In honor of National Law Enforcement Appreciation Day, Inside CDCR takes a closer look at the history of custody staff and how their roles have evolved since 1851.

From prison ships to stone buildings

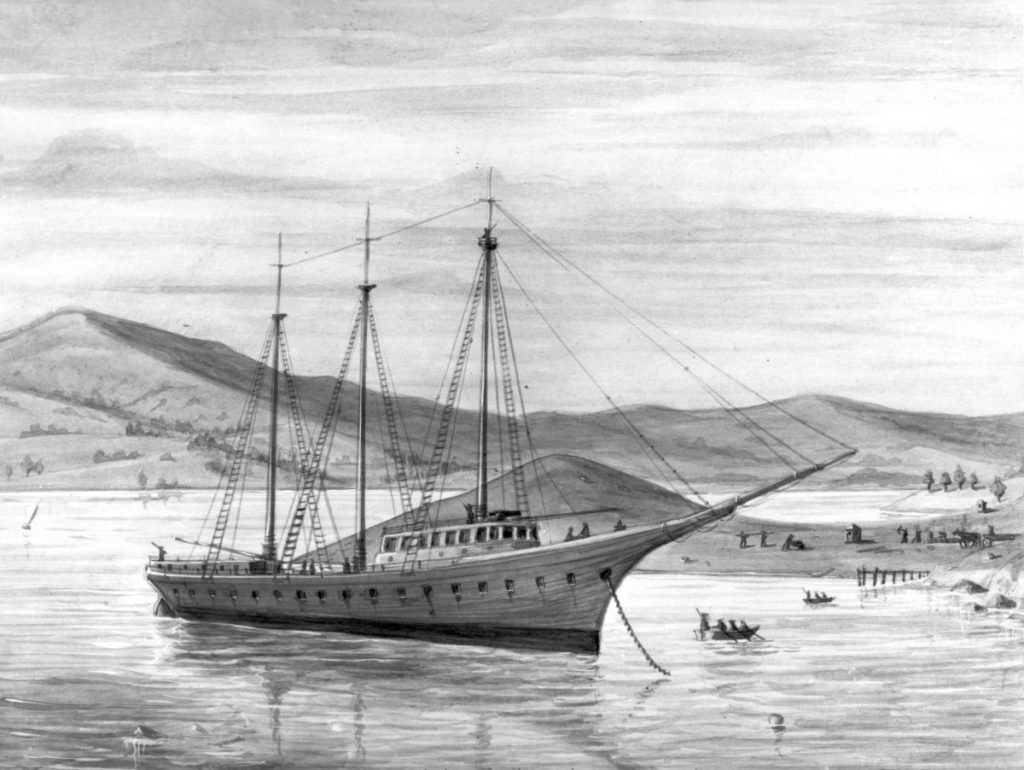

Beginning with the Waban in 1851, custody staff have filled many roles: guard, officer, counselor and worksite supervisor. Before the Waban, incarcerated people were briefly held on the Sacramento leased ship the Strafford. When the lease was canceled in 1850, Sacramento acquired the La Grange. Meanwhile, San Francisco incarcerated people onboard the Euphemia.

A local newspaper described conditions on the La Grange.

“The prison brig is a decidedly pleasant place, and the prisoners have full view of the business on the levee, the steamers as they ply up and down the river, and are no way restrained of liberty, except that they wear heavy chains, which is doubtless against their will. In addition, (they) have not the liberty to go on shore when they fancy,” reported the Sacramento Transcript, April 5, 1851.

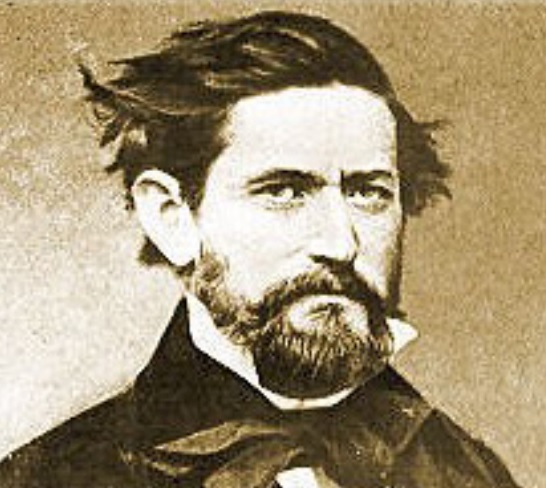

Sheriff acquires first state prison ship

The Waban was purchased by San Francisco Sheriff John Coffee “Jack” Hays, a former Texas Ranger and military veteran of the Mexican American War. He, like many others, arrived in California during the 1849 Gold Rush.

But first, the ship needed to be converted to a prison. For that, Sheriff Hays needed lumber. The San Francisco Maritime Museum has a receipt for 5,550 feet of redwood, used to create cells on the ship.

In December 1851, he received the first 40 incarcerated people and sailed to Angel Island.

