In late 1800s, mental health issues were seen as weakness

After witnessing the horrors of the Civil War, battling crime as a police officer and finally serving as the San Quentin executioner, Amos Lunt saw his physical and mental health fade.

A century ago, little was known about trauma’s impact on mental health. This is the story of a staff member who, if diagnosed today, would have had access to a range of mental health services and peer support.

(Learn more on the Employee Wellness website.)

(Editor’s note: This story originally published on Inside CDCR in 2018, but has been updated and revised.)

Lunt was Civil War veteran, lawman

Born in Massachusetts in 1846, Lunt joined the military when he turned 18 in early 1864. The country was embroiled in a bloody Civil War, pitting the Union against secessionist forces.

Having served in the Civil War with the 3rd Infantry, Massachusetts regiment, Lunt was no stranger to the darker nature of humankind. He served for nearly six months when he was mustered out of service.

In the 1870s and 1880s, he served as a Santa Cruz police officer as well as Chief of Police.

Executions move from counties to state prisons

A new state law barred executions from being carried out by county jails, centralizing them in state prisons.

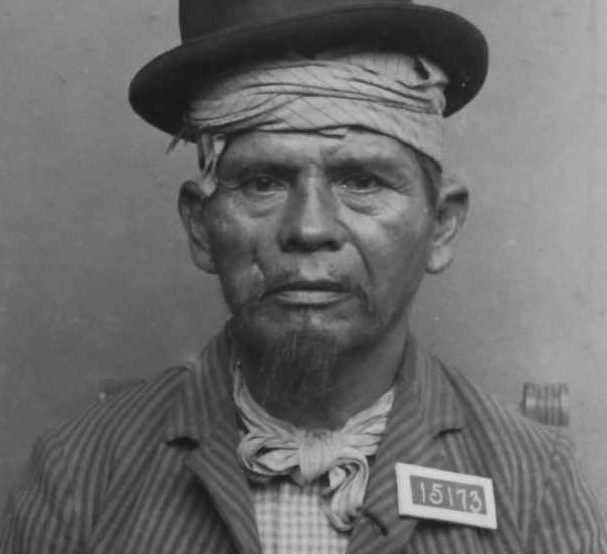

The first execution carried out under the new law was that of Jose Gabriel, prison number 15173.

The 60-year-old Gabriel, a wood chopper working for a couple at Otay in San Diego County, was digging a cistern for water storage.

According to newspaper accounts, he became angry and quit the job, demanding immediate payment. In the end, he murdered his employers and almost killed their nephew. Gabriel was received at San Quentin on December 19, 1892.

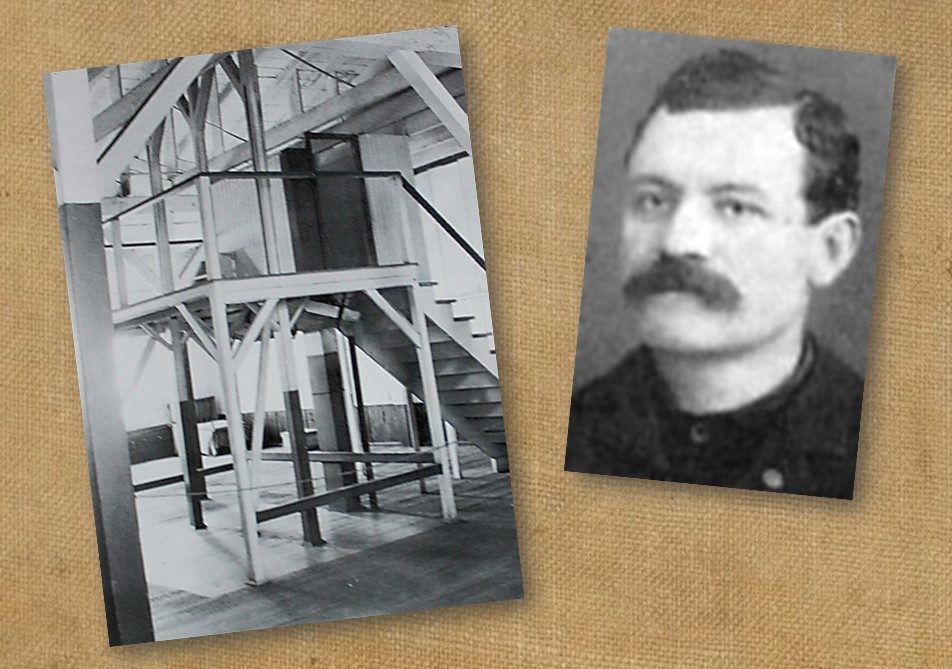

For the first official state execution, Warden Hale was assisted by prison employee John McKenzie and three guards: Williams, Ferguson, and Moons.

