.

“How do I praise God that he put it into the heart and mind of the present matron, Mrs. Genevieve Gardner-Smith, to appeal to kindhearted Warden Hoyle and the board of prison directors for a special concession in behalf of all the well-behaved women prisoners. She asked for a monthly holiday, to consist of a two-and-a-half hours’ walk within the grounds … so that these poor women might briefly feast to the heart’s content on the lovely landscape and view of San Francisco’s unsurpassable bay. (They now offer the women) a Sunday walk on the hills once a month,” she wrote.

Well-liked matron

The inmates were appreciative of Smith’s efforts. When she reached her first anniversary in her position, the women banded together to honor her.

“To this day (the women) believe the affair to have been a complete surprise, though (the matron) was aware of their preparations from the beginning. The day broke warm and beautiful. Immediately after dinner, Matron Smith was escorted to a seat of honor in the yard and the program was opened by an excellent address of women by (an inmate),” Roberts wrote.

Smith held onto the post until 1914.

“San Quentin to have new matron,” claimed the headline of the Sacramento Union, Feb. 20, 1914. “Genevieve Smith, for the last (several) years matron of the women’s department at the state prison, was (replaced) by Warden James A. Johnston (by appointing) Jesse Whalen, former matron of the Southern California state hospital.”

Read more about Whalen’s focus on mental health.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Historical photos compiled by Eric Owens, CDCR Staff Photographer

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.