(Read the story about ships serving as the state’s first prisons.)

Ships were regularly used

Other ships were acquired and used to house incarcerated work crews at island quarries. While living on the ships, workers built the first cells. Three years later, a reporter visited the ships and the prison.

At the time, there were 150 incarcerated workers quarrying stone at Marin Island. Lt. Gray was the crew superintendent who also oversaw 14 guards.

“The guards are composed of picked men, and are commanded by Capt. Asa Estes, an old mountaineer,” reported the Daily Alta California, Dec. 1, 1854. “The prison is situated upon a hill, overlooking the bay and is a solid, beautiful piece of masonry.”

Estes had worked with the U.S. military as a guide, so had experience with strict rules. He was one of many veterans recruited by prison contractor James Estelle.

(Read the original Inside CDCR story on Asa Estes.)

A history of recruiting former soldiers, police as custody staff

When Estelle took over the prison contract, he sought to recruit former military men, hoping it would bring order to the prison. Critical newspaper accounts, negative annual reports and escapes required operational changes.

In addition to Estes, he recruited William “Bill” Byrnes, a former California and Texas Ranger as well as a veteran of the Mexican American War. He was hired as the Captain of the Mounted Unit, according to prison records.

Today, military veterans are still recruited to serve as correctional officers at CDCR.

Law enforcement officers were also recruited to work in custody roles at the state prisons.

H.C. Herrill was a constable and sheriff’s deputy in Placer and Sacramento counties when he was appointed in 1891 to guard positions at San Quentin and later at Folsom State Prison. Herrill was known for his community involvement, much like staff today.

(Read the original story on H.C. Herrill’s career.)

In 1894, Civil War veteran and former police chief Amos Lunt was hired as the first executioner at San Quentin.

(Read the story on Amos Lunt.)

Dangerous job for those protecting the state

Charles Jolly was a guard at Folsom State Prison from 1893 until 1926. During his career, he was stabbed, had his throat slashed and helped track down escapees.

Ben Merritt, a former sheriff, also survived attacks, tracked down an escapee and when he believed someone needed a helping hand, he advocated for their pardon. He worked at San Quentin and Folsom State Prison, beginning in 1895.

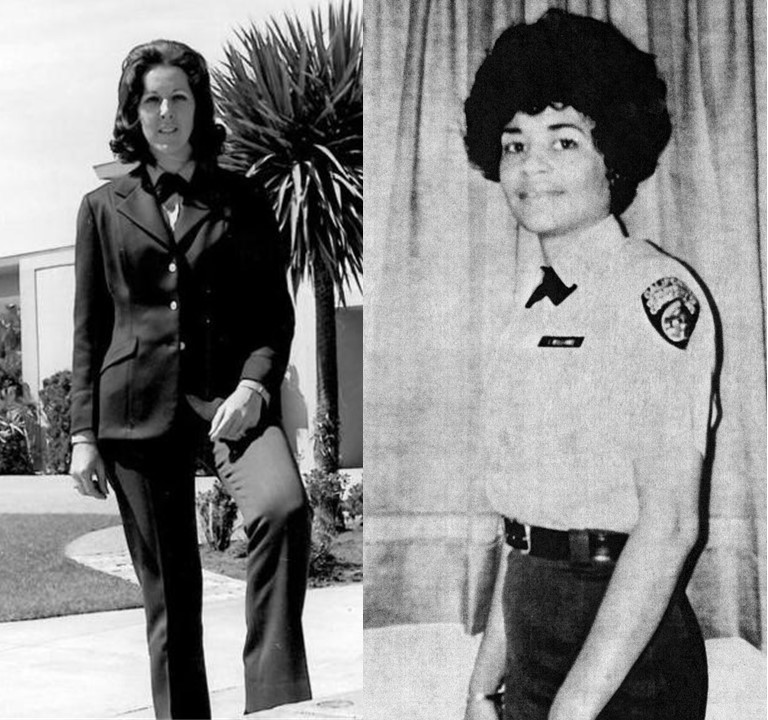

Females have worked at the department since the early days but were finally appointed to correctional officer positions in the 1970s.

(Their struggles are detailed in this earlier story.)

Over the years, the roles of custody staff have evolved. When interviewing longtime Correctional Officer Mike Begley in 2017, a few months before his retirement, he said one of the biggest changes he saw was related to rehabilitative programming. Begley had worked what he calls The Row since 1991.

“The prison has gone from a custody side more to an emphasis on the medical. That’s the biggest change. Also, we went from Level IV to reception,” he said. “Also, there are a lot of different (rehabilitation) programs now. Before, everything was contained to East Block for condemned inmates. You didn’t really take them out for anything else.”

(Read the original award-winning 2002 story.)

(Read the the 2017 follow-up.)

Related content

Learn more about California prison history.

Follow CDCR on YouTube, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter). Listen to the CDCR Unlocked podcast.