While the procedure appeared to go smoothly, Hale believed the process could be improved. Since the duties of executioner were the sole responsibility of the warden, Hale created the Chief Deputy Warden position in 1894, appointing Lunt to be the first.

Lunt assumes grim San Quentin duties

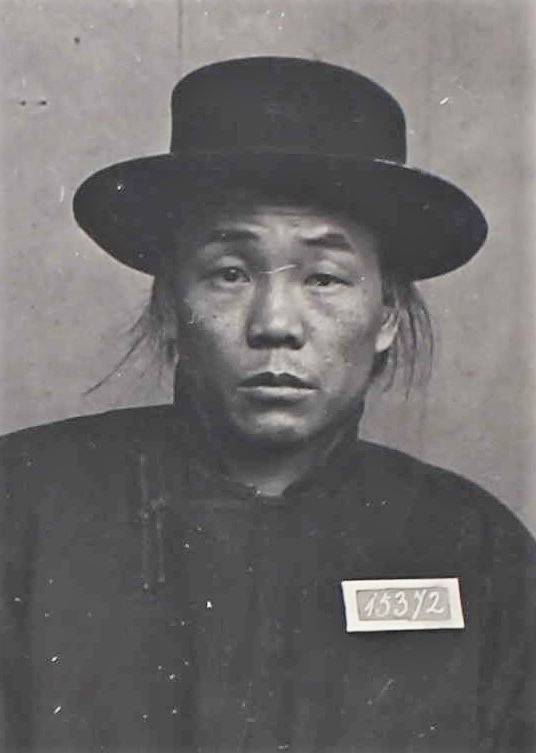

The second execution at San Quentin, and the first for Lunt, was Lee Sing, 15372. He was released to the sheriff while on appeal at the state supreme court. His appeal denied, Sing was resentenced to death, and returned to San Quentin with the new number 15692.

Sing, a cigar maker, was convicted of first-degree murder in the shooting death of Ah Kee.

On the morning of February 2, 1894, Captain Edgar and Warden Hale entered Sing’s cell and read the death warrant. “All right. I am ready,” Sing told them.

At 10 a.m., 15 people, including members of the press, were escorted to the execution chamber.

At 10:35 a.m., Sing was walked to the gallows by the warden, Chaplain August Drahms, Lunt and three guards.

“They ascended the steps leading to the scaffold, where the leg and arm straps were adjusted,” reported the San Francisco Call, February 3, 1894. “Lunt placed the black cap and rope around the neck (while) Drahms held the hand of the the condemned. The signal was given and the trap was sprung.”

At 10:55 a.m., Sing was pronounced dead.

Infamous Belfry Murderer hanged by Lunt

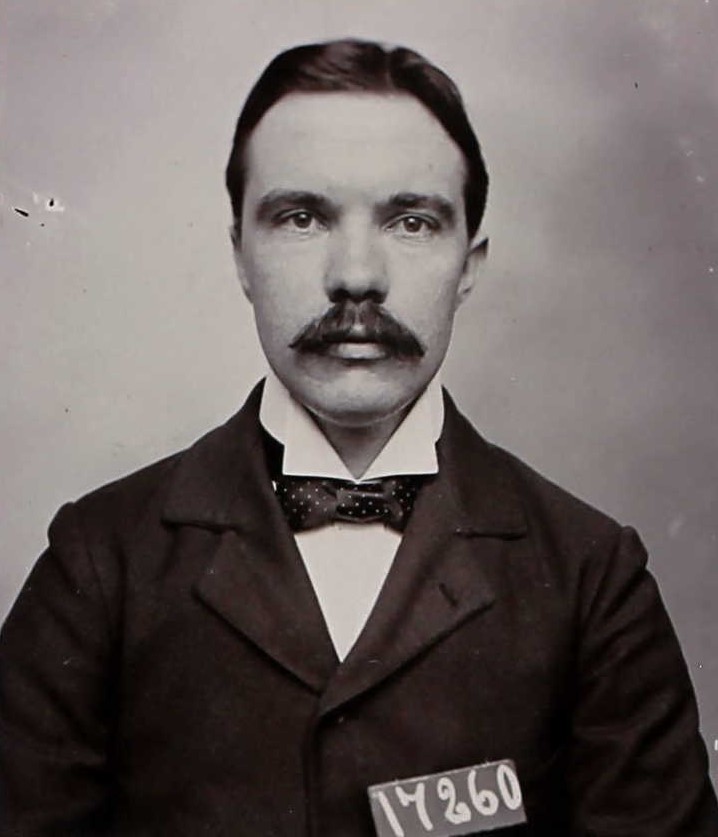

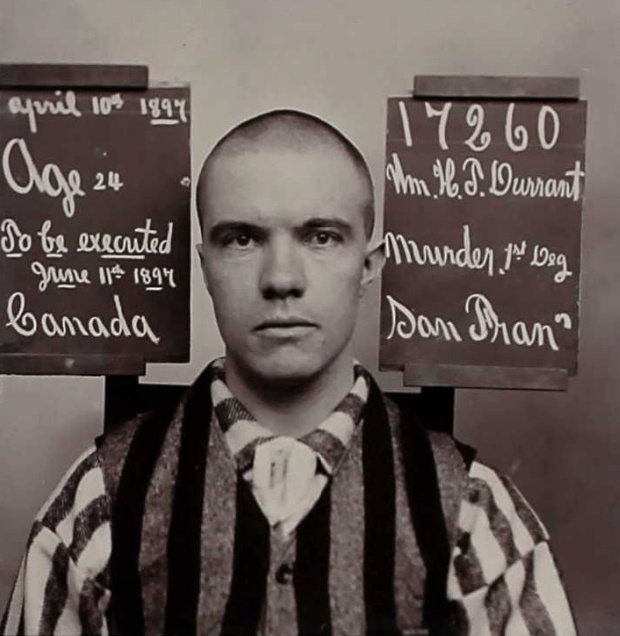

When Theodore Durrant was convicted of murdering two women and hiding their bodies in a church, Lunt didn’t hold back his feelings about the young medical student. The press dubbed Durrant the “Demon of the Belfry” and the “Belfry Murderer” because he hid one of his victims in the church belfry.

“I believe Durrant murdered both of those innocent girls in cold blood,” Lunt said, according to the San Francisco Call, May 14, 1897. “Hanging is too good for him.”

Durrant was executed January 8, 1898.

San Quentin executions of Miller, Clark push Lunt to breaking point

John Miller had a physical deformity affecting his neck, spine and shoulders. His crime was the result of spurned love, stalking, and the intervention of a citizen. After his affections were rebuffed by a woman, Miller threatened to kill her. A few days later, he returned, chasing her down side streets while brandishing a pistol. Another man heard the woman screaming and rushed to stop Miller. Instead, the man was shot dead and Miller was convicted of his murder.

As was his practice, Lunt reviewed commitment papers and reception documents, including weight and size. In light of Miller’s unique physical characteristics, Lunt proposed giving the man a shorter “drop.” On October 15, 1898, his advice went unheeded and, in front of witnesses and members of the press, the hanging ended in blood and near decapitation. According to various accounts, the entire episode left Lunt very shaken.

George Clark, Lunt’s final execution, was held only a week following Miller.

Clark was convicted of murdering a man so he could be with the victim’s wife. The murder victim was his brother. While awaiting execution, San Quentin Chaplain Drahms spent time with the condemned man.

On October 21, 1898, Clark met with the chaplain to pray and sing hymns.

“They passed (the time) until 10:25, (when) Warden Hale interrupted the devotions. (Clark) waived the reading of the death warrant (and) guards fastened straps to his wrists and ankles. (Then they walked to the) gallows in the next room,” according to newspaper accounts.

The trap dropped at 10:32 a.m. Doctors pronounced Clark deceased 10 minutes later.

Lunt’s final days filled with struggles

Lunt oversaw 20 executions, personally placing the noose around the necks of 19. The duties, combined with his years of dealing with traumatic events, took their toll.

He began exhibiting signs of extreme stress, resulting in his reassignment to a guard post.

Frank Arbogast was assigned as Lunt’s replacement, according to the San Francisco Call, October 23, 1899.

“They are after me,” Lunt told Arbogast. “There are several under the bed now. A convict is assisting them (therefore) it’s only a matter of time until they get me.”

For five days, Lunt refused to light a fire or the lamps in his quarters. He barely ate and rarely slept for fear “the specters” would attack him when off his guard.

In the end, Judge Bahrs “reluctantly signed the order of commitment,” placing Lunt in an asylum in late 1899.

“Months before his incarceration in the asylum, he complained he was haunted by (those) he sent into eternity. He had been confined to the (asylum) for more than a year,” reported the Santa Cruz Sentinel, September 23, 1901. “He was a physical and mental wreck.”

Lunt was 55 years old when he passed away September 19, 1901.

By Don Chaddock, Inside CDCR editor

Additional resources and links

A recently published book is now available at online retailers: “American Hangman: A Biography of Amos Lunt, the Executioner of San Quentin,” by Tobin T. Buhk.

Additional resource: There is also a non-CDCR video discussing Lunt and his brief time at Napa.

Did you know? Warden Hale and Captain Edgar foiled a deadly plot in 1891.

Learn more about Chaplain August Drahms and the birth of rehabilitation.

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.